'When it comes to India-Pakistan relations, seminal moments of progress invariably bring out saboteurs of peace -- whether we're talking about fresh provocations along the LoC, or even a terror attack in India.'

Few observers of developments in South Asia are as prolific as the astute Michael Kugelman.

Kugelman, the Senior Associate for South and Southeast Asia at the Woodrow Wilson Centre, the Washington, DC, think-tank, is the go-to-analyst when journalists seek clarity on America and its complicated relationship with Afghanistan, India and Pakistan.

In August, on the eve of the soon-to-be-aborted NSA talks in New Delhi, Kugelman had told Rediff.com that 'Modi wants Pakistan to be a distraction, not a crisis'.

On Friday night, even though it was Christmas, Kugelman, below, left, kindly stayed up late to answer Nikhil Lakshman/Rediff.com's questions on Prime Minister Modi's Lahore visit and the reasons for the abrupt thaw in India-Pakistan relations.

How do you account for the sudden momentum in India-Pakistan relations after the deep freeze last August? If you were to enlist five reasons that provoked the change, what would they be?

The first reason can be discerned from the past. The history of India-Pakistan relations is one of ups and downs. These two countries have had their share of war and hostility -- but they've also had warm periods.

Just a few years ago, in 2011 and 2012, there were high-level meetings, cricket diplomacy, and all kinds of goodwill.

So in a sense you can say that after a very long down period in 2015, this relationship was due for a big boost. And that's exactly what it got.

The second reason is a personnel issue. Pakistan recently appointed a just retired general as its new national security advisor. India previously had little incentive to negotiate with Pakistan's civilian leadership because it lacked any control or influence over India policy.

The calculus has changed a bit now, given that one of Pakistan's senior-most civilian leaders now has a direct tie to the army.

In other words, from India's perspective, it simply makes more sense to sit down with the Pakistanis now because there's an expectation that negotiations can be more substantive.

The third reason is Modi's change of heart. My sense is that Modi, perhaps sobered by his party's shellacking in Bihar, or simply because it was clear that bellicose statements weren't getting his government anywhere, decided that it was time to start thinking in a serious way about some degree of renewed engagement with Pakistan.

Modi, let's not forget, took office last year wanting to improve relations with India's neighbours, including Pakistan -- and yet this objective got sidetracked at some point.

The fourth reason is the shifting calculus of the Pakistani military. After several months spent slinging allegations and accusations against India (which India was happily to reciprocate), the military may have decided that enough was enough, and that it was time to seek engagement anew.

We can assume that an ultimate aim of Rawalpindi is to get the sides talking again while keeping its eyes locked firmly on the prize -- a resolution of the Kashmir dispute.

The fifth and perhaps most consequential reason for the sudden warming period in India-Pakistan relations is none other than Uncle Sam. I'm sure that Washington has applied consistent pressure on both countries to resume dialogue.

In fact, we can assume that the series of events that culminated in Modi's historic visit -- the NSA talks in Thailand, the Sharif-Modi chat in Paris, and then the resumption of dialogue announcement at the Heart of Asia conference -- can all be attributed to US prodding.

Washington is fixated on the ISIS threat, and the last thing it wants is another war on the subcontinent -- or even the dangerous distraction of relations between two nuclear rivals on tenterhooks.

Were you startled by Mr Modi's visit to Lahore? The Indians claim it was a spur of the moment decision, taken after the two prime ministers spoke on Christmas morning. Do you believe that?

Or do you think this visit was weeks in the making? Has there been a similar gobsmacking visit by a leader to an 'enemy' country in recent times?

I'm certainly surprised, but not totally shocked. There has been a rapid intensification of high-level diplomacy in recent weeks, and there had been hints that Modi could visit Pakistan in due course -- though we all expected that visit would come well into next year, not at the end of the current year.

I can't imagine this was a last-minute decision, simply because of all the logistical and security precautions that would have to be in place some time in advance. Pakistani media reports have said that air traffic control in Lahore had been warned about the visit one day earlier, and I'm sure that's true.

I wouldn't be surprised if key stakeholders on both sides, and especially in Pakistan, were aware even earlier -- perhaps as far back as the Heart of Asia conference.

All this said, let's be clear. This visit, important as it was, is not a diplomatic breakthrough for the ages. It was really more of a courtesy call -- albeit one fraught with soaring levels of symbolism and considerable significance.

Modi did not come to hold substantive discussions with (Nawaz) Sharif. He did not come to present a peace plan. This was not a Nixon-goes-to-China type of thing.

Rather, Modi came to personally wish PM Sharif a happy birthday, and to mark the occasion of Sharif's granddaughter's wedding. Certainly the two spoke about various issues, but mainly they talked about the need to keep talking. That's important, but no game-changer.

The prevailing view in India is that the Americans forced both nations to walk the plank so to speak and hold talks. In your understanding, is there any truth in this?

Call me conspiratorial, but I can't imagine that so many diplomatic victories could have been achieved so quickly, and so suddenly after so many months of ice-cold relations, without some level of US prodding.

I would not describe it as a walk-the-plank type thing; I would think of it more as determined and firm American urging.

Yes, there's something to be said about the Indians and Pakistanis both deciding that it was time to get their act together after months of ugly tirades and angry rhetoric, and to push for a semblance of engagement.

Still, Washington has a strong incentive to put on its good offices hat and to try to get something done -- I don't mean in terms of getting the two sides to reach some sort of breakthrough deal, but simply to get them talking.

From Washington's perspective, it's better for India and Pakistan to speak to each other than to stew about each other.

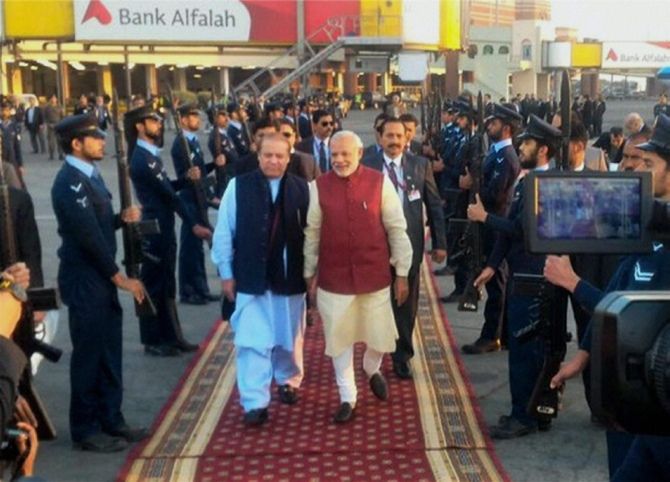

IMAGE: 'The newest variable, and arguably the one that would have propelled Washington to get involved in the India-Pakistan quagmire, is the ISIS factor. From Washington's perspective, it cannot afford for the subcontinent to once again become a flashpoint -- and especially a nuclear flashpoint -- at this juncture, when the US is trying to combat a nemesis that it has described as the biggest threat it has ever faced,' says Michael Kugelman.

What provoked the Americans to get so involved? Was it the threat of nuclear conflict (Pakistani leaders from Defence Minister Khawaja Asif to then NSA Sartaj Aziz spoke about the nuclear option when the talks failed)?

The Americans have always worried about the prospect of nuclear conflict on the subcontinent -- you don't have any other case of nuclear-armed neighbouring rivals anywhere else in the world.

Washington has been particularly concerned in recent months because of the upsurge in belligerent rhetoric between the two sides, as well as the alarming increase in Pakistan's tactical nuclear weapons.

But the newest variable, and arguably the one that would have propelled Washington to get involved in the India-Pakistan quagmire, is the ISIS factor.

From Washington's perspective, it cannot afford for the subcontinent to once again become a flashpoint -- and especially a nuclear flashpoint -- at this juncture, when the US is trying to combat a nemesis that it has described as the biggest threat it has ever faced.

This all provides a big-time justification for Washington to prevail on the Indians and Pakistanis to put their heads together to figure out a way to start talking again, and fast.

Or did the Afghan factor play a role? That Pakistan needed to be assured about India's intentions so that it could bring the Taliban to the negotiating table and maybe also counter the possibility of Da'esh spreading to Afghanistan?

There is a lot of hyphenation in the various relationships of the South Asia region, but in this case I'm not convinced that Afghanistan was a key factor in the India-Pakistan situation.

Let's not forget that Modi stopped in Lahore on his way back from Afghanistan, where he marked the opening of a new India-financed parliament building, and from Russia, where he finalized a precedent-setting deal that brought several Russian-made attack helicopters from India to Afghanistan.

In essence, India appears to be deepening its footprint in Afghanistan, which is not exactly a conciliatory gesture to Pakistan.

Also, India for now does not play a role in an envisioned Afghanistan reconciliation process, and I imagine that Pakistan would seek to bring the Taliban to the table regardless of the state of its relationship with India.

That said, if India-Pakistan relations are more civil, as they are now, than that presents opportunities and creates diplomatic space for Islamabad to keep New Delhi apprised of any developments in the reconciliation process -- a function that would ordinarily be performed by the Afghans or even the Americans.

All this said, the ISIS-in-Afghanistan factor can be a boon for India-Pakistan relations, given that both countries share an interest in expunging ISIS from Afghanistan and the broader region.

IMAGE: 'General Sharif is certainly on board about India-Pakistan talks; the progress of recent weeks could not have happened if he were not on board. This is Pakistan, after all, where no decision on India takes place without being subjected to an aye or nay from the military,' says Michael Kugelman.

How much was General Raheel Sharif's visit to Washington a factor in the changing India-Pakistan relationship? Do you have an idea about what John Kerry and Dr Ash Carter told the general?

Everything seems to have changed quickly since the general's visit to Washington -- Sartaj Aziz was replaced as NSA by a general who had General Sharif's trust; the two NSAs met in Bangkok; Mrs Swaraj visited Islamabad and now Mr Modi has visited Lahore.

Do you think General Sharif is now on board about the India-Pakistan talks? What must have convinced the general -- who seems to nurse a deep antipathy towards India -- to play ball?

This goes back to what I said earlier about US prodding. Yes, I'm sure that Afghanistan was a prime agenda point during the General Sharif visit, but you can be sure that India-Pakistan talks was featured just as prominently in the discussions. I'm sure that it also featured quite prominently in Nawaz Sharif's meeting with President Obama several weeks earlier.

General Sharif is certainly on board about India-Pakistan talks; the progress of recent weeks could not have happened if he were not on board. This is Pakistan, after all, where no decision on India takes place without being subjected to an aye or nay from the military.

Who knows exactly what might have convinced General Sharif to take the plunge and send his country into talks with India.

The conspiratorially minded may say it's all about ensuring that the dollars keep flowing in from Washington, or that it's all part of a grand design to put Kashmir back on the table; the more empirically minded would refer to General Sharif's background, which includes his having played a major role in shaping military doctrine on tackling internal militancy, and contend that he has an interest in pushing for better relations with India to allow Pakistan to focus more intently on domestic militant threats. There is likely some truth in all of this.

A hardline position on Pakistan has been Mr Modi and the BJP's raison d' etre. Mr Modi would not have undertaken such a dramatic change in Pakistan policy without guarantees from Washington.

What could those guarantees likely to be? Are we likely to see the extradition of maybe Dawood Ibrahim, if not Zaki-ur Rehman? Are we going to see positive movement on terror and Kashmir?

Here's where we need to be careful about jumping to conclusions. The US may have leverage over Pakistan, but it's not in a position to force the Pakistanis to do what the US (and India) may want it to do -- despite all the aid (much of it unconditional) that it provides to Pakistan.

More likely is that the Americans have pledged to work more closely with India on matters of major concern to India. Perhaps this entails Washington having told New Delhi that it will do more to freeze the foreign assets of Ibrahim, or that it will work more closely with New Delhi to share intelligence about terror threats, and so forth.

At the end of the day, despite progress and encouraging developments, there are still several red lines so far as Pakistan as concerned.

This includes, I fear, doing anything major about Lashkar-e-Tayiba or speeding up the judicial process for those involved in the Mumbai attacks.

Pakistan has demonstrated its desire to intensify its assault on anti-State militants, and even a new willingness to go after sectarian-focused militants, but the India-centered ones remain off limits.

All the US could have told India in this regard is that it will redouble its pressure on Pakistan to address the LeT issue -- even though both the US and India must realise that's a very tall order.

Don't you think Mr Modi has taken enormous political risk by this recalibration of Pakistan policy?

Don't you think Mr Modi has taken enormous political risk by this recalibration of Pakistan policy?

How do you see this government's Pakistan policy since it took charge? Has it been confused? Or do you think things have been happening behind the scenes between Mr Modi and Mr Nawaz Sharif, first in Kathmandu and then in Ufa?

Modi has taken tremendous risks in extending the olive branch to Pakistan -- because some of the largest critics of this policy are members of his own party or those close to it. He risks alienating members of the BJP rank and file, many of whom may not want a deeper relationship with Pakistan. This is, after all, a party that has been associated with strongly anti-Pakistan sentiment.

The risks have been magnified even further in the aftermath of the Bihar election debacle, which exposed the party's -- and Modi's -- vulnerabilities.<>/p>

Credit is due here to Modi -- he has been willing to swallow the political risk of alienating some of his supporters for the greater good of regional stability.

India's Pakistan policy under Modi has never been particularly clear. My sense is that Modi wants better relations with Pakistan, and has wanted this outcome since he became prime minister. He understands the merits of normalised trade and likely would want to use commercial diplomacy as a vehicle for better relations overall.

This policy clearly became very confused, though, and much of it can be blamed on domestic politics in Pakistan.

After an anti-government movement -- likely orchestrated by the Pakistani military to some extent -- put Nawaz Sharif in his place and cut him down to size in the summer of 2014, the army likely felt a need to assert itself further by taking a particularly hard line against India.

Hence the angry talk and rhetoric for much of late 2014 and almost all of 2015, as well as the provocations along the LoC. Modi and his government, given their nationalist bonafides, could clearly not sit quietly in the face of such actions, and they did not.

That said, once the two sides had vented themselves hoarse, and perhaps once the US started pushing them to quiet down, it was easier for Modi to get his original policy back on track. And that brings us to the events of Christmas Day 2015.

The last time an Indian prime minister visited Lahore was in February 1999, and we all know what happened some weeks later. What now? What do you expect from New Delhi and Islambad/Rawalpindi in the weeks to come? Can the Pakistan army still scuttle the rapprochement, like it did after Ufa?

I'd like to be an optimist, but it's hard not to rain on the parade of the euphoria sweeping both capitals, and certainly Washington, about this Modi visit to Pakistan. After all, we've been here before.

Back in 2012, there was all kinds of goodwill and high-level meets, and that all came to naught.

When it comes to India-Pakistan relations, seminal moments of progress invariably bring out saboteurs of peace.

There is always the possibility that the saboteurs will swing into action -- whether we're talking about fresh provocations along the LoC, or even a terror attack in India.

It's worth remembering that some top anti-India terrorists who had been quiet in recent years, such as Masood Azhar of Jaish-e-Mohammed, have suddenly come back on the public scene over the last year or so.

The key is to keep expectations low -- let's not assume there's going to be a Kashmir resolution anytime soon, much less a full-fledged peace accord. It's not happening.

Instead, let's hope that both sides can expeditiously take advantage of a window of opportunity that could slam shut at any moment.

The best way to do this is to seize on the low-hanging fruit -- try, for example, to finally consummate an MFN (Most Favoured Nation) deal that establishes a normalised trade relationship.

Above all, continuity is the need of the hour. The two sides need to maintain the momentum of the moment. And on that front, there is already good news, given the announcement that there will be Secretary-level talks in Pakistan on January 15.<?p>

That's very encouraging, and let's hope that more of the same will take place over the course of 2016.