'When I told my wife I was going to ask our daughter-in-law if she was planning on hitting the streets, my wife took me aside and whispered fiercely in my ear, "Don't let her learn the language of dissent because it'll come back to bite us",' says Kishore Singh.

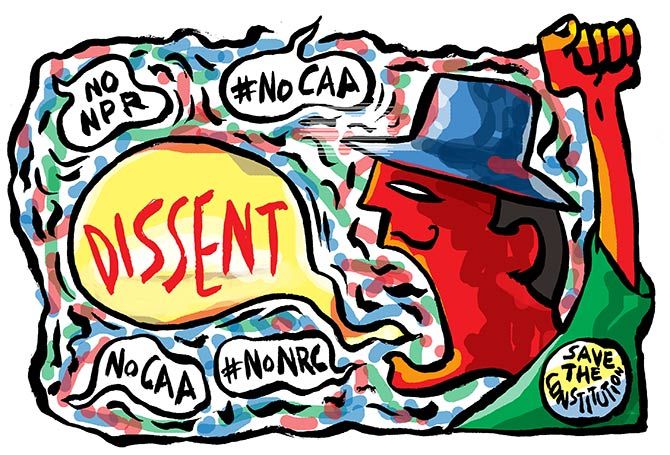

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

When my daughter said she'd like to participate in the pro-citizenship protests sweeping across the capital, I couldn't help feeling triumphant at having raised an upright, civic-minded, child.

Friends, children of friends and colleagues had taken leave of absence to register their solidarity with the protesters.

"I really admire them," my daughter said wistfully, so I checked my messages to draw up a list of places where the marchers were gathering.

She could have the car and driver, I suggested, as news of metro stations being shut down came in.

"What for?" my daughter asked. "So you can be dropped at a point close to Jantar Mantar," I said, having heard from a friend how she had been forced into a bus at Mandi House.

"I respect their spirit, I really do," my daughter reiterated, "but it's so cold outside, I'll stay in today."

Adding, "Could you ask Mary didi to give me breakfast in bed, please?"

While our daughter was having her breakfast, my wife was fretting about her plans for the weekend. She'd invited a host of her friends and acquaintances to an open house lasting two days, and thought the blockage of the roads inconvenient and cavalier.

"How am I to order supplies?" she fumed.

"How tiresome of everyone to choose to demonstrate when I am hosting a gathering." I pointed out that the movement was spontaneous and perhaps she should cancel her event seeing how it violated the spirit of collective dissent we were witnessing.

"I don't understand all this politics-sholitics," my wife demurred, "so I'm going to have my party anyway."

My son, I hoped, would spare some time to show support for his friends, and ours, in the melee of campaigners, but he had other ideas that didn't include shouting slogans, or passing rosebuds to policemen.

He's been predisposed to avoiding anything that appears even remotely confrontational, preferring to lay down arms than get into a war of words -- which is strange for a lawyer.

"I'm an interlocutor," he explained, when I expressed my disapproval at this lack of interconnectedness, "I can help resolve any issue between two or more parties, but I can't appear to take sides, or a stand."

"You understand, don't you?" I didn't, actually, but not wanting to appear a stuffy, old coot from another generation, I let it go, and my son worked out a route that he and his biking buddies could take to give their sports bikes an airing.

When I told my wife I was going to ask our daughter-in-law if she was planning on hitting the streets, my wife took me aside and whispered fiercely in my ear, "Don't let her learn the language of dissent because it'll come back to bite us."

I told her I didn't understand why, so she explained, "If you teach her to shout slogans and raise her hands, then she'll need somewhere to practice. What if she complains about you or me to our children, and the staff -- what will we do then?"

"But you," she said, "It's all right for you to go to India Gate, or wherever, and be part of the protests."

"Me," I balked, "I can't do that, not when I've got a batch of new books that I plan to devote the weekend to reading."

© 2025

© 2025