A man with a grandfatherly moustache, another in saintly robes and reportage on the saffron face of terror that went unnoticed, says Bharat Bhushan.

A man with a grandfatherly moustache, another in saintly robes and reportage on the saffron face of terror that went unnoticed, says Bharat Bhushan.

Does the police have a stereotype of a terrorist, a militant or a murderer? The face of Islam’s "rage boy" Shakeel Ahmed Butt, with straggly beard, screaming mouth and enraged eyes has been featured on the pages of both Indian and international newspapers. He has been routinely held by the police in the last five years in Jammu and Kashmir.

Innocent Muslim youngsters are rounded up after every terrorist attack, others are "found" with Maoist literature, allowing the police to pack them away as hard-boiled insurrectionists. The State identifies its terrorists and deals with them firmly, so that we can sleep peacefully at night.

But what has happened to its zeal after the allegations of terrorism against the chief of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Singh’s Mohan Bhagwat by a fellow RSS full-time worker? Would they be as quick to stick a label or verify the charges against a man with a grandfatherly moustache by another in saintly robes?

But for sporadic media mention, a remarkable investigative report about Hindutva terror has gone virtually unnoticed by the government. The report in The Caravan magazine* claims that Bhagwat and another top RSS functionary, Indresh Kumar, were part of a terrorist conspiracy against Muslims.

Bhagwat, as the then general secretary of the RSS sanctioning the terrorist attacks, cautioned Aseemanand, ‘It is very important that it be done. But you should not link it to the Sangh.’ In July 2005, Bhagwat and Indresh Kumar met Aseemanand along with another terror accused Sunil Joshi (since murdered) at Surat where terrorist strikes against "Muslim targets" were discussed. Sanctioning the strikes, Indresh Kumar apparently told Aseemanand, ‘You can work on this with Sunil. We will not be involved, but if you are doing this, then you can consider us to be with you.’

Aseemanand claimed, "'Then they told me, Swamiji, if you do this we will be at ease with it. Nothing wrong will happen then. Criminalisation nahin hoga [it will not be criminalised]. If you do it, then people won't say that we did a crime for the sake of committing a crime. It will be connected to the ideology. This is very important for Hindus. Please do this. You have our blessings.'"

Aseemanand is implicated in five terrorist attacks. He has been charged in the Samjhauta Express attack; Hyderabad's Mecca Masjid blasts; and the Ajmer Sharif bombings. He has been also named in two terrorist attacks in Malegaon. He has admitted to planning the attacks, selecting the targets, providing funds and sheltering those who planted the bombs.

In his confessional statement before a magistrate earlier, Aseemanand had not named Mohan Bhagwat. He had, however, implicated Indresh Kumar for providing material support to the conspirators. After summoning Kumar once for questioning, the police let him go.

One might wonder whether the Aseemanand interviews (recorded for over nine hours) by a journalist can be treated as an extra-judicial confession. On this would hinge whether the government agencies could act on the new information provided. Surprisingly, the RSS and Aseemanand's lawyers have not asked for any forensic tests to determine the authenticity of the recorded conversations.

Normally, a statement made to an independent journalist voluntarily would be admissible in a court of law, unlike statements made to the police. However, since the Ambala Jail where Aseemanand was interviewed is a judicial custody, it would matter whether the journalist had obtained the permission of the court.

It seems that the journalist had not done that. When she first met Aseemanand during one of his court appearances, he apparently suggested that she come as a lawyer since she would get more time to interview him. Yet as she was not Aseemanand's lawyer, there can be no issue that what Aseemanand told her was privileged information, and theoretically it can be admitted in court.

However, for a statement to an independent journalist to be admissible if it will also have to be voluntary, truthful and consistent with the prosecution's story. A statement made in the presence of guards cannot be called voluntary; its truthfulness also needs to be tested; and it does not match the prosecution's story which does not mention Bhagwat. The taking of recording equipment inside the jail is violation of jail rules, but that violation is analytically separate from the confession.

What role then can the interview have in the legal investigation of terrorism?

The journalist had identified herself to Aseemanand, who proposed that she use the ruse of a lawyer to visit him. She disclosed whatever he said because he wanted her to, though his reasons for wanting to do so remain unclear.

An attempt can possibly be made to admit Aseemanand's statement as extra-judicial confession because it is not exculpatory. He is not claiming innocence by blaming others. His plea is that, he along with some others, including Bhagwat and Kumar, planned the terrorist strikes.

Taking the plea to admit the interviews as extra-judicial confession, the government can move the court for a supplementary chargesheet and summon both Bhagwat and Kumar. This may be tricky, however, since Bhagwat and Kumar are not the co-accused of Aseemanand in any of the terror cases. The court may not allow this.

If the court holds that the confession has no evidentiary value, then it cannot be used for further investigations. However, there should be a willingness to test the law on this. The only other way out is to make Aseemanand an approver and get him to give a more detailed statement before the court, so that the alleged terrorist nexus can be exposed.

As of now, little progress seems possible. The manner in which the Congress-led government has handled the Hindutva terror cases suggests that it does not want to turn on the heat on the RSS leadership. It is a pity, therefore, that this excellent reportage on the saffron face of terror will not be used to expose the entire Hindutva terrorism network. In any other civilised society the State would be obliged to do so.

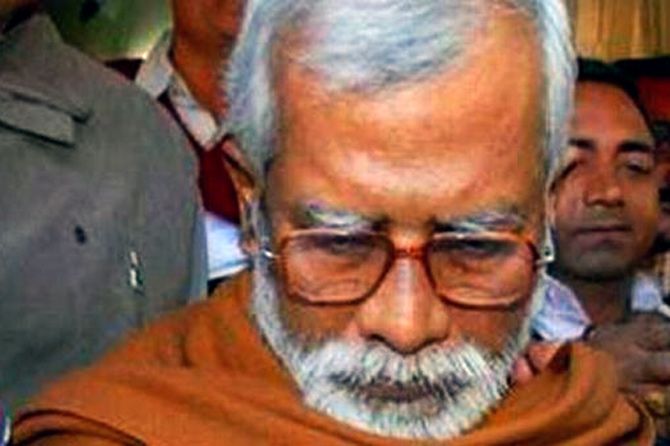

Image: Swami Aseemanand, the terror accused.

© 2025

© 2025