'Whatever the result on December 18, Rahul has succeeded.'

'He has taken the battle to the rival's territory, and forced him to take him more seriously than he has done so far, or would have wished to.'

'A party, dominating and powerful as the BJP today, is spending all its time attacking the leader of one with just 46 seats in the Lok Sabha, and in the woods in Gujarat for 22 years.'

'This isn't the script the BJP had written,' says Shekhar Gupta.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The 'trending' questions these days are: Have you been to Gujarat? What's your feeling from the ground? What do you sniff in the air? Is there going to be a change?

The first is a simple one for me to answer: No, I haven't been to Gujarat in this campaign. And I do not have the olfactory powers to sniff change in the campaign air.

I love dogs, but I am not one.

What I can do, however, is read political actions, responses, faces, utterances, shifting tactics and strategies, goal-posts, the vocabulary and grammar of a campaign, and changed rules.

Those tell me whether or not there is change in the air of Gujarat, and irrespective of what the result is on December 18, the BJP is caught in a state of nervousness not seen since 2014.

They are worried about Gujarat, they are surprised by the new commitment Rahul Gandhi has shown, and the traction he is getting.

They acknowledge the anger on the ground, particularly among the young.

They rue the 'messing up' of their own key caste equations, especially with the Patels.

They even complain about the ineffectiveness of the local leadership.

We haven't seen this mood in any election since the winter of 2013, when the party swept Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh.

Nobody in the BJP even vaguely suggests or accepts they could lose. But the assertion they make most emphatically is a kind of negative self-assurance: Oh, we simply can't afford to lose Gujarat.

Do you think Modiji and Amitbhai will let such a calamity ('vipada') come to pass?

See how Narendrabhai is campaigning. And even if there is anger among voters and a 22-year anti-incumbency, do you really think the Congress has the wherewithal to bring the voters out?

Amitbhai will beat them in the battle of the booth. Look at the machinery he has built.

All of it is said with great confidence. On careful reading and hearing, though, you could conclude it is all said to build self-assurance -- to convince yourself rather than an outsider who might have doubts.

This desperate search for conviction is nervousness.

There is one big difference between the Gujarat campaign and any other that the BJP has fought in the Modi-Shah reign. It is the only one they are fighting not as underdogs, but as front-runners and incumbents.

In all others (barring Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh in 2013) they were challenging incumbents. I am leaving out Punjab and Goa because the BJP was the junior partner in one and the second is much too small.

In Gujarat, on the other hand, the BJP carries the baggage -- or fuel, depending on how you look at it -- of double-incumbency.

Not only does it rule both the state and the Centre, the same two leaders rule both for their party: Narendra D Modi and Amit A Shah.

BJP leaders may argue that this is today's reality, that each BJP state is controlled as closely by this new high command as Gujarat. But it isn't the whole truth.

Both the prime minister and his party chief come from Gujarat, impressed the entire country's voters with their two-and-a-half-term Gujarat performance as the highlight on their CVs, and administered the state firmly, as if it was under President's Rule.

It obviously did not work as well as they might have thought. Within three years, despite being under the high command's direct control, the state has lost its way.

It has already had two chief ministers, both unpopular and ineffectual, the second worse than the first. The state's booming economy, fired by both mercantile and manufacturing activity, has stalled. Young people are understandably restless.

Contrary to the stereotypes that have grown over the decades, young Gujaratis have never been politically docile or unquestioning.

In the pre-Emergency era, the Navnirman movement found its feet here. Later, in 1985, as the fairly-recently submitted Mandal Commission report became contentious, the first protests came from Gujarat -- that story was also my first tour of duty in the state, and as usually happened with all unrest in Gujarat, caste riots soon took a communal turn.

We err in seeing only the Hindi heartland as politically volatile, probably because Gujarat has seen two long epochs of stability under strong leaders: Chimanbhai Patel and Narendra D Modi.

The rise of young caste-group leaders -- Hardik Patel, Jignesh Mevani and Alpesh Thakor -- is a sequel to the film we have seen in the past in Gujarat politics.

They have moved into the power vacuum that Mr Modi and Mr Shah's move to New Delhi created. Two generations of Gujaratis had lived under two strong leaders, and prospered. They liked the arrangement and miss it.

In Mr Modi, they had a chief minister the party high command called before any decision -- even stalwart L K Advani depended on him for his Lok Sabha seat.

They are no longer used to having a chief minister who calls New Delhi for every decision. In any case, this was always the Congress model, never the BJP's.

This shifting of the party's centre of gravity has messed it up in the state. No surprise that it is divided, with groups and rivalries.

And no surprise, therefore, that there is nervousness.

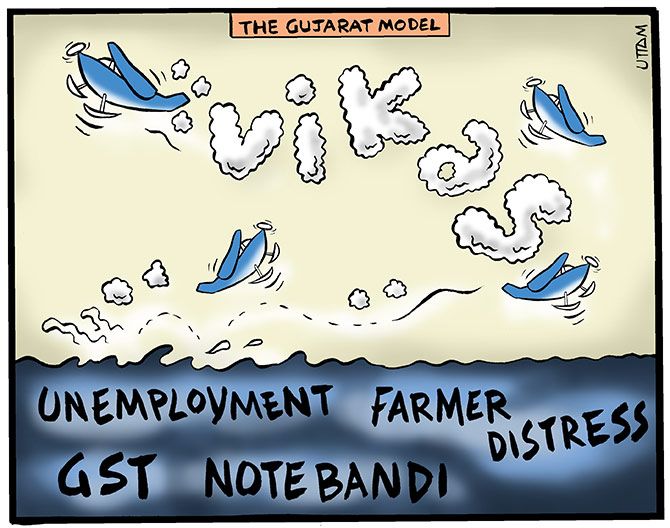

In 2014, the promise and slogan that swept Mr Modi to power was his 'Gujarat Model'. His era in power was marked with unprecedented industrial, agricultural, and infrastructure growth.

There was also considerable administrative reform and innovation, particularly in the areas of power and irrigation.

He found great adulation and endorsement from businessmen, and after five wasted years of the crisis-ridden UPA, the country voted for him, suspending the memory of the 2002 riots and accepting the new branding of Mr Modi as 'Vikas Purush' (man of development) rather than the epithet his opponents used for him, 'Vinash Purush' (man of destruction).

If one thing has disappeared from his and the BJP's campaign in Gujarat over the past three weeks, it is 'vikas'. The 'Gujarat Model' brought him power nobody has had in three decades, but it is not the key point of his Gujarat campaign agenda.

It is Rahul Gandhi and his slip-ups, identity, Aurangzeb, Khilji, Nehru-and-Somnath Temple, which register Rahul signed, and what Kapil Sibal is saying on Babri/Ayodhya in the Supreme Court.

Mysterious old Pakistani generals are surfacing on commando-comic channels 'endorsing' the Congress and Ahmed Patel as chief minister. It is back to identity (mine and my rivals'), anti-minorityism, the Gandhi dynasty.

It is almost like a return to 2002, bar the invocation of 'Mian Musharraf'.

This is a change. In our electoral politics, the key differential in campaigns and approach to voters is incumbency, for or against.

It is a rare occasion when a formidable double incumbent (22 years in the state and now with a fully majority at the Centre) is fighting as if it were an underdog and the Congress the incumbent.

We understand that while the Congress has been losing in Gujarat for almost three decades now, it has always had about 40 per cent committed votes in a bipolar state. It is, therefore, always a power.

Now go back to the campaign reports and videos of the earlier campaigns, especially 2007, 2012 and 2014. The thrust shifted from adversaries to Mr Modi's own achievements as his power grew and consolidated after repeat victories.

A combination of economic missteps, poor local leadership, and failed remote-controlled governance have created this muddle for the BJP in a state they should have won en passant or, in the more familiar, 'chalte chalte'.

Now, it is a hard, nervous climb.

To that extent, whatever the result on December 18, Rahul has succeeded. He has taken the battle to the rival's territory, and forced him to take him more seriously than he has done so far, or would have wished to.

A party, dominating and powerful as the BJP today, is spending all its time attacking the leader of one with just 46 seats in the Lok Sabha, and in the woods in Gujarat for 22 years.

This isn't the script the BJP had written. This is the reason they are furious, and nervous.

By Special Arrangement with ThePrint

© 2025

© 2025