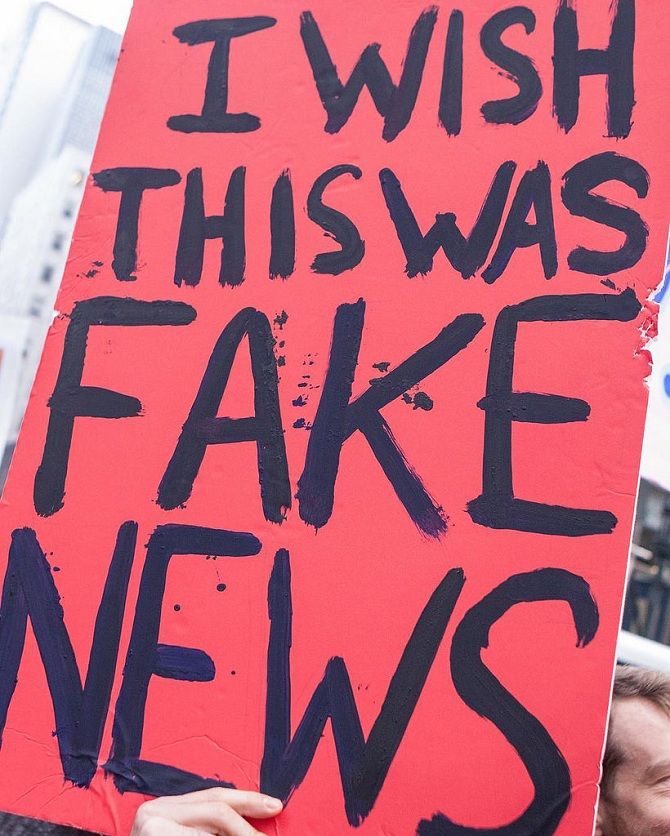

And since social media platforms benefit from it, shouldn't they be held responsible for the hate and fake news they spread, asks Vanita Kohli-Khandekar.

Should technology companies and platforms be responsible for the hate and fake news they spread?

If you spend 30 minutes on Twitter you are bound to get upset about something or the other.

There are comments that incite people to violence by members of Parliament and even ministers, at times.

There are obscene, abusive comments suggesting violence, especially against female journalists.

On Facebook, every few days a friend or a colleague expresses visceral dislike, advocates or condones violence and abuse of other human beings in the name of religion or nationalism.

And this is not just in India. People around the world seem to be swimming in hatred and bile.

You could argue that hatred and conflict have been part of human evolution, so how can technology or social media be held responsible. Because just like mass media, social media, too, has the power to amplify a message.

The big difference is that mass media is governed by laws of defamation, libel and other acts that restrain it from abusing its power to amplify. There is largely nothing that stops someone from creating a completely fake factoid on, say, Jawaharlal Nehru and circulating it via WhatsApp, Twitter or Facebook. Many of the cases of lynching, some of the riots and conflicts that have happened in India recently have turned out to be a result of a fake video or WhatsApp message.

If Star, Zee, NDTV or The Indian Express among others are subject to press laws, should Google, WhatsApp and the others be, too?

This is the first point to consider on the question this column asks.

The second is whether platforms and tech firms should edit content.

"The internet is the First Amendment (under the US Constitution) come to life," reckons Jeff Jarvis, a New York-based journalism professor and proponent of an open web.

"With free speech comes bad speech. Free speech also includes the right to edit. However, Twitter's value is its openness and that is why they would not want to edit. It is up to us to develop norms of civility if we don't want them to edit," points out Jarvis.

He is right -- free speech and privacy both become victims in any attempt to regulate the internet or the platforms that dominate it.

However, Google, Facebook or Twitter actively monetise what we post or forward. And they do it very well. Google (under its holding company Alphabet) is the largest media owner in the world, with $79.4 billion in ad revenues in 2016, says a Zenith Media report. Facebook is the second largest.

There is serious money in the business of lies, and many platforms and creators benefit from it.

A case in point is Jestin Coler, who began writing fake news stories in 2013. Hundreds of (right-wing) websites happily picked these up and spread them around. The handful of sites he had set up, including nationalreport.net, got 100 million page views peddling completely fake stuff on politics et al.

The contributors who were paid through Google AdSense made more money than others in the genre, said Coler in an interview to Nieman Reports. As the owner of Disinfomedia, he made between $10,000 and $30,000 a month.

This is possible because of programmatic advertising software. It places ads based on page views, engagement and metrics that it reads. So, a brand from, say, a Unilever or Procter & Gamble could be on a site selling pirated films or a jihadi speech.

These "bad ads" are now causing huge churn in several markets. In the UK, for instance, members of Parliament are baying for more controls.

Facebook and others have set up serious initiatives to tackle fake news. Maybe something will come of it.

Abhinav Shrivastava, senior associate with the law offices of Nandan Kamath in Bengaluru, thinks that this setting up of voluntary controls is the best way to balance the conflicting interests of free speech, an open internet with less hate and lies. Maybe.

But there still remains one more philosophical question: If technology simply enabled hate that was already there, what will it take for humanity to let it go?

© 2025

© 2025