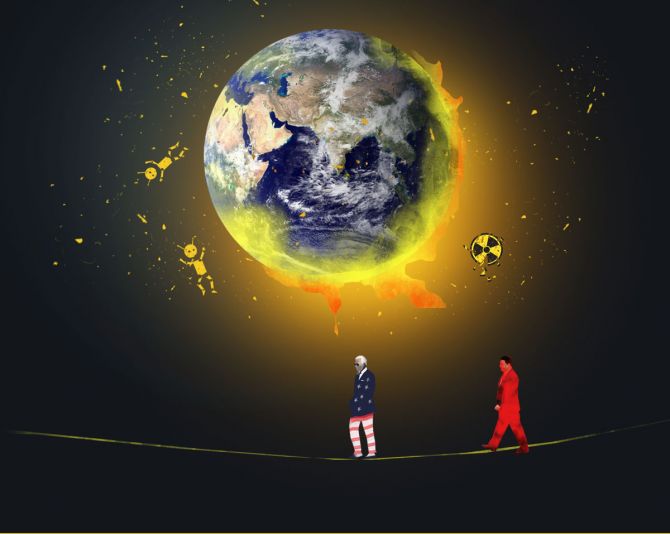

The first five months of 2023 have witnessed at least six major events/trends that augur badly for global economic and socio-political prospects, points out Shankar Acharya, former chief economic adviser to the Government of India.

Last December, I had predicted that calendar year 2023 would be worse for the world economy and polity than the already bad 2022.

At mid-year, in economic terms, it is certainly shaping up that way.

The IMF's April World Economic Outlook (WEO) projects global growth, at market exchange rates, at a low 2.4 per cent, significantly lower than the 3 per cent recorded in 2022, though a little higher than the 2.1 per cent foreseen in the October 2022 WEO (mainly because of anticipation of somewhat better performance of the economies of the US, China and Russia than forecast earlier).

The April 2023 WEO also foresees growth of world trade in goods and services will fall sharply to 2.4 per cent in 2023 from 5.1 per cent in 2022.

These numbers from the IMF and other international agencies will bounce around with every forecast as the year rolls on, but the broad thrust is unlikely to change: Global growth of output and trade in calendar 2023 will be significantly lower than in 2022.

More importantly, the first five months of 2023 have witnessed at least six major events/trends that augur badly for global economic and socio-political prospects in the medium-term.

First, in the critical domain of Climate Change, the April 2023 annual report of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) details the flood of continuing bad news relating to increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, the decline in sea ice and glaciers volumes, the rise in global mean sea levels, the rising concentrations of the main greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and other deteriorating parameters.

Ominously, in a mid-May update, the WMO warned that the confluence of rising greenhouse gases and a predicted El Nino weather pattern meant that “there is a 66 per cent likelihood that the annual average near-surface global temperatures between 2023 and 2027, will be more than 1.5 degrees C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year”.

Basically, key (mostly rich) nations have simply not done enough to tackle the problem as their short-term political interests almost invariably trumped the long-term global good. Nor is the outlook for serious action on mitigation promising.

Second, the last few months have witnessed an explosion of popular applications of generative artificial intelligence (AI), exemplified by the soaring use of ChatGPT, a type of large language model (LLM) and other similar chatbots.

AI has been around for many years, but the advent of generative LLM chatbots has sharply increased the social and political concerns about its unregulated development and applications.

Well-known senior developers of AI and thinkers have called for regulation of this 'genie' before it is too late to prevent destructive consequences.

Renowned Israeli philosopher-historian Yuval Harari pointed out last month that language has been 'the operative system' of every human culture and civilisation and generative AI has essentially 'hacked the operative system of human civilization'.

Initiatives for sensible and viable regulatory mechanisms are under active consideration in Europe and the US.

How they work or don't may have lasting consequences for humankind in future.

Third, nuclear accidents have been around for at least half a century (such as Three Mile Island in the US in 1979, Chernobyl in Ukraine in 1986, and Fukushima in Japan in 2011). But the Ukraine war, nuclear proliferation and other factors have greatly heightened risks over the past few months.

The International Atomic Energy Agency pointed out in its Update 160 statement last week that Ukraine's Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, the largest in Europe and operating in a war zone, 'has been without external back-up power for three months now, leaving it extremely vulnerable in case the sole functioning power line goes down' as it did on May 22, forcing it to rely on emergency diesel generators 'for reactor cooling and other essential nuclear safety and security functions' a clearly unsustainable situation (now worsened by the Kakhovka dam breach).

More generally, questions are being raised about the integrity of Pakistan's nuclear command and control system as the country's 'perma-crisis' (as The Economist calls it) rolls on with open hostilities between the military government and Imran Khan's party, against the background of an imploding economy.

In a less 'accidental' nuclear domain, the recent reports of Iran being days away from having sufficiently enriched weapons-grade uranium for a few nuclear devices, combined with the stated policy of the hard-right Israeli government and the recent weakening of judicial checks on it, have certainly raised the likelihood of a pre-emptive Israeli attack on Iran's nuclear facilities, with unknown, dangerous consequences.

Fourth, the tragi-farce played out in the world's most economically and militarily powerful nation over the past few months on the issue of raising the self-imposed debt ceiling in the US illustrates the high costs of deep political divisions in the country.

The agreement finally enacted days before the US government defaulted on some of its debt, pleases very few.

It merely postpones the essentially unresolved issue by two-and-a-half years (till January 2025) at the cost of some cuts in earlier approved social spending. And January 2025 is when a new President and Congress will be sworn in, with little time to resolve the unsolved dilemma.

Meanwhile, holders of US dollar debt instruments all over the world will, no doubt, be searching desperately for the holy grail of viable alternatives, imposing potentially significant costs on the world economy.

Fifth, China has ratcheted up its aggressive stance and actions towards Taiwan and the Taiwan Strait, despite some recent overtures from the US to reduce tensions.

The possibility of a fraught military 'accident' at sea or in the air has clearly increased. No clear solution is in sight.

Last, but by no means least, it looks increasingly likely that the next US presidential election in November 2024 could be a contest between two gerontocrats, Joe Biden and Donald Trump.

The former will be almost 82 then and vulnerable to concerns about his physical fitness.

The latter, three years younger, has, aside from a number of serious pending investigations and charges against him, had his mental fitness for the job questioned by many who have worked with him earlier.

The very possible return of a Trump presidency bodes ill for the world's polity and economy.

Dr Shankar Acharya is a honorary professor at ICRIER. Disclaimer: These are Dr Acharya's personal views.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025