'The majority of transmission will be via people who are within two metres of one another.'

'The closer you are, the more likely that you'll be infected.'

The novel coronavirus, that causes COVID-19, has been in our midst, in India, for more than four-and-a-half months now.

Remember the first case was confirmed on January 30, 2020, in Thrissur, Kerala.

We have gradually learned to awkwardly and uncomfortably live with this intrusive virus, many of us still successfully keeping it beyond two metres away. Or killing it with soap, spirit, sanitiser and bleach, if it has, on occasion, sneakily breached the prescribed distance.

It helps to know your enemy and to understand more about the intrepid viral intruder of 2020.

Who better than distinguished virologist Dr Ian Lipkin to answer questions on how to live with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, that brings on COVID-19 in Part II of this two-part feature?

Has the virus, that causes COVID-19, mutated and is a mutated version running about India?

Can it live in our fridge? Is it in the air?

How exactly must you use soap kill it?

Dr Lipkin acquired an interest and expertise in quickly identifying and classifying the deadliest of viruses, among the 320,000* odd mammalian ones, that live on this planet, after being a bystander, as a post-doctoral research student, in the agonisingly long two-year battle in the 1980s to isolate the HIV virus that caused AIDS.

A physician and professor at Columbia's respective epidemiology, neurology and pathology and cell biology departments, he is also the director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at Columbia's Mailman School of Public Health and a proponent and promoter of the recently-established Global Infectious Disease Epidemiology Network (GIDEoN).

Dr Lipkin was also the scientific consultant to the film Contagion and feels that controlling the virus is as much about educating the public, in India too.

After the pandemic broke his centre co-opted famous actors into issuing effective public service announcements.

Bollywood too could take on this latest role, more successfully than it has till date.

Dr Lipkin spoke to an Indian audience on Friday, July 10, at an online event organised by Mumbai's Columbia Global Center for the Yusuf Hamied Fellowships Events lecture series about COVID-19, that has caused a global economic damage of $3.8 trillion already**.

He answered questions put to him by the audience, by Dr Yusuf Hamied, chairman of the drug company Cipla, by the media and by Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com:

What are the different strains of the COVID-19 virus?

Are there different strains?

This reporter writes that they hear that India has a stronger strain.

While some others say that India has less strong strain.

Is that true?

Well, the original virus, that came out of Wuhan, China, has been contrasted, dramatically, with the virus that's been circulating (since), and appeared to be more successful, in evolutionary terms, in becoming predominant worldwide.

That second strain is the one that infected me in New York.

There is evidence that it grows more rapidly; it grows to higher concentrations.

As to whether or not it causes more disease or not, I think that's still open.

I'm not aware of all the different phylogenetic (genetic diversification) analyses of Indian strains of the virus.

I can't say whether or not there's a different virus circulating in India, than there is in other parts of the world.

It seems there are now reports of bubonic plague coming out of China.

How should the rest of the world respond and react to those reports and prepare?

We will continue to see viruses and bacteria emerge as a result of the fact that we are impacting our climate, we're impacting our entire ecosystem.

And we have increasing travel and trade in a global network.

This is why I proposed -- and I'm strongly emphasising -- the importance of building a network where people can rapidly identify these agents and respond to them in a rapid timeframe, right?

This is something we desperately need. And this was the point of the GIDEoN network.

So yes, this is not the last infectious agent that we will see.

I don't even know if it's going to be the worst that we will see in our lifetimes.

How important is testing to the overall strategy of containing the outbreak?

And how do you feel about India's performance on the testing front?

If you think it's important, how can it be improved?

Testing is extremely important, because the majority of people who were infected with this virus don't even know that they're infected with this virus.

Many people are asymptomatic and during the period that they have not yet become symptomatic, they may nonetheless, transmit disease.

This is something that is becoming increasingly apparent, as we look at the way this virus is moving, particularly amongst young people.

And, therefore, without testing, you have no chance of catching people before they manifest disease, if they ever will.

It also allows you to get some sense as to whether or not you're being successful in controlling the spread of the virus.

Now India has not done very well in testing.

But frankly, very few places have.

South Korea has done well. Germany did well. Norway. And so on.

But obviously Sweden did not.

Testing has to be ubiquitous. And it will be expensive.

And that's one of the reasons why I showed you this test that we've developed that allows you to look at three different targets at the same time and to use robots so that you can do it much, much more rapidly and reduce the costs (by a team in Redwood, California, that employs to robots to process the COVID-19 test).

Dr Yusuf Hamied: I make medicines.

Professor Lipkin hasn't spoken, as yet, about the current regimen of medication that is being used for COVID-19.

He briefly mentioned hydroxychloroquine.

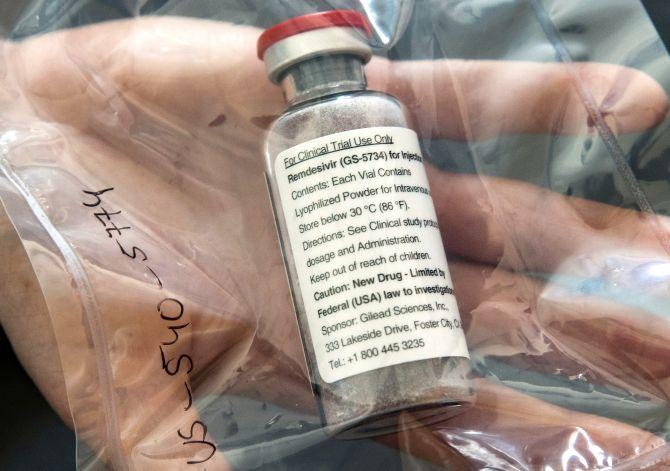

What is your opinion, Professor, on (antivirals) favipiravir and remdesivir?

One of the things that I'm very, very hopeful about is the use of inhaled or nebulised corticosteroids.

What is your opinion on medication?

Will there be a cure?

Remdesivir had a very modest effect.

It's the first one that had any sort of effect, and it had a modest effect.

And the inhaled version gives us the opportunity to give it to people other than through an intravenous method.

We have a large drug repurposing programme where we take a look at drugs that have been approved for work with retroviruses***, other coronaviruses***, filoviruses*** and we test them against bonafide live virus.

If I had something to tell you today, that you could start manufacturing, that is off the shelf, I would tell you immediately (smiles).

We will tell you as soon as we find it, but right now we're still looking.

You asked about steroids: It's a temporal progression sort of situation.

In the early phase of the disease, when the virus is invasive, you cause a number of things that are associated with the replication of the virus itself.

When the virus infects endothelial cells (interior surface of blood and lymph vessels), it can trigger the coagulation (clotting) cascade, which is why you're getting strokes and infarcts (tissue deaths) of different types in the periphery, as well as in the heart, and in other organs, the liver and the kidneys and so forth.

And there's a direct effect, as I say, because endothelial cells have receptors -- they have this ACE2 receptor (main cell surface receptor to which the novel coronavirus attaches itself). In the lung, it's obvious, you get this thickening of the alveoli, right, so that you don't get good air exchange.

Now, as you move into the latter part of the infection, roughly Day 10 to Day 12, there's an immune response when you begin to see antibodies coming up and so forth. And that cytokine storm (over-severe immune reaction) is impacted by the dexamethasone, or probably any steroid you want to use.

But if you give dexamethasone early, you can facilitate the replication of the virus and cause even more damage.

The dexamethasone is very important in preventing the cytokine storm, but it's not so helpful early on.

What we need is really several things:

We need antibodies, that are going to be useful.

We want to get away from (the use in treatment of) plasma towards monoclonal**** antibodies (made by immune cells or various types of WBC or white blood cells) that are going to be specific and which are going to prevent the attachment of the virus.

We're going to need drugs that are going to work on an intracellular basis, and we're going to need drugs that impact the host immune response.

We need all of these things, in concert, to get this under control.

If we had a drug that was 100 per cent effective, then the vaccine would be less important.

But right now, my hopes are really pinned on the vaccine.

Dr Yusuf Hamied: Which vaccine?

Yes, yes, I will tell you.

I like the RNA vaccines myself, because they're very cheap to manufacture, and they grow inside the cell.

There are several different types of vaccines people are making.

Some are making it with killed virus (particles of an inactivated virus).

The problem with the killed virus vaccine is it doesn't induce the correct type of immune response.

You want something that's growing inside the cell.

I'm not a fan of adenovirus vaccines (using an adenovirus as a viral vector or tool to make vaccines for other infectious viruses) because they require boosters. And because there are some preexisting immunity adenoviruses may impact in some populations.

But I like the DNA vaccines and the RNA vaccines.

There are I think 10 RNA vaccines right now that look very, very good.

Well, I've had COVID-19 and I'm hoping -- yeah, I got very sick -- so I'm hoping that I'm immune.

I don't know if I am. But I hope that I am immune.

Dr Yusuf Hamied: If you got it -- COVID-19 -- once, can you get it again?

There's only one monkey study -- very small -- suggesting no.

But then there's some human data that suggests yes.

I think that there are people who have been exposed to SARS coronavirus, Type 2 (that causes COVID-19), who had a very mild immune response, who can probably be re-infected.

The good news -- and this is just anecdotal -- is that if you get a second bout, it doesn't appear to be as severe. It is different than dengue in that way.

Dr Yusuf Hamied: Why is it that more diabetics are dying from COVID-19 than non-diabetics?

Well, more diabetics die of infectious diseases than anybody else, because there are a number of problems.

If you have a hyperosmotic intracellular and intercellular fluid (high osmotic pressure), immune molecules don't move as well.

You have problems with your vasculature (vessel system), right?

So, you can't deliver T cells (lymphocytes or WBC) and B cells (another kind of lymphocyte or WBC to fight disease) and other things as well.

But I don't think there is anything specific to COVID-19 in this regard.

This is also true with other infectious diseases.

Dr Hamied: Is it purely a lung infection, or are other organs also involved?

Oh no, this is a broad infection.

The ACE2 receptors are distributed throughout the body -- so you have them in the lungs, you have them in the respiratory tract, you have them in the endothelial cells, you have them in a wide range of organs.

This is a systemic infection.

Remdesivir, it seems, is very popular in India and seems to have helped save lives.

Perhaps you feel it's not as successful as it seems, based on your (earlier) comments.

I think remdesivir is a drug that has a role.

But it is not the panacea that we all hope it will be.

If we're thinking in terms of a drug, which is going to have a big impact, it's going to have to be a drug that's going to be orally available, so it can be taken widely, for people who've been exposed.

And it should have a dramatic effect, like Tamiflu has, on influenza.

We don't yet have such a drug.

If you are cleaning or soaping something for disinfection, do you need a fresh application of soap each time, for each object, or once your hands are well-lathered, can the same lather work twice or three times even?

It can.

This is an envelope virus.

So, soap will break it up and will be very good for eliminating it.

If you're talking about solutions, like hand sanitiser and such, as long as they're 60 per cent or better in ethanol, you should be good.

How does the virus do in high heat, such as 100 degrees Celsius versus in the cold?

Does the virus stay alive, but dormant possibly, in an object or food item in your fridge or freezer?

Well, let's start with temperature, I guess, which was the beginning of the question.

Particles hold humidity as a function to some extent of the temperature. Now, this obviously doesn't pertain in deserts.

But in India, where you have rain and so forth, it does.

The heavier particle, the shorter the distance it will travel with a cough or a sneeze.

So, when you are spending a lot of time outdoors, and if you have a dry heat, the transmissibility of the virus is reduced.

That doesn't mean that it's zero.

It simply means that it's lower than it would be otherwise.

There was a hope that as we moved into summer months in the temperate zones, that the incidence of disease would drop accordingly.

We can't say that it's dropped.

IMAGE: Dr Ian Lipkin. Photograph: Kind courtesy Columbia Global Centers, Mumbai

IMAGE: Dr Ian Lipkin. Photograph: Kind courtesy Columbia Global Centers, MumbaiBut that's probably because human behaviour has not supported what would have resulted in a drop.

It might have been worse still, if we were in the winter months.

We are anticipating, that as we move back into fall and into winter, in the northern hemisphere, that there will be an increase in disease.

Furthermore, it'll be more difficult to figure out who has influenza or an adenovirus (a more common, less harmful group/family of viruses that routinely causes coughs, fever, diarrhea, sore throat, conjunctivitis), or other viruses, versus having the (novel) coronavirus infection, that's travelling all over the world.

Now the virus has the ability to live on surfaces, for some period of time. It varies with the surface.

On metal -- with the exception of copper, which it apparently can't tolerate -- on certain metal surfaces and on plastics and leather, it can exist for more than 24 to 48 hours.

On the other hand, on softer, more porous substances, like paper and cloth, it appeared to have a shorter, viable timeframe.

In refrigerators, I don't know that anybody's actually measured it, but it is true that if you freeze this virus, it can be recovered.

This is a problem.

What many people do, to reduce risk, is if they bring something in from the outside, that has the potential to have been contaminated, if they don't have the ability to wipe it down, they will leave it in place for 24 to 48 hours, before they'll bring it into their homes.

Do you have any comment on the latest letter from various scientists around the world commenting on the virus being airborne?

Is there evidence that it's airborne?

There is some evidence that's beginning to emerge that suggests that it may be airborne.

By airborne what we mean -- for those of you who aren't familiar with the term -- is that the virus has the ability to remain suspended in the air for long periods of time.

The majority of transmission, however, be via people, who are within two metres of one another.

In fact, the closer you are, the more likely that you'll be infected and this is one of the reasons why maths are so important.

The load of virus on a fomite is not necessarily that large.

But in India, where the population density is great, especially in urban areas, and surfaces have huge handling, such as a plastic packet of milk delivered to your doorstep, can the risk from fomites be higher?

It is a risk.

There's no question.

And I think again, the same issue pertains.

If you can wipe it down with something which has soap or has alcohol, you would dramatically reduce risk.

If it is not perishable and you have the ability to leave it alone for 24 to 48 hours, like something which is a boxed good, that's also helpful.

In addition, ultraviolet light has the ability to neutralise the virus -- and there's ultraviolet light in sunlight.

*According to Dr Lipkin, there are at least 320,000 mammalian viruses, but the number is probably closer to a million, that would take $6.3 billion to discover, as per a 2013 study.

**According to a University of Sydney study published a few days ago.

*** ~A retrovirus is a kind of RNA virus that, when it invades, introduces a replica of its genome into the host cell's DNA, like HIV-1 and HIV-2.

~Filo viruses belong to the family Filoviridae viruses, like Ebola, originally of west Africa and the Marburg virus, first isolated in Germany in 1967. Filoviruses form virions or infectious filamentous viral particles and their genome is encoded in a single-stranded negative-sense RNA, incapable of coding messenger RNA.

~Coronoviruses are RNA viruses that cause respiratory-track illnesses, like COVID-19, SARS (first identified in Yunnan, China), MERS (or camel flu first identified in Saudi Arabia) and the common cold.

***Monoclonal antibodies are made by identical immune cells that are true copies (genetically identical) or clones of the parent cell.

Feature Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com