Pakistan must be deleted once and for all from the vocabulary of Kashmir-related negotiations with a finality that is irrevocable, asserts Vivek Gumaste.

In the tense, volatile and fluctuating political milieu of a troubled region like Kashmir, any attempt at reconciliation between discordant political factions, however incipient it maybe, is a cause for optimism: A hope for stability, prosperity and a return to normalcy.

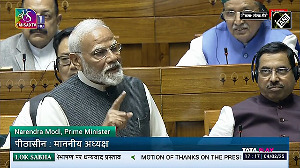

Therefore, the meeting among 14 political leaders of Jammu and Kashmir with Prime Minister Narendra Modi on June 24, the first such since the abrogation of Article 370, is a noteworthy gesture that needs to be lauded.

However, for this interaction to be fruitful, negotiations must occur within the framework of the new reality: A reality that must decisively bury the unholy past and look hopefully towards a bright and honest future.

The first ground rule of this altered new reality is that the abrogation of Article 370 is a done deal: Permanently sealed and stamped with little chance of retraction.

The abrogation of Article 370 was a monumental, historic and seminal decision in the narrative of modern India; a moral rectification long overdue that eradicated the unacceptable barrier of separation that existed in a sea of religious, ethnic and linguistic equality.

Article 370 violated the basic right to equality guaranteed to all Indians by our Constitution. It was an anomaly that allowed political dispensations in the Kashmir Valley to diminish our sovereignty and somehow persuade Kashmiris and the world at large that Pakistan had a say in the affairs of our country.

It was an anomaly that was exploited by the Muslim majority state to establish a religious apartheid that culminated in the ethnic cleansing of over a quarter million Kashmiri Hindus.

That these current talks were initiated on June 24, a day after the 68th death anniversary of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, is of profound significance. The erstwhile leader died in custody in Kashmir in 1953 agitating against Article 370 and in support of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's core principle 'Ek desh mein do vidhan, do pradhan aur do nishan nahi chalenge (There cannot be two constitutions, two prime ministers, and two national emblems in one nation).'

The message at this juncture is clear: There is no place in a modern democracy for a morally challenged, logically invalid and discriminatory statute like Article 370. There cannot and will not be any compromise vis-à-vis Article 370. The sooner the politicians of the Kashmir Valley accept this reality, the better for all.

The next step in this rapprochement process is the question of trust. Trust deficit is the cliched mantra repeated ad nauseum with regard to the Kashmir imbroglio by both politicians and columnists alike, with the implication that the onus for resolving the crisis rests entirely with the government.

This is a simplistic, superficial and erroneous interpretation of the situation. It is naive to believe that the Center-state distrust is the sole driver of the current impasse. The distrust is multilayered and bilateral.

At the heart of the Kashmir problem is a deep-seated and existential distrust that exists at the societal level between the Muslim majority and Hindu minority of J-K; a breach of faith that negates the very concept of India as a secular pluralistic nation and one which has been deliberately overlooked.

The ethnic cleansing of a quarter million Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley is textbook definition of brute majoritarianism craftily masked by calls for autonomy from a predominantly Hindu India; the basic depravity of this act cannot be mitigated by any so-called extenuating factor.

Over the last seven decades Muslim attitudes in the state have failed to instill any confidence in the Hindu community. All chief ministers of J-K since independence have been Muslims despite Hindus constituting at least 30 percent of the population.

Kashmiri civil society must demonstrate that it is willing to change and accommodate the Hindu community.

At the political level, the political leadership of the Kashmir Valley has exhibited a degree of good sense by not insisting on the restoration of Article 370 as a precondition for talks with the government. But they need to do more to burnish their credentials: Pakistan must be deleted once and for all from the vocabulary of Kashmir-related negotiations with a finality that is irrevocable. Pakistan must never again be invoked in discussions.

On its part, the Centre has done its duty by taking the first step. The Centre has always been committed to restoring statehood to J-K and the PM reiterated this commitment in the recent meeting as well. As per the government's plan, delimitation, assembly elections and statehood will follow -- in that order.

Stressing on urgency, the PM remarked: 'Delimitation has to happen at a quick pace so that polls can happen and J-K gets an elected government that gives strength to its development trajectory.'

Delimitation is a process whereby electoral constituencies are redrawn to reflect the changing population so as to ensure equal representations to equal segments of the population. In some countries geographical area is also taken into consideration, prompting Jammu-based parties to ask for the same. Jammu accounts for 62 per cent of the state.

The reason for J-K being subject to delimitation at this time is two-fold: one, J-K did not undergo delimitation in 2008 along with the rest of India, and second, the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act 2019 increased the number of assembly seats from 107 to 114 -- making delimitation a necessity.

The delimitation process cannot be complete or fair if the rights of Kashmiri Pandits living in exile are not taken into account. Until such time they are rehabilitated in the Valley with dignity and security, they must be assured of representation in the new assembly and Lok Sabha. Using the criteria of roughly 145,000 to 150,000 voters per constituency, they would qualify for at least two dedicated seats in the assembly.

A note of caution: The mindset that exists in the Kashmir Valley has evolved over nearly 70 years and will not disappear overnight. It may take years or even decades, but that goal can be attained with sustained persuasion.

A year or two is too short a time to assess the impact of abrogation of Article 370. The central government must not be blink or compromise its principles in its haste to move the peace process forward quickly.

If the politicians from the Valley are not willing to play ball, then the status quo must be allowed to prevail for some more time. Heavens will not fall if J-K is subject to electoral limbo for a few years more.

What is crucial in the long run is that the democratic and secular principles of our country in accordance with our Constitution prevail in J-K without extraneous interference so that growth and development can occur.

After the meeting, PM Modi said, 'Today's meeting with political leaders from Jammu and Kashmir is an important step in the ongoing efforts towards a developed and progressive J-K, where all-round growth is furthered... Our democracy's biggest strength is the ability to sit across a table and exchange views. I told the leaders of J-K that it is the people, specially the youth, who have to provide political leadership to J-K, and ensure their aspirations are duly fulfilled.'

To attain the objectives outlined by the PM, it is imperative that the political leadership of the Valley and the predominantly Muslim civil society of Kashmir introspect deeply, alter its parochial ways, refrain from trifling with our sovereignty and be in sync with the rest of India with regard to democratic and secular principles.

That alone is the way forward to the Kashmir conflict.

Academic Vivek Gumaste, who is based in the United States, is the author of My India: Musings of a Patriot. You can e-mail the author at gumastev@yahoo.com

© 2025

© 2025