The real battle for NEET abolition can take much more time and energy, observes N Sathiya Moorthy.

The near-unanimous passage of the NEET abolition bill in the Tamil Nadu assembly on Monday, September 13, goes beyond what is often perceived as Dravidian political rhetoric.

As Chief Minister M K Stalin pointed out in the House, it is about fighting the cause of the socio-economic underdogs against 'elitist sections' which (alone) stand to benefit the most from national-level common entrance exams for medical admissions, as ordered by the Supreme Court.

The purpose of the bill and also the popularity of the cause it espouses became clearer when the four-member group of the Bharatiya Janata Party ruling the Centre chose to stage a walkout. They too did not want to be seen as voting against the bill lest it embarrass both the party and individual legislators back in their respective constituencies and the state as a whole.

The new bill derives from two separate bills the previous All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam government got passed in the assembly, each seeking NEET exemption for the state for under-graduate and post-graduate medical admissions, respectively.

With rival Dravidian majors complementing each other in the passage of the bill(s) when in Opposition, they have highlighted the common concerns that political parties and their leaderships in the state cannot overlook or ignore.

In this case, the new DMK government's bill cites extensively from the report of the Justice A K Rajan committee appointed after the party came to power in May.

Through a less-publicised provision in the famed Mandal Commission case (Indra Sawhney vs Union of India & Ors, 1992), a Constitution bench expressed readiness to exempt individual states from the 50 per cent upper limit for all reservations ordered by the Supreme Court.

The state government now seems to have prepared for such a possibility if and when the NEET issue goes back to the apex court, which had ordered the all-India exams in the first place.

In its time, the AIADMK government of former chief minister Edappadi K Palaniswami appointed the Justice A Kulasekaran commission to undertake a caste census, so as to buttress the argument for the Supreme Court to restore the state's 69 per cent reservations, vetoed by the Mandal verdict.

This went beyond the brief of the of the Justice M S Janarthanam Commission a decade earlier, whose caste data derived from available government figures and not independent of it.

It is here that the Centre's intervention becomes a condition precedent of sorts. Unless the President grants his assent for the bill for the new law, only after which it can be challenged before the Supreme Court for its legality and Constitutionality, the matter may have to end there.

Alternatively, of course, the state government or any affected party (say, a student or his/her parent) could move the courts, seeking a writ of mandamus for the Centre to decide on the bill either way.

It is here that a meaningful intervention by the state government, taking off from last year's Supreme Court ruling in a case emanating from Uttar Pradesh, assumes significance.

The AIADMK government led by EPS, now leader of the Opposition in the state assembly, fixed a 7.5 per cent 'internal quota' for NEET-based admissions for plus-two students from government schools.

Then governor Banwarilal Purohit sat on the bill with the result the state government enforced the decision through an executive order, a rare initiative.

Once the political administration thus crossed the Rubicon, the governor yielded and granted his leave for the bill.

In between, Stalin as the leader of the Opposition called on the governor with the precise request, which set a precedent of sorts compared to the confrontational era of his father M Karunanidhi and the AIADMK's M G Ramachandran and J Jayalalithaa.

Willy-nilly, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government may have also strengthened Tamil Nadu's case when it too ordered 27-per cent 'internal reservations' for OBCs and 10 per cent for EWS (economically weaker sections) under NEET.

The Supreme Court is seized of the matter and has issued notice to the Centre on petitions challenging executive order on 'internal reservations' for OBC-EWS students.

If nothing else, Tamil Nadu can seek to implead itself in this case. Alternatively, it can go on to extend the quota for government school pass-outs up to 50 per cent sanctified under the Mandal verdict.

But the state's intention is to go beyond that and seek exemption, as seeking cancellation of the NEET scheme would require at least a majority of states seeking the same -- and still an apex court acceptance of the same.

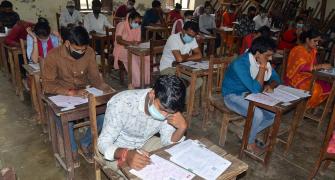

Tamil Nadu has a valid argument when it points to the new elitism introduced by NEET. Though the Justice Rajan committee may not have gone into it in detail, it may be worth the Supreme Court's while, whenever it crosses the bridge, to order a scientific study of NEET pass percentage for students who have undergone 'special tuitions' from corporate or other tutors, who charge fees in lakhs of rupees and which most rural students studying in government schools cannot afford.

First and foremost, such a study could expose the hollowness of the claim that better plus-two syllabi and exam systems alone are the NEET qualifiers.

Instead, even a cursory survey of newspaper advertisements put out by private tutorials, especially on their top ranking students from NEET exams, may give their game away.

While discussing the bill, Chief Minister Stalin highlighted another negative fallout of the elitism attending on NEET. As he pointed out, data has shown that most students passing out of medical colleges in Tamil Nadu, given the higher socio-economic strata they come from, do not join the state medical services, or do not report when there is a rural posting. They either join corporate hospitals or go overseas for higher studies, often settling down there.

By the same token, NEET-pass students from other states should also be following the same route. Translated, the Supreme Court order has facilitated the distilling of Indian medical doctors aspiring for higher studies and career overseas -- thus ensuring better service for patients out there.

It is same as India producing IT professionals for the global market, but with the difference that the exodus of medical brains also drains the nation's future health and health systems.

Given that NEET flows from an apex court verdict, correctives, in this case, have to be taken early on, and has to emanate from the judiciary and not the executive as is often the case otherwise.

Stalin cautioned that soon the state medical services may be deprived of medical doctors owing to this reason. He has a point.

According to a central study, Tamil Nadu enjoyed 1:250 doctor-to-population ratio in 2018. It was the highest in the country and was equal to those prevailing in Scandinavian countries with low populations and high GDP. It is this that is under danger of being consumed by NEET.

Compared to Tamil Nadu's 4 doctors per 1000 population, there are states where the ratio is 1:8000. Tamil Nadu's kind of concerns clearly do not matter to them.

It began with the free school education initiated by the Congress government of K Kamaraj, who also provided free noon meals for children from poor families. MGR institutionalised the meal scheme through annual budgetary allocations.

His successors, Karunanidhi (DMK) and Jayalalithaa (AIADMK) competed to include protein foods like eggs/fruits so as to create a healthy Tamil Nadu, even if not in their times.

With this as the base, the state's achievements on the public health front became possible only with the DMK and AIADMK governments alternating at the helm making a policy decision to open at least one government medical college in every district. As is known, medical colleges come with a teaching hospital, which catered to local needs.

In 2020, for instance, the AIADMK's EPS flagged off work on 10 medical colleges in the 10 new districts his government had created. The party's alliance with the BJP-ruled Centre helped in fast-tracking permission from the Medical Council of India, now renamed as the National Medical Commission -- and both knew the purpose of the TN initiative, which stuck to a Dravidian policy pattern and also went beyond the politico-electoral strategy of the EPS leadership.

In more recent years, successive state governments have also taken extreme care of pregnant women and new-born kids, all of which have helped bring down post-partem and neo-natal death rates when compared to the national average. These include providing health food, vitamins and minerals and also other medicines for both from the day the mother-to-be first reports to a government hospital.

The hospital also keeps track of her periodic medical check-up, alerts her by SMS in advance, and also quizzes her on the why of it if she did not report.

This apart, the government also pays Rs 12,000 for every girl child, to be available for her high school studies. These are all unparalleled measures in the country.

It is this kind of follow-up and medical care that may be lost to the state if there are not enough doctors on its rolls.

It is also for this reason that the state government earmarked PG medical seats for doctors on its rolls, so as to create a super-speciality healthcare system -- and it has been working fine.

Only a fortnight ago, the government ordered the health authorities to proceed against 100-plus PG doctors who had violated their bond conditions in this regard and recover Rs 50 lakhs (Rs 5 million) each from them.

If all these are procedural in character, especially if one left out the people-centric policy-orientation, Stalin has since declared the state government's intention to seek the restoration of education to the state list under the Constitution, as it was at inception.

During the Emergency years, then prime minister Indira Gandhi shifted it to the concurrent list, thereby giving the Centre an edge in matters pertaining to education, including medical education.

Of course, this does not directly involve NEET, which for all practical purpose is a creation of the higher judiciary, rather the highest judicial body in the country.

With that also arises an ancillary question, whose import could well be greater than of the main query: How far and how long can the judiciary impinge on the rights and responsibilities of the executive, as earmarked by the Constitution or enjoyed otherwise?

While highlighting this part, Stalin did not explain how he intended to go about it other than pressing the case for NEET abolition in the state assembly, Parliament and courts.

Generating a consensus among non-BJP ruled states, especially on bringing back education to the state list along with other federal principles that have been lost over the past years, if not decades, may be the starting point.

Yet, it could only be that much. The real battle for NEET abolition can take much more time and energy.

With at least two students -- Dhanush and Kanimozhi -- committing suicide in the state this NEET season, adding to the list that has Anita at the top from 2017, it could be saying a lot, and in more ways than one. More so, when Tamil social media is mourning the avoidable deaths against the 'leakage' of NEET question papers for a price elsewhere in the country.

N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist, political analyst and author, is Distinguished Fellow and Head-Chennai Initiative, Observer Research Foundation.