'Assuming our past witnessed bloodshed and mayhem and large-scale destruction of temples, do we turn the clock back, avenge the past, and create the circle of death in the present?'

'This fervent wish to avenge the past constitutes the dominant political rhetoric of the last 25 years,' journalist and debut author Ajaz Ashraf tells Syed Firdaus Ashraf/Rediff.com

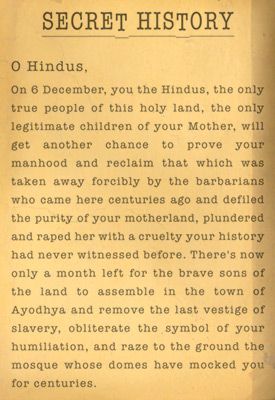

On 6 December, you the Hindus, the only true people of this holy land, the only legitimate children of your Mother, will get another chance to prove your manhood and reclaim that which was taken away forcibly by the barbarians who came here centuries ago and defiled the purity of your motherland, plundered and raped her with a cruelty your history had never witnessed before.

There's now only a month left for the brave sons of the land to assemble in the town of Ayodhya and remove the last vestige of slavery, obliterate the symbol of your humiliation, and raze to the ground the mosque whose domes have mocked you for centuries.

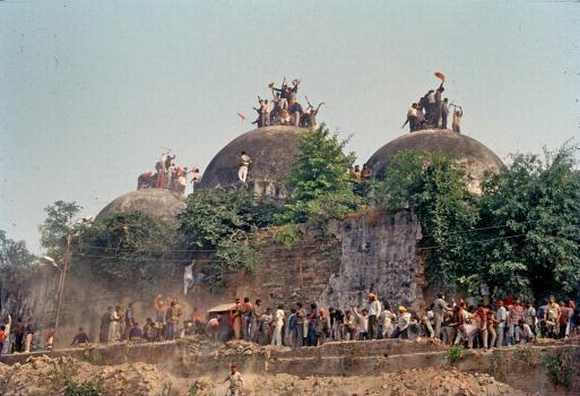

These lines can be haunting for those Indians who witnessed the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992.

The demolition led to murderous communal riots and the serial bomb blasts in Mumbai.

If you were born post 1993 and were too young to understand the impact of the Babri Masjid's demolition, here is your chance to know more about those dark days through journalist turned debutant author, Ajaz Ashraf's novel The Hour Before Dawn.

"The past is often rewritten, and harnessed, to justify the political agenda of the present. The effort to rewrite the past has become even more vigorous than what it was earlier. This is one of the themes of The Hour Before Dawn," Ajaz Ashraf tells Syed Firdaus Ashraf/Rediff.com in an interview conducted via e-mail.

"My novel is also about relationships and how these are impacted by cataclysmic events. It is also about finding a meaning in life, about making an inherently absurd life meaningful. This is decidedly the concern of today's young," he says.

What prompted you to write The Hour Before Dawn?

I was young at the time the Babri Masjid was demolished. Not only was it extremely upsetting, but the anger and hatred the Ayodhya movement generated was incomprehensible to me.

Its impact was searing and indelible. The innocence of school and college years, still quite fresh in my memory, was shattered, and the world seemed to have been turned upside down overnight.

To fathom this change, to make it intelligible, I turned to fiction. It was not only to understand myself, but also those who supported the demolition. This was beyond the pale of journalism.

The few years I had spent in the profession told me that fiction was perhaps the only way the truth about traumatic experiences could be narrated. This is because either the media isn't interested to know the truth or the profession imposes certain limits on the practice of journalism.

For instance, there are defamation laws you have to contend with in journalism; there is the market which the media doesn't want to offend; you are asked to adopt the voice of neutrality which becomes a ruse to dissimulate or obfuscate the reality.

These are not the constraints of fiction. Its starting point is to tell a lie convincingly, in the sense of making people believe in an event which hasn't happened, to empathise with a person who doesn't exist.

Therein lies the irony -- the avowed goal of journalism is to tell the truth, but it ends up, in many cases, concealing it.

By contrast, fiction uses a lie to speak the truth.

Second, one question which has always haunted me is: If a person isn't a believer, doesn't subscribe to any of the religions, then what can be the ethical basis of his or her action?

The Hour Before Dawn probes that, eventually providing a perspective from which the demolition of the Babri Masjid is judged an unethical act.

Third, my novel probes why an ideology appeals to one person and not to another even though the two might share the same socio-economic background. This is because of their distinct psychologies, which they acquire through their experiences in life.

For all these reasons, I took to writing The Hour Before Dawn.

Fifty per cent of India's 1.2 billion people are below 25. Do you think your book about the demolition of the Babri Masjid two decades ago will appeal to this new generation?

Fictional accounts are embedded in the social context in which these are created. Yet novels also transcend the social context to speak of themes and concerns which are perennial in nature.

Even otherwise, the socio-political and psycho-religious dynamics that existed during the campaign against the Babri Masjid still persist. What we see today is a bitter fight over the past, what it was and its meaning is.

Again, the past is often rewritten, and harnessed, to justify the political agenda of the present. The effort to rewrite the past has become even more vigorous than what it was earlier. This is one of the themes of The Hour Before Dawn.

My novel is also about relationships and how these are impacted by cataclysmic events. It is also about finding a meaning in life, about making an inherently absurd life meaningful. This is decidedly the concern of today's young.

How did the idea of 'Secret History' come to you? You have mentioned almost all the atrocities of Muslim kings against Hindus in the last thousand years.

In your research did you come across how many temples Muslim rulers destroyed in India over a period of 1,000 years?

Over the last 25 years, but also through much of the 20th century, we have had conflicting perceptions and interpretations of what India was under Muslim rule.

You had colonial historians who portrayed Muslim rule as the 'Dark Age,' because of the alleged religious persecution of Hindus, because of the seemingly unbridgeable divide between Hindus and Muslims.

This imagining of the past subtly promoted the idea that only the British could provide a just and stable governance to India. Much of this seeped into our textbooks that were taught during the first three or four decades of India's Independence, long before the NCERT (National Council Of Educational Research And Training) books were written and prescribed.

This communal narrative produced a certain kind of consciousness which, in turn, bred in a class of people the wish and desire to avenge the past.

This fervent wish to avenge the past constitutes the dominant political rhetoric of the last 25 years.

The 'Secret History' chapters seek to study that consciousness through the portrayal of the author who writes them. It is a peep into the author's psychology, exploring why a particular version of history appeals to this person.

As you can see, I don't wish to disclose the gender of the writer, for to specify it is to give away the climax of the novel.

Then again, The Hour Before Dawn is partly the story about the conflict over our past. In a work of fiction I couldn't possibly have opted for an academic treatment.

The 'Secret History' chapters fictionalise history, besides exaggerating narratives culled from textbooks, some of which pedal accounts of extremely doubtful veracity, in the sense that there are no historical sources to back them.

In today's India, history has come to resemble fiction, evident from the current claims that our forefathers had mastered modern technology in  ancient times. Why should a person feel the need to make such claims? This is the question asked of the author who is in my novel penning the 'Secret History' editions.

ancient times. Why should a person feel the need to make such claims? This is the question asked of the author who is in my novel penning the 'Secret History' editions.

Image: An excerpt from the 'Secret History' portion from the book's back jacket.

However, this isn't to say that there was no religious persecution, of whatever degree, in India's past. There was religious persecution right through our history -- and not only under Muslim rule.

To me, and I hope for the readers as well, the 'Secret History' chapters pose the following hypothetical question: Assuming our past witnessed bloodshed and mayhem and large-scale destruction of temples, do we turn the clock back, avenge the past, and create the circle of death in the present?

Or, to put it differently, in the context of India's history of caste-based persecution, should we segregate the upper castes, claiming their very shadow is polluting?

In the chapter of Deva Raya II you have mentioned how he ruled by dividing different Muslim rulers of the South and maintained peace. Why could that not have been done by other Hindu kings in different regions of India?

Again, this is an interpretation of history, a spin. It must be understood I have fictionalised history. I am also no scholar of history, I only studied it for my BA and MA.

Nevertheless, I suppose Deva Raya II succeeded in dividing the Muslim rulers in the South because he had greater power than them, because he could play the role of the arbiter.

But in pointing to this episode, I am also winking at the fact that despite Muslim rulers sharing the same religion, they could quite easily be divided.

In other words, power and self-interest were the motivating, as also determining, factors of those times, as they are today. This is precisely why so many Hindu kings cooperated with the Mughals.

It is possible the reader might wonder why there is no counter-point to what is written in the 'Secret History' chapters. But a close reading of those chapters will have the readers identify, and grasp, the rebuttals present in them. The 'Secret History's author cites the arguments of different schools of history in order to mock them.

Is it true that Akbar's religion, Din-E-Ilahi, had only 17 followers? Why could that religion never gather ground in India?

Yes, this is what I gleaned from history books I read for this section. I suppose Akbar's religion did not strike roots because he wasn't interested in spreading it. It is otherwise inconceivable that a powerful monarch could get only 17 adherents to the religion he founded.

In creating a new religion, which borrowed elements from different faiths, he was trying to unite the nobility, of which many were Hindus.

Your reason for Uma loving Rasheed is that 'Perhaps love is choosing a person through whom you try to redeem yourself.' Please elaborate.

We discover ourselves through relationships, those aspects of ourselves we perhaps don't even know exist in us. We also reveal ourselves to different people in different ways.

Relationships are about knowing about ourselves and also about becoming.

At times, this awareness of our selves comes long after relationships flounder or wither away or terminate. In the instance from the novel that you refer to, Uma recognises that through Rasheed she could undo the past, make amends, and redefine herself.

Could you during your research find out why Aurangzeb felt it compelling to re-impose the jiziya tax on the Hindus and why he had immense hate for the Hindu way of life?

The 'Secret History' chapters depict the typical rightwing Hindu's view of India's past. One of the reasons why Aurangzeb imposed the jiziya tax is spelt out in the chapter pertaining to him.

Obviously, the author argues against the reason. It is said the state exchequer under Aurangzeb had depleted, and there was pressure on him to enhance revenue, not least to stamp out the rebellions mushrooming around the country.

Some historians argue that he imposed the jiziya because the Muslims, unlike Hindus, were anyway paying zakaat.

But this apart, we must not look at our past in a monochromatic way. While Aurangzeb did demolish temples, there is ample evidence of him giving land grants to support temples. So, how do we reconcile the two contradictory facts?

Whatever your answer to this question, it isn't ethically justifiable to harness the past to create the circle of death in the present.

In the 'Secret History,' one of the posters written by right wing Hindu fundamentalists says 'No religion is as antithetical to nationalism as Islam.' Does this hold true even today?

The statement is palpably a wrong assertion. The characters of Wasim Khan and Rasheed Halim are an argument against this assertion in my book. If this assertion had been true, then it would also mean that a collectivity brought together because of religion won't witness sharp divisions.

Well, didn't Pakistan split into two, despite it and Bangladesh being predominantly Muslim? So, for Muslim Bangladeshis at least, linguistic, not religion, became the impulse of nationalism and the social glue.

Did you feel the book should have been named 'Secret History,' rather than The Hour Before Dawn? In the book, 'Secret History' comes in all the time, which Muslim bashing starts with a historical perspective.

I did not, largely because a very famous book of this name exists and which my own novel refers to in the opening pages.

The 'Secret History' portions, I think, are terrifying. It also represents a frightening, unsettling challenge to the characters in the novel and, by extension, to all of us as well. How are we to countenance this challenge?

I think it was Rabindranath Tagore who said, 'Faith is the bird that feels the light and sings when the dawn is still dark.'

In the darkest hour of the day we, like birds, need to keep faith. The Hour Before Dawn is so much about keeping faith, which dispels the mist of hopelessness, of darkness.

Do you feel in India Muslims feel besieged post the Babri Masjid demolition and specially after the Narendra Modi government refuses to take action against right wing Hindu leaders who talk about 'Ghar Wapsi' programmes?

Do you feel in India Muslims feel besieged post the Babri Masjid demolition and specially after the Narendra Modi government refuses to take action against right wing Hindu leaders who talk about 'Ghar Wapsi' programmes?

Yes, they do. But not only the Muslims or other religious minorities feel besieged -- liberal Hindus, secular Hindus, devout Hindus, atheists, women, people with an alternate sexuality feel besieged too...

Image: Journalist-Author Ajaz Ashraf.

In fact, all those who think the 'Ghar Wapsi' programme is ultimately about using force to compel people to accept a certain view, a particular belief, against their wishes. This thread is very much present in The Hour Before Dawn.

You have tried to touch the issue of 'Reformation of Islam' in the 'Secret History' chapters. Do you think that is possible considering the fact that many Muslim leaders and intellectuals failed to do so in their respective societies?

It is indeed possible. This issue is discussed intensely in the Muslim community. In The Hour Before Dawn it is expressed through the character of Wasim Khan, who advocates that people should read the Quran in the language they can understand.

His interpretation of Islam is liberal. And though what is called the Arab Spring collapsed at most places, it was a manifestation of what you can call the Islamic reformation, the spirit of which will be resurrected.

The author who writes 'Secret History' in the book wants to engineer such chaos, such bloodshed against Muslims that they would in their helplessness, exclaim, 'There is no God but Power.'

As a journalist, do you think Western countries are trying to do the same to the Muslim world what the author of 'Secret History' is trying to do?

The West is not interested in changing the religion of those whose countries they occupy or subordinate. It is primarily interested in exploiting their resources, finding a market, and ensuring they serve its geo-strategic interests.

For the believer, God is Power, in fact the Ultimate Power. It is this which inspires those who oppose the combined might of the West and its allies.

They believe that since God is the Ultimate Power whose blessings or support they have, they can vanquish the mightiest of their opponents possessing the deadliest of arsenal.

Finally, what happens to the character of Uma in the novel? Why did you want to keep it a secret?

It is best left to the imagination of readers. The most curious of them have been asked to direct their query to a particular e-mail address given in the book. The answer, as my novel says, will be provided then.

© 2025

© 2025