'Refusing to implement the CAA-NRC, as some states have done via resolutions in state assemblies, is a violation of the Constitution; an attempt to alter the fundamental structure of our democracy and a recipe for anarchy,' argues Vivek Gumaste.

The quality of public discourse in India has plummeted to rock bottom levels, scraping at the very dregs of common sense, basic knowledge and good values.

It is a harangue of incredible ignorance atrociously complemented by an overwhelming dollop of malicious disinformation; a slanging match driven by ideological fixation rather than one based on facts, logic and national interest. A Goebbelsian exercise par excellence that would make even the Nazi propagandist flinch.

Especially disconcerting is the role of supposed intellectuals, who instead of putting a brake on canards by honestly clarifying concerns, resort to spinning their own warped narrative to complete an epitome of ultimate falsehood.

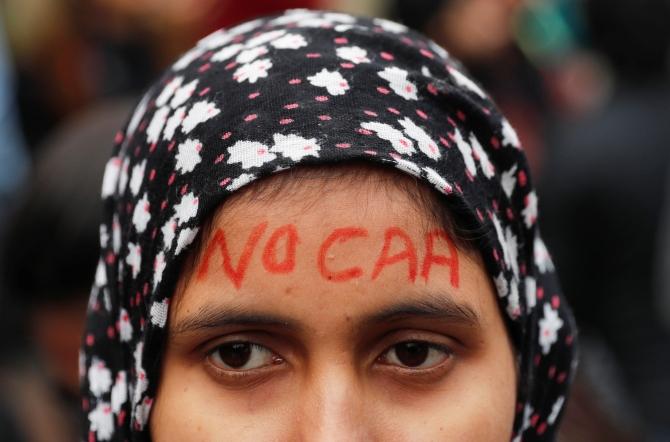

India has been turned into a Land of Folly. Nothing illustrates this tragedy of deception better than the recent high decibel brouhaha over the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the consequent National Register of Citizens.

In order to clear up the overwhelming atmosphere of misconception that has been engendered and popularised by high-pitched violent protests and emotionally charged television anchors, we need to pause and objectively parse out the elements of both the CAA and the NRC; a duty that must befall every right-thinking Indian. I purport to do this by a series of questions.

Are we morally justified in granting accelerated citizenship to Hindus, Sikhs Christians and other minorities from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan?

To answer this question, we need to first define who is a refugee and who is not.

Refugees are defined and protected under international law. The 1951 Refugee Convention is a key legal document and defines a refugee as: 'Someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.'

With this clear definition, let us look specifically at the three countries -- Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh -- mentioned in the Citizenship (Amendment) Act as to who would be defined as a refugee from the above-mentioned countries.

Article 1 of the Pakistan constitution states that, 'Pakistan shall be a Federal Republic to be known as the Islamic Republic of Pakistan' while Article 2 stipulates that Islam will be the State religion.

The Bangladesh constitution has an Islamic invocation placed above the preamble and Article 2A states that the 'State religion of the Republic is Islam'.

Similarly, Afghanistan has an explicitly Islamic preamble to its constitution and Article 1 states that 'Afghanistan shall be an Islamic Republic'. Article 2 further clarifies that the 'sacred religion of Islam is the religion of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan'.

Despite protestations in these respective constitutions that others can practise their religion freely, the existence of a State religion effectively relegates all other religions to a secondary status, leaving them open to harassment and discrimination: A fact borne out by recent history specific to these countries.

A constitutionally sanctioned second-class religious status coupled with a history of repression make Hindus, Sikhs, Christians and Buddhists and other minorities from these countries fit the definition of refugees as defined by the 1951 Refugee Convention -- elements that the CAA incorporates, making it a justifiable proposition.

The issue of Ahmediyas interjected into the current debate is of nuisance value intended to obfuscate the debate and not a valid argument for several reasons.

One, the CAA refers only to religions and not sects (India considers Ahmadis (external link) as Muslim).

Second, Ahmadiyas while safe in India continue to be ostracised and persecuted by Muslims in India -- they are not represented on the All India Muslim Personal Law Board and normally seek better pastures in other countries, namely the UK, Germany and Canada.

Thirdly, the actual number of Ahmadiyas seeking refuge in India is too small to merit mention in the CAA.

Having said that, it must be emphasised that individuals from these countries belonging to religions not mentioned in the CAA can avail of other avenues to officially seek refuge in India -- a provision that has been intentionally ignored by the anti-CAA arguments.

Muslims by and large from these countries who have illegally entered India do not fit the UNHCR definition of refugees and cannot be treated on par with Hindus, Sikhs and Christians fleeing persecution.

Therefore, to claim that the CAA discriminates against Muslims is facetious.

Such a contention is akin to equating a poor labourer's child and a millionaire's offspring with regards to financial subsidy in education: An absurd proposition that makes a mockery of common sense.

Interjecting a purist definition of equality devoid of extenuating circumstances as the CAA-NRC protests attempt to do is a dangerous precedent that would call into question all affirmative action projects including Dalit enhancement and special privileges and fiscal aid doled out to minorities in India.

Is opposition to the NRC a negation of our Constitution?

A nation-State is not a chaotic free-for-all with open access to anyone and everyone. It is a defined political entity stipulated by norms that guide its ideological character, demarcate its physical boundaries and which certify who is an inhabitant of the State and who is not; all clearly laid down in the Constitution in black and white.

Articles 5-11 of the Indian Constitution clearly mandates who is and who is not a citizen of India. Several amendments to the Constitution over the years have refined the criteria for citizenship, notably the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2003 which defined who is an illegal immigrant and disallowed citizenship to children of illegal immigrants.

But these Constitutional stipulations would be meaningless if there was no system to implement these requirements. Therefore, the CAA 2003 mandated the Government of India to construct and maintain a national register of citizens.

Every sovereign nation needs to have a mechanism to differentiate between valid citizens and illegal entrants and every sovereign nation has one except India.

However, strictly speaking, the NRC is not a new concept; it has been on the books since the 1950s. In order to implement the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950, which came into effect on March 1, 1950, and which mandated the expulsion of illegal immigrants from the state of Assam, an NRC was prepared for the state in 1951 after the conduct of the national census.

The recent NRC update (Assam) completed in 2019 (external link) was a Supreme Court sanctioned exercise in accordance with the Constitution of India.

The NRC is a Constitutional directive. So, one must realise that those opposing the NRC are in effect opposing the Constitution even though they may attempt to obfuscate this reality by flaunting the Constitution and by their raucous vocality; they are defiling the same Constitution that they claim to uphold. Let us not get carried away.

The functioning of a federal democracy is contingent on smooth coordination between the Centre and states. Conferring citizenship is the exclusive prerogative of the Centre and falls under the Union List of the 7th Schedule of the Constitution.

Refusing to implement the CAA-NRC, as some states have done via resolutions in state assemblies, is an egregious violation of the Constitution; an attempt to alter the fundamental structure of our democracy and a recipe for anarchy.

This is a dangerous precedent of gargantuan magnitude that poses the greatest threat to our democracy post 1975.

Academic Vivek Gumaste, who is based in the United States, is the author of My India: Musings of a Patriot. You can e-mail the author at gurhastev@yahoo.com

© 2025

© 2025