'India's parliamentary democracy is ridden with flaws,' argues Rajeev Srinivasan. 'Parliament has become a monarchy, with seats captured by a strongman, and then inherited by his wife or children.'

Earlier in our series celebrating 60 years of the first joint session of Parliament:Aakar Patel: Parliament's role in making India a great nation is over

Subhash Kashyap: People feel that for our MPs the nation comes last

Arvind Kejriwal: MPs are bonded labor of their parties

Shashi Shekhar: Nothing diminishes the fact that we are a Great Nation

On the 60th anniversary of the first joint session of Parliament, Rediff kindly requested me to write about it. I wish I could, in the spirit of celebration and all that, say something nice about this august body. But, unfortunately, I can only give it a grade of D+ for results. In fact, I fear it is actually worse.

I used to think -- like many others -- that politicians are imbeciles. I have changed my mind: They are the smartest people in the country; and some of them may have figured out that being in Parliament is the quickest and easiest way to massive riches.

Indians are good at the form, but not the substance, of many institutions. In fact, India is not a democracy as the dictionary defines the term. In reality, it is probably a kakistocracy, rule by the very worst possible people.

This is particularly sad in that we had working democratic systems very long ago: The Uttaramerur inscriptions in Tamil Nadu show in detail how a self-governing village entity should run itself: Please see a report in DNA (external link) and a note (external link) from the Tamil Nadu Election Commission. They specified clearly how to elect officials, and also how to punish them in case they erred.

Where did all this go wrong?

According to the above Election Commission note, it was because British imperialists destroyed the decentralised political system of local government, no doubt because they could exploit people more with a centralised system. After Independence, the new rulers decided that they liked the status quo ante. Can't blame them, really: Who doesn't like to squeeze money out of, and lord it over, the masses?

India's parliamentary democracy is ridden with flaws. First is nepotism. Parliament has become a monarchy, with seats captured by a strongman, and then inherited by his wife or children. There is even the strange term 'pocket borough' for this phenomenon. It is, for all practical purposes, indistinguishable from the fiefdoms of the princely states of old -- which were, according to conventional wisdom, dissolute and abhorrent. At least the old kings had a sense of noblesse oblige, which the modern-day ones lack.

Patrick French did a piece (external link) in Outlook titled 'The Princely State of India' wherein he shows this interesting statistic about the hereditariness of members of Parliament, based on party:

Rashtriya Lok Dal 100 per cent (5 out of 5)

Nationalist Congress Party77.8 per cent (7 out of 9)

Biju Janata Dal 42.9 per cent (6 out of 14)

Congress party 37.5 per cent (78 out of 208)

Bahujan Samaj Party 33.3 per cent (7 out of 21)

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 33.3 per cent (6 out of 18)

Samajwadi Party 27.3 per cent (6 out of 22)

Communist Party of India-Marxist 25 per cent (4 out of 16)

Janata Dal-United 20 per cent (4 out of 20)

Bharatiya Janata Party 19 per cent (22 out of 116)

Trinamool Congress 15.8 per cent (3 out of 19)

Shiv Sena 9.1 per cent (1 out of 11)

All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam 0 per cent (0 out of 9)

Telugu Desam Party 0 per cent (0 out of 6)

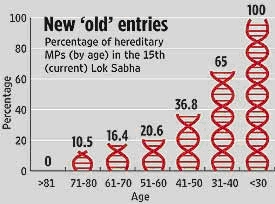

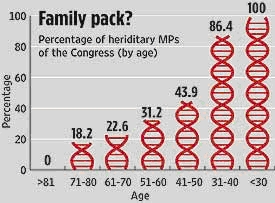

Furthermore, there are two charts from the same article that show how the youngest MPs are totally hereditary; and how it is even more true for the Congress than for others:

Source: Outlook magazine

The second issue is corruption. With stalwarts such as A Raja and Suresh Kalmadi in Parliament (and lately guests of Tihar jail), I suppose there is no need to belabour the point. It has become a fact that if you are rich, thuggish (ruthlessness and violence can get you votes) and unscrupulous, you become a better politician in India.

Surely corruption -- often on a large scale -- is part and parcel of every democracy. We have seen this in other countries; and it is a corollary of the fact that it costs an enormous amount of money to contest (or buy) an election. An intrepid chief election commissioner once tried to reduce the cost of elections, but his efforts were in vain. So what's a politician to do? Obviously raise the funds from various 'friends', who will eventually call in their chips, which of course is the rentier function of political office.

There is a way of dealing with this -- and that would be for the State to fund elections in addition to policing the ceiling on spending vigorously. However, I suspect that would be a non-starter in India.

Third, the Indian system has foolishly included nihilists who completely reject the very idea of a Constitutional democracy, and believe that power, simply, flows from the barrel of a gun. These people have their own warped definition of democracy: 'One man, one vote, one time'. That is, if you vote them in once, they will never leave.

One of these people was the speaker some time ago, whose office is supposed to be neutral and impartial. When members of a party he did not like were caught in a misdemeanour (they were found to have taken money to ask certain questions), he immediately dismissed them. Fair enough.

However, when there was a far more serious charge -- that members of a party had paid huge sums to MPs of other parties in a crucial no-confidence motion -- he took no action. Further, when asked by his own party to vote on an issue, he refused, because he apparently couldn't bear to be on the same side as another party he detested. Neutral, impartial? Hardly. He should have been impeached.

This is not the only instance in which the electoral system has been manipulated in what amounts to a putsch. There was an election in which electronic voting machines were used widely -- and it was suspected that they were tampered with. Many advanced democracies have forsworn EVMs because of questions about their reliability. But in India, the authorities stonewalled every attempt by computer scientists to ensure that the results produced were legitimate. It was demonstrated by the scientists that it is easy to hack into the machines even via cell phone and thereby steal an election.

There was circumstantial evidence of strange things happening in that election. For instance, one bigwig was trailing by 30,000 votes going into the last stage of counting. Lo! There was a miracle, and he won at the last minute.

Fourth, the first-past-the-post system used in India may be inherently unfair, because small numbers of committed partisans (also known as a 'vote-bank') can turn a defeat into a victory. A proportional system, which gives a more representative picture of the electorate's views, may be the answer. Even in the United Kingdom, from where India took the first-past-the-post idea, is beginning to wonder if it is inappropriate. They put it to vote, and the reform proposal was defeated in a recent election. But we will be hearing more about it in future.

Why is all this happening? A good conjecture is that is because of a group of people who have infiltrated the system in what amounts to a Constitutional coup. Let us look at the US for an analogy.

There is an angry, recent, book by two observers of the US political system. Titled It Is Even Worse Than It Looks, it comments on the rot in their polity, and they attribute it squarely to the antics of one of the parties. Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institute and Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute recently appeared on a PBS show (external link), and here's what they said about the offending party:

'... one of our political parties... has become an insurgent outlier.'

'They are ideologically extreme, contemptuous of centuries worth of policy, economics and social, scornful of compromise, (have) no use much for facts, evidence, and science, and really not accepting of the political legitimacy of the other party. That makes a big difference.'

Unfortunately for India, one could argue that one party in the country has the same attitude -- and believe me, there are no prizes for guessing which party that is. That is as good an answer as there is, as to why India's Parliament has not become an instrument for governing the country.

You can read earlier columns by Rajeev Srinivasan here.

© 2025

© 2025