What should be made out of the Madras high court order involving non-Hindus' entry into Hindu temples, when many non-Hindus are among the hundreds of thousands that have been worshipping at these temples for generations, asks N Sathiya Moorthy.

A recent judgment by the Madurai bench of the Madras high court may have unintentionally opened a Pandora's Box on the unending debate: 'Who is a Hindu?'

The question has triggered a social media debate, often one-sided with minimal participation from the other, conservative interpreters, after Justice S Srimathy ruled that non-Hindus can enter the Sri Dandayuthapani temple in hill-town Palani, dedicated to Lord Muruga, only after giving a written declaration to the temple officials that he/she believed in Hinduism and/or believed in a deity housed in one of the many inner shrines on the temple premises.

The court said that non-Hindus cannot be allowed beyond the kodi maram, or flag-post, where the temple's flag remains hoisted through the annual 10-day festival, without such declaration.

In holding so, the court explained the rationale thus: 'While admiring the architectural monuments, the people cannot use the premises as a picnic spot or tourist spot and the temple's premises ought to be maintained with reverence and as per agamas (or, traditional knowledge).'

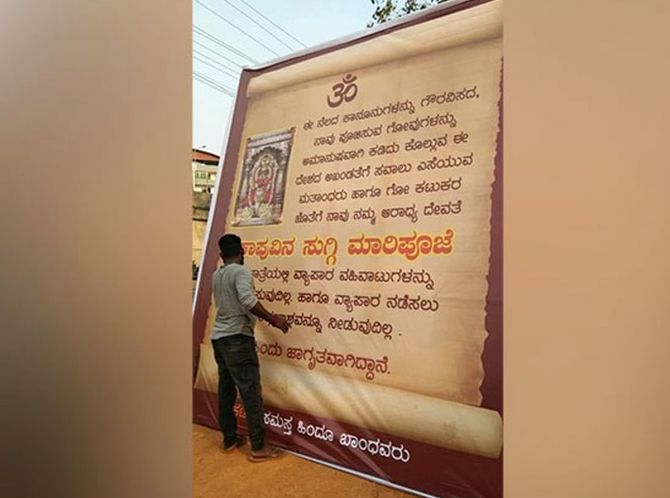

The high court directed the Palani temple authorities to put out notice boards and banners, declaring that non-Hindus cannot go beyond the flag-post, which in most temples is located mostly at the entrance of the temple but mainly inside the outer walls.

The judge observed that though the case pertains only to the Palani temple, the authorities could extend the operational portion of the verdict to cover all temples administered by the state government's Hindu religious and charitable endowments (HR&CE) department. And the court clarified that the 'rights are guaranteed to all religions and there cannot be any bias in applying such rights'.

The Palani case flowed from a petition for direction to the temple authorities to re-install the notice board on non-Hindus being barred from going beyond the flag-post, which is there in most traditional Hindu temples in Tamil Nadu and Kerala in particular and the rest of south India, otherwise.

Traditionally, again, it was an announcement for the local residents not to leave the village/town during the festival days but stay back and help in whatever ways as ordained by tradition to make it a success.

Leaving the religiosity and practical purposes ascribed to the kodi maram, courts and the temple administration have found it convenient to fix it as the entry point of temples to prescribe the limits of entry to non-Hindus.

Across Tamil Nadu, the HR&CE department used to put up such notice boards in all temples under its administrations and all those temples that had a kodi maram.

More than for political and ideological reasons often attributed to the Dravidian rulers, especially the incumbent DMK, the boards were removed during temple renovation but were not always put back -- for no compelling reason, either way.

It was also because of this that the high court has now reminded the authorities what needs doing, though those concerned, including local tour operators and guides, know of the Lakshman Rekha that should not be crossed.

Yet, the high court order has triggered an avoidable debate, rather a wholly one-sided debate in Tamil Nadu, or the majority 'Dravidian' aspect of Tamil Nadu.

Without much contestation, social media posts have questioned the rationale behind the verdict without sounding offensive.

Those that put out these posts seem aware of the contempt-of-court laws as much as the ideological angle(s) that they espouse and seek to expose.

Thus, questions have been raised about the bar on non-Hindus entering Hindu temples, going as far as to argue that it could well be a dampener for re-conversion to the 'parent religion' through association and identification.

In this, there is an unmistakable reference, however veiled, to the Hindutva agenda of the ruling BJP at the Centre, and their cadres' hammering down the opening of Hindu temples in Islamic UAE and Hindu celebrations like Deepavali in the White House and 10 Downing Street, long before Indian-origin Rishi Sunak became British prime minister.

The critics refuse to acknowledge the fine difference between the two -- one, non-Hindus celebrating Hinduism elsewhere, and they wanting admittance into Hindu places of worship without wanting admittance into the Hindu fold, per se. This is a topic in itself with multiple layers.

As if addressing this dilemma, a Dalit scholar claimed in his social media post how non-Hindus cannot convert to Hinduism without caste identification, which invariably they may not possess. Or, at least that is the argument.

Turned on its head, the argument is that you are born into a caste in India if you are not a non-Hindu, and not into the religion.

It raises the larger question. The answer for that question was given by a Supreme Court bench headed by Chief Justice J S Verma, coincidentally, in the years following L K Advani's controversial 'Ayodhya rath yatra' and the attendant 'Mandir-Mandal row' of the early nineties.

Self-styled defenders of the Hindu faith quote only a part of the verdict that 'Hinduism is a way of life'.

The court has since reiterated the observation any number of times in different cases involving different petitioners and respondents, and in different contexts.

They conveniently misrepresent the verdict portion that points out that Hinduism 'does not have any one prophet' or source, and do not cite another part of the judgment that holds how it was wrong to hold that 'Hindutva or Hinduism per se depicts an attitude hostile' to other religions.

'Misuse of these expressions to promote communalism cannot alter the true meaning of these terms,' the court observed further.

In this era of ours, post-demolition, post-consecration just in a single temple town called Ayodhya, the Supreme Court verdict of 1996 applies as much to Hindu zealots that are intolerant and violent as much as to their counterparts in other religions, especially Muslims and Christians in this country.

For, the court had also observed thus: 'The mischief resulting from the misuse of these terms has to be checked and not its permissible use.'

On the Madurai bench's reference to 'architectural monuments', which many ancient Hindu temples across the country, more so in Tamil Nadu from the Chola, Pandya and Pallava eras anyway are and the judge's observation that they are not 'picnic spots', the social media argument raises the issue of archaeological and historic studies and also the possibilities of such archaeologists and historians not being Hindus at birth.

The question is this: 'Should these experts too be barred from entering the temples, which are a store-house of evidence not only to the region's religious history but also of cultural and archaeological history? Or, should they too give a declaration, if so of what kind? They are not there for worshipping any deity, including the presiding deity, and their work may or may not require them to enter the sanctum sanctorum?'

The example of sculptures and stone inscriptions in various parts of the Big Temple in Thanjavur, built by Rajaraja Chola (947-1014 CE), is mentioned as an example. 'After all, the Archaeological Survey of India has fixed a 100 year lineage to declare anything to be of archaeological value capable of being studied by students of archaeology, culture and history.'

Maybe, the court, it is said, should clarify such finer points. The current scheme of obtaining prior ASI permissions for the purpose and denying non-Hindus of the type entry into the sanctum should continue, but the court verdict may have raised a new issue, it is said.

On the other side, it is argued how the Guruvayoor Devaswom Board in neighbouring Kerala had denied entry even to then President Zail Singh when he declined to give a declaration of the kind now prescribed by the Madras high court.

As coincidence would have it, the board cited a decision dating back to 1952, when north Kerala, including Guruvayoor, generally called Malabar, was a part of the composite Madras state.

Questions remained unanswered on the propriety and Constitutionality of the temple board denying permission for the head of State in whose name and stamp even the temple administration falls.

Though parallels were drawn to the past when Tamil kings a millennia back used to change religion from Saivism/Hinduism to Jainism and back and if they visited the places of worship in their own earlier avatar and what was the norm at the time.

Likewise, the Guruvayoor temple has continually denied permission for popular Carnatic music singer and even more popular multi-lingual film singer K J Yesudas, permission to worship inside the temple.

It is another matter that the Supreme Court had long ago given permission for the very same temple board to invite him to perform at a Carnatic music concert during the annual festivities.

Yesudas otherwise does the annual pilgrimage to the Sabarimala Ayyappan temple in southern Kerala, where no such restrictions have been imposed.

As the crowds in the temple have been growing from year to year, from a few hundreds to a few thousands and now to a few millions, in the four-month annual pilgrim season, anyway, it would have been difficult for the authorities to ensure that entry-restrictions are not violated.

In a way, it applies to the traditional bar on the entry of women in the menstrual age-group -- which, of course, is not breached mainly because the local population are wedded to those traditions, whatever be their political or ideological beliefs and electoral commitments.

It was thus that a ruling Marxist minister for temple administration ruled in 2017 that Yesudas could worship at the famous Padmanabhaswamy temple in Thiruvananthapuram on two concluding days of the annual Navaratri festival, coinciding with Dussehra in states other than Kerala and Tamil Nadu, if he gave an undertaking similar to the one in Guruvayoor.

The singer, caught in enough of an avoidable public controversy, stayed away.

There are also other temples in the state that are strict about the practice, and have applied the same yardstick to Yesudas, but there are many others that have changed with the times.

Changing with the times is what social media activists in Tamil Nadu are demanding now after the high court order.

There is a simultaneous fear that after the high court order, certain sections would seek to expand the scope and application of the same to restrict the entry of particular castes to particular sections of the temple.

Suki Sivam, a knowledgeable religious discourser, in a YouTube video, has hinted at the possibility, in stages.

Over the past several years, he has been caught in verbal controversies over his comments and observations involving the 'Brahmin/Aryan divide' of the Dravidian ideological school.

This is the difference from 'Periyar' E V Ramasamy Naicker's days, when opposing 'Brahmin dominance' and opposing the Hindu faith and gods was one and the same. Not anymore.

On the high court verdict this time, Suki Sivam has made a veiled reference to the continuing contest in the matter between the HR&CE department and the numerically small 'Podu Dikshitar' sub-sect of the Brahmin community that owns and controls the temple, by a Supreme Court order obtained at the behest of BJP veteran Subramanian Swamy some years back.

The current issue is about the Podu Dikshitars not allowing others to worship from the 'Kanaka Sabai' at the famous Nataraja temple.

Folklore talks of Dalit farm labour Nandanar, for whom Lord Shiva asked his mount Nandi the sacred bull, to make way for worshipping from outside the temple.

Nandanar is one of the 63 Nayanars or venerated Saivite saints, but there are those who argue that by asking Nandi to make way for Nandan, and not changing the Dikshitars' heart to allow him entry, the Lord too has only sanctified caste segregation.

It is an invalid argument in this era of temple entry, for which Gandhiji and 'Periyar' had fought separately but around the same time.

The question is also raised as to extending the 'temple entry' clause to all religions.

S Anwar, a social historian focussing on religious harmony from the distant past to the recent present, continuously argues that the high court order may go against the spirit of co-existence that has been in place in the Tamil community from time immemorial.

That is because unlike in the North, Islam and Christianity, centuries earlier, came to south India, not through sword and guns, but through trade and people-to-people interactions.

Kings in the south did not have to fight any predator at least initially, though there are occasions, such episodes involving the likes of Malik Kafur and the Portuguese in present-day Tamil Nadu, and Vasco da Gama in Kerala.

Of course, no controversy ends without recent references to the claims that Saivism and Hinduism are not one and the same.

There is a sub-text, of how over a millennium ago, Saivites and Vaishnavites, respectively the followers of Lord Siva and Lord Vishnu, had fought pitched battles, thankfully verbally, over the supremacy of one over the other.

The controversy extends to how the two sects separately fought similar battles with Jains and Buddhists, who had dominated the state's social landscape in the early centuries of the first millennia and before -- and not always stopping with words.

It is often claimed that the near extinction of these two religions, even though of Indian origin, owed to physical annihilation of their practitioners, followers and fellow travellers, though no records of any kind really exist.

These are all thankfully in the past. But to the present-day, there are the annual quarrels between the Then Kalai and Vada Kalai sub-sects of the slightly larger Iyengar Brahmin sub-sect of the larger Brahmin community, fighting over their 'traditional rights' in the conduct of multiple festivals at the Sri Varadaraja temple in Kanchipuram.

They are all followers of Lord Vishnu, but their quarrels over whose naamam, or religious mark, should decorate the forehead of the temple elephant is legendary.

Earlier this year, again, the two sides ended up in fisticuffs on more than one occasion.

In the British era, it had gone all the way to the Privy Council in London. Post-Independence, it has stopped with the Supreme Court in New Delhi and the Madras high court, closer home. The case is still pending before the high court.

In this overall background, what should be made out of the high court order involving non-Hindus' entry into Hindu temples, or the need for their giving a declaration of the kind specified, especially when such instructions cannot be enforced in festive seasons, where many non-Hindus are among the hundreds of thousands that have been worshipping at these temples for generations?

N Sathiya Moorthy, veteran journalist and author, is a Chennai-based policy analyst and political commentator.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025