'The sacking of Outlook magazine's Editor-in-Chief Krishna Prasad provides another example of the saffron camp's disrespect for dissent,' argues Amulya Ganguli.

In a speech at the time of the release of the Bharatiya Janata Party's manifesto before the last general election, Narendra Modi, then the presumptive prime minister, had given the assurance that he would never act with bad intentions.

He can be said to have kept his promise so far although why anyone should have pledged himself to above board conduct on his own is intriguing. Did he detect a propensity for wrong-doing in himself?

Even if the prime minister can be largely absolved of any serious transgressions in his two years in office, the same cannot be said of some of his fellow travellers. The antics of the latter in creating an atmosphere of intolerance first led to the flood of awards being returned by their winners, including writers, historians, filmmakers and scientists.

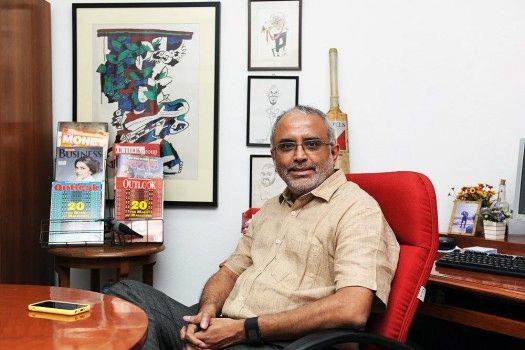

Now, the peremptory sacking of Outlook magazine's Editor-in-Chief Krishna Prasad provides another example of the saffron camp's disrespect for dissent.

It does not take much insight to realise that the editor paid the price for his boldness in publishing a piece about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, the BJP's friend, philosopher and guide, and the hidden power behind the throne, according to common perception.

Since a First Information Report has been filed relating to the article, the powers-that-be could have let the law take its own course, as the cliche goes. But the Modi government and the prime mentor were apparently too impatient. Hence, the wielding of the axe.

As it is, the government's respect for the freedom of the press is known to be virtually non-existent. Otherwise, one of its minions -- Minister of State V K Singh -- would not have been so gleefully talking about 'presstitutes,' a coinage of which the former army chief appears to be inordinately proud.

Modi himself has never held a press conference of the wide-ranging kind which was seen in his predecessor's time. Instead, he has chosen one particular television anchor for an occasional interview to the exclusion of all others.

Evidently, he does not trust himself to be quizzed by media personnel at random in case their inquisitiveness forces him to stage a walkout as during one of Karan Thapar's question-and-answer sessions.

It is also possible that the prime minister does not have satisfactory responses to queries, for instance, about why only saffron apparatchiki were selected as the heads of prestigious institutions like the Indian Council of Historical Research, the National Book Trust, the Film and Television Institute and the Central Board of Film Certification. Nor about the abrupt termination of an editor's tenure.

It will be unfair, however, to blame only the Hindutva camp for believing in unofficial censorship.

The Congress was no less culpable, and not only during the Emergency. It played a part, for instance, in forcing out a former Outlook editor, Vinod Mehta, from the editorship of the Indian Post in Mumbai and later from the same position in Pioneer in Delhi. It is understandable why Mehta named his dog Editor.

That nomenclature may have been too sharp a dig at the office although it has been steadily losing its lustre. First, the owners started taking a close interest in their newspapers before becoming editors themselves as in the Ananda Bazar Patrika group.

Then, the tycoons decided to breathe heavily down the necks of the owners if anything unfavourable to their business interests saw the light of the day and 'persuaded' the proprietors -- with a kind word and a gun, as Al Capone said -- to sack the offending editor.

In addition to the ever present threat of the guillotine hanging over their heads, editors have also seen a steady diminution of their authority by the mushrooming of various editorial posts, which is another weapon in the hands of the owners to cut them down to size.

Not surprisingly, the executive editor's role has been defined as that of executing the editor and of the editorial director as that of directing the editor. An old hand in The Times of India, Dilip Mukherjee, used to describe the profusion of designations as a kind of pollution.

Although salaries of the denizens of the so-called Ivory Tower have risen exponentially in the last 20, 30 years, the shelf life of a once-prestigious post has become shorter. Nor is there any possibility of the good old days of Frank Moraes and Sham Lal returning any time soon.

Amulya Ganguli is a writer on current affairs.

© 2025

© 2025