'Both Japan and China face a common challenge: How to deal with Trump.'

The trade war with the US seems to have facilitated/hastened Abe's China visit, the first by a Japanese prime minister since 2011,' points out Dr Rajaram Panda.

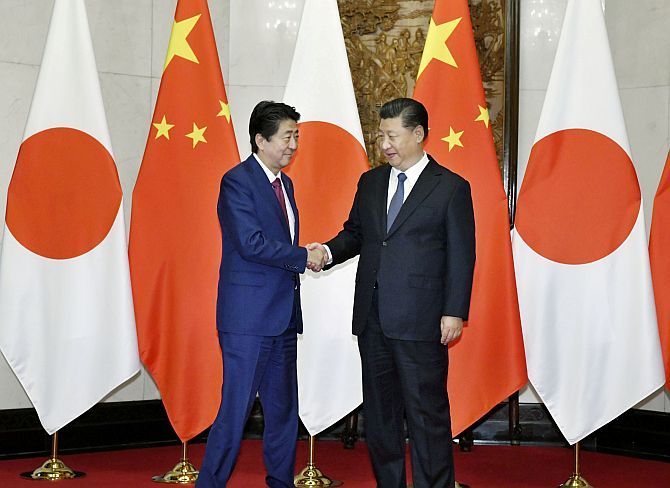

It was the first visit by a Japanese prime minister to China in seven years. Photograph: Kyodo via Reuters

Northeast Asia is witnessing an interesting geopolitical churning with leaders of each country trying to reach out to the other to address bilateral and regional challenges confronting them.

The political situation has emerged conducive to conduct such high-level diplomacy.

The new situation that was ushered with the dawn of the New Year has been dramatically different from the preceding year when the diatribe and vitriolic exchange of words between US President Donald J Trump and North Korea's Kim Jong Un raised the spectre of a major regional conflict with potential to assume a global dimension.

The first in a series of summit diplomacy was between Moon Jae-in, the South Korean president, and Kim Jong Un in April 2018 followed by two summits in succession.

Then was the big event, a summit between Trump and Kim in Singapore in June 2018, with talks now for another summit, the dates and venue of which remain undecided.

At a time when leaders are engaged to address North Korea's nuclear and missile issue, Japan, a potential adversary in a possible conflict situation centering in the Korean peninsula, is reaching out to China, North Korea's main benefactor.

Japan's Prime Minister Abe Shinzo is also trying to mend fences with Russia, reaching out to President Vladimir Putin to resolve territorial disputes and sign a peace treaty with Russia.

In this matrix of power relations and issues creating conflictual relationships, Abe's tasks are cut out.

Seen one way, Japan sits in a vital position to address these issues and provides Abe a huge challenge as well as opportunity to demonstrate his leadership to the region and the world.

Against this background, Abe's visit to China and summit diplomacy with Chinese President Xi Jinping, immediately followed by Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi's visit to Japan, needs critical analysis.

With a view to mend fences between the two traditional rivals, Abe made a rare visit to Beijing on October 23, 2018 with the hope to improve relations and seek new vistas for economic partnerships and common ground in the wake of both nations coming under US pressure on trade.

Trump has levied tariffs on imports both from Japan and China with a view to correct the trade imbalance.

It was an opportunity for Abe and Xi to discuss how to cope with this new challenge thrown up by Trump.

Since both sides are on the same side on the trade issue, if Japan leans away from the US because of decreased economic opportunities, the prospects of both Japan and China getting closer would be enhanced.

The trade war with the US seems to have facilitated/hastened Abe's China visit, the first by a Japanese prime minister since 2011.

Though Abe visited China in 2016 to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Beijing, this visit was the first formal journey to the Middle Kingdom by a Japanese prime minister in seven years.

The timing of Abe's visit is significant as October 23 marked the 40th anniversary of the Treaty of Japan-China Peace and Friendship that took effect in 1978, and follows Prime Minister Li Keqiang's visit to Japan in May 2018 for a three-way summit among Japan, China and South Korea.

The bilateral accord was described by then Japanese prime minister Takeo Fukuda as 'an iron bridge that evolved from a suspension bridge.'

The 1972 joint communique that established diplomatic ties between Tokyo and Beijing was thus strengthened into a full treaty.

With Abe's visit, the two sides are poised to develop their relations further.

Abe's visit was part of a long process to repair ties in the wake of a disastrous falling out in 2012, when Tokyo 'nationalised' disputed islands claimed by Beijing.

The incident prompted anti-Japanese riots in China and kicked off a frosty spell that has only gradually and recently begun to thaw.

A chance encounter between Abe and Xi on the sidelines of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok in September paved the way for ministerial visits by both sides and a softening of rhetoric.

Indeed, Abe's Beijing visit provided a 'historic opportunity' to work on multifarious bilateral issues.

Xi observed this opportunity to make 'a new historic orientation for the development of Sino-Japanese relations'.

Abe reciprocated Xi's desire by expressing to switch relations from 'competition to collaboration.'

The Abe-Xi bonhomie is being interpreted by analysts as an attempt to hedge the risks thrown by Trump. Such an interpretation stems from the fact that both focused on cooperation on trade and avoided the issue of disputes over islands in East China Sea.

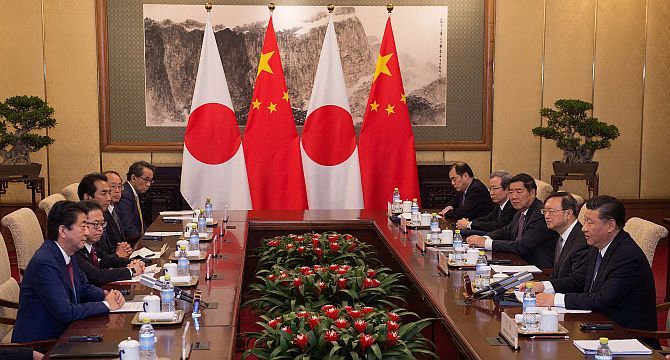

Abe was accompanied by around 500 Japanese business leaders. Both leaders signed a dozen deals including a currency swap worth $30.29 billion effective until 2021.

The pacts were reached as both nations looked to carve out new areas of cooperation and seek ways to promote trust which has been fragile at times after diplomatic relations resumed in 1972.

Deals worth $18 billion signed between Chinese and Japanese companies reflected the 'bright prospects' for cooperation between the two countries.

A deal towards establishing a yuan clearing bank was also inked.

The revival of a currency swap arrangement with a new currency pact after a four-year hiatus between the Bank of Japan and the People's Bank of China will allow the yen to be swapped for the yuan and vice versa in times of a financial crisis and keep the financial system stable.

The previous pact, concluded in 2002, expired in 2013 after deterioration in bilateral relations due to tensions over the Senkaku Islands.

With momentum gathering for improvement in relations, both sides agreed to study reviving the currency pact when Premier Li visited Japan in May.

The central banks of both Japan and China also exchanged memoranda of understanding to exchange information on the establishment in Japan of a yuan clearinghouse, which settles the Chinese currency-denominated transactions outside China.

The moot point to boost economic ties followed the Sino-US standoff over tariff issues as both Abe and Xi resolved to safeguard long-term healthy and stable bilateral ties.

The tit-for-tat tariff battle between the US and China can have serious implications for Japan, which Abe wanted to address in his talks with Xi.

An agreement to boost cooperation in the securities markets including the listing of exchange-trade funds and facilitate smoother customs clearance was another highlight of the more than 50 deals and agreements signed between the two Asian neighbours.

Abe and Xi agreed that both sides should accelerate talks on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and on a China-Japan-Korea trade zone.

The RCEP is a free trade agreement proposed by China with Southeast Asia and various countries on the Pacific Rim including Japan.

The Belt and Road Initiative has been Xi's pet project and obviously this figured prominently in the Abe-Xi talks.

Abe signaled some interest in the BRI, which funds major infrastructure works.

While Japanese business is keen to have increased access to China's massive market, Beijing is interested in Japanese technology and corporate knowhow.

Since both are complementary economies, they can derive mutual dividends by deepening trade and investment ties.

Japanese firms -- including big auto companies like Toyota -- are excited that improvement in ties with China can help them compete with their US and European rivals in that country.

On its part, Beijing expects Tokyo to endorse its ambitious BRI programme, an initiative that Xi hopes will further boost trade and transport links with other countries.

The government of Japan needs to remain circumspect, but should back its private sector and let the companies make their own decisions.

It is too risky for the State to get involved too far.

Japanese companies can accumulate experience on how to deal with the BRI as they cooperate with companies from other countries.

Denuclearisation of the Korean peninsula also figured in the Abe-Xi discussion.

This probably influenced both leaders to undertake a more in-depth strategic dialogue. The mutual threat perception that bedeviled Sino-Japanese ties was relegated to the backburner.

Abe informed Xi of Japan's determination to normalise diplomatic relations with North Korea, but only if preconditions were met, including denuclearisation and the release of kidnapped Japanese citizens.

Abe was trying to send China a message that it is the responsibility of both countries to work towards maintaining peace and stability in the region.

An invitation by Abe to Xi to visit Japan in 2019 could materialise soon. Xi has promised to 'seriously consider' the invitation.

However, territorial issues are unlikely to go away so soon.

In fact, days before Abe's trip, Tokyo lodged an official complaint after Chinese ships cruised around the disputed islands that Tokyo calls the Senkaku and Beijing labels the Diaoyu islands.

In September, Japan conducted its first submarine drills in the disputed South China Sea.

Though Japan has no claims on this oceanic space, it has expressed concern about Chinese military activities in the South China Sea.

When Abe returned to power in his second stint as prime minister in 2012, Sino-Japanese ties were at its nadir because of the feud over the East China Sea islands and the territorial dispute, which was a key source of friction between the two countries.

Despite a host of economic deals, Abe was categorical in telling his counterpart Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang that there would be 'no genuine improvement' in bilateral ties unless there was 'stability in the East China Sea'.

Abe's position is tricky.

While worried about China's growing naval power, his keenness to build close economic ties with Japan's biggest trading partner has merit.

However, Abe faces the difficult task to balance Japan's rapprochement with China without upsetting Japan's key security ally, the US, with which it has trade problems of its own.

Seen differently, the sudden chill in China's relations with the US over trade issues meant China was looking for friends and Abe seized the opportunity and use it to nudge XI toward policies that support global norms of economic and diplomatic cooperation.

On the surface, it appeared Abe scored the first round with a series of economic deals and if implemented sincerely, both would benefit as also the rest of the world.

Both Japan and China face a common challenge: How to deal with Trump.

While China faces a wall of US tariffs and responded with retaliatory measures, Japan has also been bullied by the Trump administration in a smaller way, forcing it into bilateral trade talks, scheduled to begin in January 2019.

Thus, a new situation emerges where two historical rivals -- Japan and China -- seek influence across Asia to checkmate a power -- the US -- that is disrupting the established world order.

This new situation presents China an opportunity to seek a special ally in Japan.

If Abe and Xi remain sincere in their commitments to what they resolved to address during Abe's visit, their standing as world statesman would have received a boost.

Dr Rajaram Panda is a Lok Sabha Research Fellow, Parliament of India, New Delhi.

© 2025

© 2025