'Lee Kuan Yew told me he used to look to India, especially the writings of Nehru and Sardar Panikkar, for guidance on governance.'

'It's ironic that India should have so much to learn of the spirit of democracy from his son,' notes Sunanda K Datta-Ray.

Forty-three-year-old ethnic Punjabi Pritam Singh, leader of Singapore's Workers Party, has made history by becoming the island republic's very first prime minister in waiting.

In this respect, tiny Singapore, supposedly saddled with a controlled political system, has upstaged the world's largest democracy.

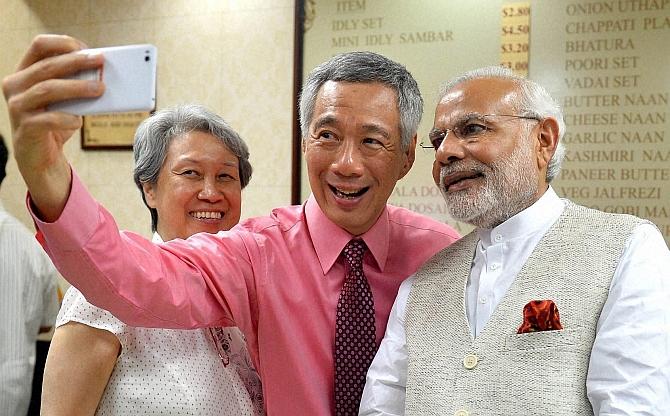

Not only is Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong democratic enough and confident enough to reject the notion of an Opposition-free Singapore, but he is magnanimous enough formally to acknowledge Pritam as Leader of the Opposition.

I knew Pritam when we were both Fellows of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies when I was interviewing Lee's father, creator of modern Singapore, to write Looking East to Look West: Lee Kuan Yew's Mission India.

Generations overlap, and, later, Pritam and my son Deep were both doing their post-graduate studies at King's College, London, and staying at Goodenough Hall in Bloomsbury.

I shall never cease to regret that although I was in Singapore during his lifetime, I did not take the trouble of calling on David Marshall, the first chief minister, and founder in 1957 of the Workers Party.

It was only when sifting through his archival papers and talking to his English widow, Jean Mary Gray, that I realised what an opportunity I had missed.

It's not generally known that Singapore's honeymoon with India began with Marshall, a Baghdadi Jew with Indian connections who made no secret of his tremendous respect and admiration for Jawaharlal Nehru.

But I did get to know, albeit slightly, Singapore's first Opposition MP, the Workers Party's flamboyant yet tragic Jaffna-born J B Jeyaretnam, who was called to the Bar from my grandfather's Inn of Court, Grays, in London.

Hounded with one libel case after another, forced to sell his law books to pay legal debts, driven into bankruptcy, JB was a prickly, almost cantankerous, man.

He gave me a lecture once on barristers not advertising because I had asked for his card.

He must have noticed that successive Indian high commissioners gave him the widest possible berth at diplomatic events.

Seeing him at a Russian reception once, the Malaysian first secretary told me with deep regret that Kuala Lumpur's delicate relations with Singapore didn't permit the Malaysians to invite JB to their functions.

Jeyaretnam had a lively mind.

He knew his law and was intensely interested in the Indian Supreme Court's ban on Parliament tampering with the Constitution's basic features.

He was also the only Singaporean who could stand up to Lee Kuan Yew in debate and give as good as he got.

Sycophantic Singaporeans mockingly repeated Lee's old jibe that he sounded like a stuck gramophone record.

I once saw Lee himself ostentatiously making a great show of reading The Straits Times newspaper all through JB's speech in parliament with the speaker saying nary a word.

Some joked that when JB died, the ruling People's Action Party would make an offer he couldn't refuse to his son, Philip, a successful lawyer and author of Raffles Place Ragtime, a delightful and incisive novel on Singapore life.

Despite it all, JB's scowling features and wispy whiskers were not to be derided.

Over a thousand mourners attended his funeral.

Lee Hsien Loong could have said that the Workers Party's 10 seats (50.49 per cent of the vote) did not entitle its head to the formal dignity of Leader of the Opposition.

He could have used the PAP's 83 seats (61.24 per cent) to continue a single-party dictatorship under parliamentary camouflage.

Instead, he wisely recognised that diversity is of the essence of democracy and that the stronger the ruling party, the greater its responsibility for laying the foundations of a permanent structure of consensual governance.

As Leader of the Opposition, Pritam is assured of the appropriate manpower support and resources to sustain his parliamentary role.

The Opposition has been decimated in India, but the Congress did improve its position from 44 in 2014 to 52 in today's Lok Sabha.

That leaves it only three members short of the stipulated 55 to be the recognised Opposition.

With his appreciation of the spirit of the parliamentary system, his freedom from jealousy and ability to think of future stability, Lee Hsien Loong would not have allowed a technical objection like that to stand in the way of creating a balanced parliamentary equation.

His father told me he used to look to India, especially the writings of Nehru and Sardar Panikkar, for guidance on governance.

It's ironic that India should have so much to learn of the spirit of democracy from his son.

Feature Production: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025