'China, which had earlier blockaded New Delhi's bid to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group by citing the nuclear non-proliferation law, finds itself in an awkward position and international isolation.'

'However, India needs to pursue a policy of mediation between China and the Southeast Asian countries for regional security,' says Srikanth Kondapalli.

While China lost face in the International Court's rejection of any 'historical and indisputable claims' over the South China Sea, India needs to take the initiative in mediating between China and the affected Southeast Asian countries for lasting regional peace and stability.

As widely expected, the Permanent Court of Justice at The Hague delivered its verdict on The Philippines complaint on South China Sea issues. The verdict is direct, unambiguous and categorical on the sovereignty claims, environmental issues, fisheries, and freedom of navigation.

These will have a major impact on China, but also on other countries such as India in coming years.

The verdict is direct, and unusual in countering China's carefully, if controversially, crafted recent discourse of 'historical' and 'indisputable' claims over of over 90 percent of the 3.5 million square kilometres (about the size of India) maritime territory of the South China Sea.

The court slammed China for obstructing with Filipino fishermen's livelihood, clarified that sovereignty claims cannot be obtained through historical claims or artificial reef build-up and international trade should not be impeded by any country.

China termed the judgment as 'illegal' and 'ill-founded' and refused from 2013 to partake in the legal proceedings.

In the last two years China upped the ante by unleashing its 'three wars' -- propaganda, legal and psychological warfare -- to enhance its bargaining power but finds itself in an awkward position in the international community after the verdict.

The verdict is expected to have a long-term impact on China's domestic politics.

In recent times, President Xi Jinping and his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao moved away from patriarch Deng Xiaoping's sober position on the South China Sea issue and actively involved in restructuring the regional dynamics by constructing artificial reefs, militarisation and forcible deployment of oil rigs in the region.

Firstly, the verdict will be gradually played out in the Communist Party's factional struggles and a harbinger for gradual change in China's politics, although Leninist 'centralism' could come to the rescue of the powers-that-be in the shorter term.

Already, President Xi's anti-corruption campaign had alienated some in the top political brass benefited by reforms. While no major political changes are expected at the 19th Party Congress due next year, rival factions could implicitly use the verdict to bargain for key positions.

Secondly, a small but powerful faction in China -- mainly propped up by the military and conservative elements -- are likely to invoke Chinese 'exceptionalism' and argue in vain for walking away from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea -- UNCLOS -- treaty much like the North Koreans did in the early 1990s from the nuclear treaty.

However, the costs of such misadventure are likely to haunt China's 'new normal' economy which is much integrated in this globalisation era.

As China began investing abroad in substantial terms (in 2015 about $128 billion) and invokes investment protection treaties, international litigation could prove costly. China's flagship Silk Road initiative is also likely to be affected.

Thirdly, China is likely to move back in the medium term to adjust to the verdict in a pragmatic manner by approaching the disputants in the South China Sea and propose a 'win-win' deal with the United States.

However, despite the court's caustic remarks on the militarisation of the region, China is unlikely to vacate the artificial reefs or remove missile batteries and other military assets from the region in the long-term.

Despite the verdict, China is likely to pursue long-term strategic domination of the region.

Fourthly, the verdict is likely to have more consequences at the regional and global domains. China mobilised 60 countries in support of its claims in the South China Sea in the last few months.

With the verdict, many of these countries are expected to move away from Beijing's position, thus depleting China's 'attractiveness' in the international domain.

Initially, the disputants in the region, like The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and others are expected to be vindicated and emboldened with the court's caustic comments on China.

While China had assiduously built up its relations with these countries with a 'carrots and sticks' approach, and could still insist on 'bilateral talks' and 'peaceful resolution,' other claimants are likely to flaunt the judgment to counter or seek concessions from China on a range of issues.

The much divided house of ASEAN at its Phnom Penh meeting is likely to be regrouped in coming years.

Also, countries which have argued for freedom of navigation and overflight in the region like the United States, Japan, India and others feel vindicated with the judgment and renew their efforts.

The US had conducted freedom of navigation operations four times in addition to overflights in the region. Japan had promised aid to The Philippines as a part of its 'collective self defence' efforts.

India finds the judgment offering new possibilities. In bilateral declarations with The Philippines, New Delhi acknowledged the region as part of the West Philippines Seas and refused to buy the Chinese discourse on the South China Sea.

Since 2008, China had sent 21 naval contingencies to the Indian Ocean region, explicitly to counter piracy but implicitly to project power in the region as evidenced by its amphibious operations, air defence roles, testing its military-civilian dual use capabilities of evacuating thousands of Chinese from war-torn North Africa and West Asia and submarine visits.

With the verdict terming the South China Sea as international waters, the decks are clearly widely for conducting freedom of navigation in the South China Sea.

India, which dispatched four naval ships to the region in late May and currently operates in the region, can now plan for further contingencies to protect its maritime interests in the region.

For India over 55% of trade passing through the South China Sea is at stake.

India, which had observed the UNCLOS provisions and obeyed Bangladesh's possession of islands in the Bay of Bengal, clearly scored higher marks than Beijing on a similar issue.

China, which had earlier blockaded New Delhi's bid to join the Nuclear Suppliers Group by citing the nuclear non-proliferation law, finds itself in an awkward position and international isolation.

However, India needs to pursue a policy of mediation between China and the Southeast Asian countries for regional security.

Srikanth Kondapalli is Professor in Chinese Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University.

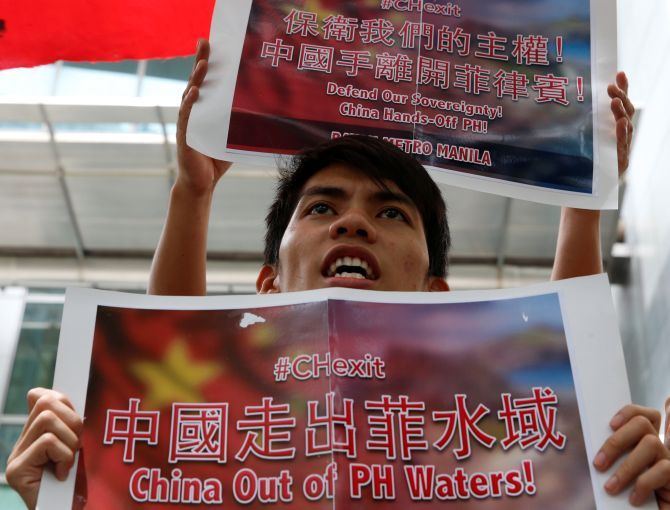

IMAGE: Demonstrators at a protest over the South China Sea dispute outside the Chinese consulate in Makati City, Metro Manila, The Philippines. Photograph: Erik De Castro/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025