'I realised I didn't have to wait for a spectacular event or a character to emerge. All stories of ordinary people, of your family, are extraordinary,' novelist Yasmeen Premji tells Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com

Until a few years ago, Yasmeen Premji, left, was best known as Azim Premji's wife. According to Forbes, her husband -- chairman of Indian information technology major Wipro Limited and a philanthropist -- is the fourth wealthiest Indian, and the 61st richest man in the world, with a personal wealth of $15.3 billion in 2014. Yasmeen herself sits on the board of the Azim Premji Foundation and the Azim Premji University.

For two decades, Yasmeen -- a graduate of Mumbai's St Xavier's College and Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts -- had a secret. She was working on a historic novel, Days of Gold & Sepia.

No one-- even her family -- knew the secret, until she found a publisher.

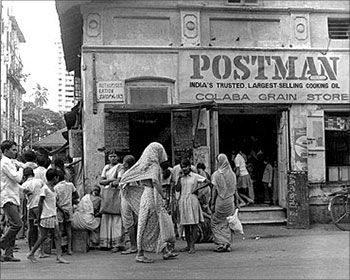

Days of Gold & Sepia is the rags-to-riches saga of Lalljee Lakha, an illiterate goatherd from Kutch and his journey to Mumbai, where he eventually becomes a textile mill owner and an opium trader. Yasmeen peppers her book with family lore, and historic incidents and facts -- from Bal Gangadhar 'Lokmanya' Tilak's call for Swaraj, to the Independence of India and the creation of the new nation of Pakistan.

Yasmeen was in New York recently for the American launch of her novel organised by the Indo American Arts Council. Aseem Chhabra/Rediff.com spoke to her towards the end of her trip.

I find it fascinating that it took you 20 years to write this novel.

Well, it didn't take me 20 years as such, because I didn't have an agenda and I didn't set out -- like the young people today -- to write a book and become an author. It's something I did for myself.

But you had written before.

I used to write. I wrote a few short stories when I was in college. And then I thought I should write this book, except that I wasn't pushing it. Today people churn out books in one month. So I waited for something to write on and I wasn't finding a subject.

The idea for this book came only when my father died, which was slightly more than 20 years ago. My mother taught us not to gossip. But now that my father was dead, it seemed okay to talk about my grandfather's time. It was no longer gossip, but it was history.

So, more stories started coming out of the woodwork. As it is we had grown up on stories from my mother and later from my mother-in-law. We heard a lot of family stories and I was fascinated by them.

It was then that I realised that I didn't have to wait for a spectacular event or a character to emerge. All stories of ordinary people, of your family, are extraordinary.

It's how you view them because they are yours and so they are special to you. Or you see some part of you in them. I knew that my grandfather came from Kutch. So I chose 1857 to 1947 and I set the novel in that period.

I didn't tell anybody about it. I didn't want to count my chickens before the eggs hatched. And there was no certainty that I would finish this. I thought let me not tell anyone about it. And I began to slowly gather information.

There was no one bearing down on me -- no family members pushing me, nor any publisher.

You use the word gossip. Gossip has a certain malicious tone, when people say, 'Oh my God, you know what happened... but when you are talking about your grandfather and you say it is history, how do change that from the tone of gossip to weave a narrative of the novel?

They were simple things. I know my grandfather's brother had a mistress and had children, who my brothers had met. And more things started to come out. So, I am talking small bits of gossip, nothing major.

Well, at that time it must have been gossip.

Yes. I am sure. And households went bankrupt. Little things like that are part of family lore. Depends on how you write it. It also depends on whether you tell someone a bit of news in a blank tone, or say loudly, 'Oh, you have to hear this!' If you loudly say, 'She wore a red cap today,' that can sound like gossip.

You had done some journalism.

I worked with Inside/Outside magazine as a writer.

You had written short stories. But you were not trained as a novelist. How did you bring these stories in the narrative form? How much did you change? You subtitle it as a novel...

It is entirely a work of fiction. Any author draws on his or her experiences of life. Things you have lived or seen through the eyes of others, or what you have read. It all rolls together and comes out in some form or the other.

That is true. But, you start with a story you heard from your mother, do you then change it a bit, add a character, change a name or the sex of the person? Those were careful choices you were making, right?

Yes, and I had to put it in a form that was readable. But it took a lot of work, and editing. One of the major challenges was the timeline. I am fascinated by history and I wanted to weave elements of it. So I added little bit about the history of Mumbai, how it was growing.

When you try to put in a certain bit of history in your narrative, you have to align it with your fictional characters' lives.

For example, in 1900, Lalljee Lakha goes to the Paris Exposition. So he must have made enough money to be able to go to Paris. And he meets Jamsetji Tata (founder of the Tata business empire) there and he knows him personally. That had to fit in.

You bring in other real life characters. (Mohammad Ali) Jinnah appears when he suggests that Lalljee should move to the newly created Pakistan.

Yes. And that makes it more plausible and real. It could have been possible that Tata met someone of the calibre of Lalljee. He must have been an upcoming person, but well off to go to the Paris Exposition.

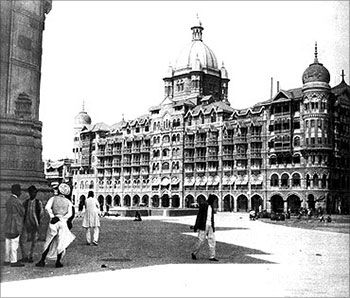

And Tata was there to acquire the spun pipes required for the original architecture of the Taj Mahal Hotel (which he built). So, he ordered them in Paris during that trip. I had read that somewhere. Since I was writing the book for myself, what amused me, I added to the narrative.

Tell me about the research process. You grew up in Mumbai, but to know the city of the 19th century must have required a lot of research.

The first part of research was to seek older people. I asked around family members if they knew anyone who had a 70 or 80-year-old grandmother. Because through their eyes, I could see 80 years earlier. And the world hadn't changed that drastically as it is changing now. It was very interesting to speak to people.

Then I started to read on the background of Mumbai. There was a seminar on the Sources of History of Mumbai and I couldn't believe it. I said to myself, 'This is a sign that this book has to be written.'

And the seminar was for a couple of days?

Yes. I signed up for that. Different people spoke and they gave their sources. Some I couldn't access in vernacular languages, but others I could sit and read them. I wasn't exactly writing a historic novel. The history would just appear sometimes. I wanted to paint a picture of that time.

At what stage did you say 'This is becoming a novel now'?

I was handwriting with pencil. And lead tends to fade. At one point I said, 'I am soon going to go up, so I better finish it.'

Come on, you are young.

Oh, thanks. But 20 years is a long time. I said at a point, 'I need to get it out.'

Unfortunately, neither my mother nor my mother-in-law are here. I dedicate the book to them because I got their stories. I was very close to both. That's my only regret in terms of time.

Would they have been okay with you talking about the family?

Oh, absolutely. They often said you love listening to the stories and love to write, so why don't you write?

How would you hear the stories from your mother and mother-in-law? They would talk to you sitting over chai or something?

We sat and chatted and these stories would come up. Sometimes, another old aunt would join us and she would be talking. I was interested and absorbing.

There is a story about Lalljee Lakha's daughter that is lifted entirely from family lore from my mother's side. These are stories you can hear over and over again. There is no question of giving the book away.

All stories are about when you are born, you mate or you do not mate and then you die. Between those parameters, all stories lie. So there are no surprises. If I tell you about a particular incident, it doesn't give the book away.

There is a story about two sisters, one dies of tuberculosis, leaving behind a child. The younger sister is persuaded very strongly to marry the widower. But she doesn't want to marry this man. But she had grown up in that tradition.

When the head of the household asks her, 'Do you want to marry this man?' she responds by saying, 'Whatever my mother wants.' Finally she gets into the marriage that doesn't work out and she is brought back to her father's house.

Did you have a routine where you would wake in the morning and write?

If I was that organised, I would have gotten it out a lot earlier. I wrote very erratically. Sometimes not for months, sometimes in the morning or at night.

But the characters lived with you for all this while.

Yes they did, but they changed as well, they took on lives of their own. As you have heard from other authors.

And there are other authors who have taken this long.

I was joking with someone that today's authors are so ambitious. They have already sold the book before they have started writing. They know what they want, what the market wants. I didn't care about what the market wanted. I knew what I wanted. I was out of sync with the times. But I was lucky to get a publisher.

So you approached a publisher and said. 'By the way, I have a novel?' I would imagine given your name and your husband's name, publishers will take your phone call.

I never thought of it like that. I was looking for a lit agent. Someone said you have to get a lit agent. So I spoke to a friend who had just published a novel. He had no clue if I could write or not so, he suggested I send the manuscript to a publisher.

At which point your manuscript was typed already?

Completely. So I sent it to a publisher and she just said, 'Instead of finding a literary agent, do you mind if I publish it?' That's how fast it moved. Then it moved from her to another publisher, but even they decided within the month. Because it was ready to go to the press. So I was lucky.

I had put in a lot of work already since I was also an editor. Churning it around, trying to tighten it. It did take a little more work.

How easy or hard was that once you had spent nearly two decades writing it, creating characters, although you are editing it also while writing?

There were things I cut. There is an old masi (aunt) in this book that Lalljee grows up with and who had occupied this position in his uncle's house of between being a servant and a relative. She is like a mother to the child.

I had written her story, which I think came out rather well, married off at the age of 12 to an older man with children. You know the usual sad story.

But one editor at the publishing house told me, 'We don't need this story. Everybody in India has a dukhi (sad) aunt.'

I had liked the way it flowed and I would have liked to have kept that in. But I made the exception and took it out.

But the masi is still there.

The masi is there, but her backstory is gone. I wanted to give all my characters their lives. But I was told that this makes us forget Lalljee.

That's one thing I learned th

at people want to see everything through the eyes of Lalljee, and you can't go out on a tangent.

I thought each of tho

se stories were strong enough in themselves. There was another section where I had added a discussion of euthanasia and then I stopped and asked myself, 'Who are you writing this for? This is entirely for you. You don't have to put it in this book.'

Did you know how the book was going to end?

Yes.

Did you make notes about your characters during the 20 years? That you wanted to capture key periods in their lives?

It was not period, but events. I knew that I was going to write about the life of the penniless man who walked all the way from Kutch to Mumbai.

At some dinner party I heard a man say, 'My grandfather walked from Gujarat to Mumbai.' And I said that's a nice way to put it. That he literally walked. That stayed with me.

Your family had no idea what you were working on?

No, they didn't. Once, my husband saw me working on the computer and he asked what I was doing. And I told him I was collecting all my old short stories.

And he liked the book? And your sons?

My husband doesn't read fiction. I think he liked it. He was said he was surprised.

My sons are also not readers. So one has read it and the other has not.

© 2025

© 2025