'... That they should emerge as role-models to be emulated by the fellow countrymen; and that the middle classes should not stick only to hate-filled and scornful criticism and condemnation against the state of affairs,' remembers Mohammad Sajjad.

In our academic and popular domains, discussions about the Muslim component of India's evolving nationhood in the late 19th and early 20th century, suffers from serious misconceptions.

Owing to such misconceptions, majoritarian accusations against the Muslims in the making of the Indian nation attempt at acquiring certain degree of credence.

This still continues to have serious implications in our lives.

Through interventions in academic as well as popular domains such misconceptions, therefore, need to be rectified.

Religious particularism was the phenomenon unmistakably associated with all the reformers of the 19th century.

But only the Muslim reformers, writers and public intellectuals are seen with a different prism and with an accusative tone of 'impediment' in the way of the evolving united or composite nationalism.

Sir Syed, his companions and their Aligarh Movement are identified more as something which eventually engendered separatism.

Elements of universalism, rationalism, pluralism, and their writings exposing colonial plunder and agrarian devastation remain grossly unattended or downplayed. [In this context, ironically, even the founder of the Banaras Hindu University, Madan Mohan Malaviya (1868-1946) too is looked upon more in the discussions on identity-politics. His engagement with the economic affairs in late 1930s, and the factors behind his marginalisation from the Hindu Mahasabha, in the last decade of his life, remains unexplored].

Sir Syed's expositions on agrarian devastations and his efforts towards rehabilitating agriculture to enhance production with modern techniques and tools remain under-studied, even though his tract (1858) on the causes of the uprising of 1857 spelt it out quite forthrightly, and ever since then he kept writing extensively on the subject.

Thankfully, two Urdu monographs dealing with his agrarian thoughts and works and on his articulations against racism of the colonial administrators have been published in recent years by Professor Iftakhar Alam Khan.

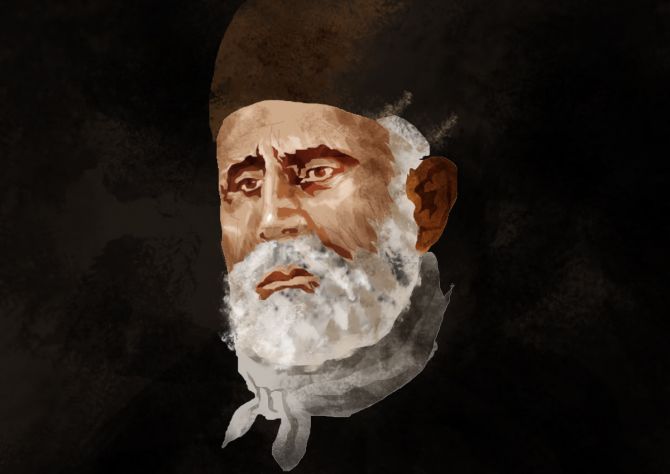

This column, however, concerns itself with one of the leading writers and a very close companion of Sir Syed -- Khwaja Altaf Husain Hali (1837-1914) of Panipat.

His contributions in modernising the literary criticism (Muqaddama-e-Sher-o-Shayeri), biographical writings (biographies of Sadi, Ghalib, Sir Syed, etc), and his reformistic long poems (musaddas) are too well known not only to the Urdu language readers but also beyond them.

Hali's other writings on the themes such as his expositions against the colonial plunder, caste and gender-based discriminations and colonial oppression of the peasantry, his expectations from the emerging middle classes, remain less popularised among the Urdu literary circles, and almost completely missing from the studies in history and social sciences.

What comes out here in the following lines that Hali was not a mere subscriber of Sir Syed's views.

Scholars of nationalism such as Partha Chatterjee, identified three phases of nationalism in colonial India.

He called the first phase as 'Moment of Departure', and argued that in the spiritual and cultural domain the discourse of nationalism was not as much derived from the West.

He cited the example of the Bengali language writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894), as to how his oeuvres and articulations eventually provided with a cultural self-confidence to the Indian literati which soon paved way for anti-colonial mobilisation and solidarity, at the turn of the 20th century.

In this perspective, the Urdu writings of Muslim intellectuals, for long, remained neglected by the historians.

A welcome intervention was Mushirul Hasan's book (2005), Moral Reckoning: Muslim Intellectuals in 19th Century Delhi.

A specific focus on Hali would therefore help correcting certain misconceptions about the characterisation of the Aligarh Movement.

I came across a wonderfully well-researched slim Urdu monograph, Hali Ka Siyasi Sha'oor (Hali's Political Consciousness).

This is a PhD thesis of a famous Urdu poet, Moin Ahsan Jazbi (1912-2005) (published in the 1950s).

Substantially deriving from that, I think, it is worthwhile to share the useful findings of this research in the public domain for consumption beyond the Urdu reading public.

This would be helpful in shedding and rectifying certain misconceptions about the Muslims and the evolving Indian nationalism.

Born in a not so affluent (lower middle class) zamindar family of Panipat, Hali's initial awareness about the colonial oppression is attributed to his coming in touch with Mustafa Khan Shaifta (1809-1869) of Delhi.

Unlike Ghalib, Shaifta disliked exaggerations in literary articulations and preferred direct and candid prose in narrating events and processes.

Half of Shaifta's jagirs/landholdings were confiscated by the British Raj in the wake of the upsurge of 1857.

He was incarcerated by the Raj.

Nawab Siddiq Hasan Khan (1832-1890) of Bhopal rescued him from there.

Owing to this, Shaifta harboured deep anguish against the Raj.

Hali may have received these anti-British feelings from Shaifta as he came into Shaifta's touch for scholarly learning in Delhi.

Hali met Sir Syed at Shaifta's place in 1868.

After Shaifta passed away, Hali lost his job at Jahangirabad, and he shifted to Lahore in 1872.

He stayed there almost for next four years serving for the Punjab Government Book Depot there.

He came in touch with the Urdu renderings of English language works.

In Lahore (1874), Mohammad Husain Azad (1830-1910) launched a new kind of poets' assemblies (mushaira), asking the poets to compose poems to inculcate natural, scientific temperament and rationalism and on Indian cultural and geographical imageries.

Hali composed four important long poems in these mushairas.

The first one was his long poem, Nishat-e-Ummeed (the Delight of Hope; around the same time, Sir Syed also wrote an allegorical prose, Ummeed Ki Khushi).

In fact, intellectuals like Hali were just struggling to look for hope amidst the despair that came with colonisation.

Hali's next two long poems, Hubb-e-Watan (Love for homeland or patriotism) and Munazera-e-Rahm-o-Insaf (Dialogue between Mercy and Justice), went a step ahead; the two human qualities are personified to dramatise the debate.

Also, these poems were not meant to address Muslims only.

It was more universal in terms of target-audience.

In these poems, having hinted at the post-1857 retributive massacres, Hali, though in a cautious and guarded manner, underlines the ravages such as famines, hunger, poverty, morbidity, lack of education and all such deprivations which have come up as a result of colonial exploitation.

To get rid of all these evils, he pins his hopes on the affluent, educated, accomplished segments of fellow Indians.

He attributes these problems to the miserliness and self-centrism of these classes of Indians.

He also speaks out against caste-based oppression and hierarchy, and condemns the Syeds and Brahmans for subjugating the Shudras.

Shedding such hierarchies for the sake of bringing out socio-economic equity is what Hali calls Hubb-e-Watan (love for homeland or patriotism) and Qaumi Khidmat (service to the nation).

Also to be noted, Hali did not use the word, 'Qaum', here for a specific religious community.

He uses it essentially for all Indians.

In these poems composed for public mushairas of Lahore, Hali extols rationalism and makes distinctions between older (pre-colonial) and newer (colonial) forms of governance.

He disdains authoritarian, personalised form of governance in the pre-colonial era and welcomes certain theoretical features of colonial governance such as rule of law, freedom of press, legislative council representations. [Interestingly, in one of his long essays he expounds on journalistic ethics].

Later, he would also underline the disjunctions between the theory and practice of such 'regenerative' features of colonial governance.

Compared to Sir Syed, Hali is less ambiguous in articulating such critiques.

This is understandable, given the fact that Hali was twenty years younger than Sir Syed, and Hali lived to write for 16 years after Sir Syed's death.

Hali would also remain sceptical about the claims of equality before law made in the Queen's Proclamation of 1858. [Though, a fresh look into the writings of the last seven years of Sir Syed's life, do reveal that contrary to prevailing perceptions, Sir Syed too was quite vocal in subjecting the colonial plunder and racism to unambiguous criticism.]!

Couldn't we therefore say, just as the critics of the current Modi regime look at the disjunctions between the proclamation of sab ka sath, sab ka vikas, sab ka vishwaas, and the practice of exclusion, discrimination and oppression such as through the disabling citizenship laws and inaction against and patronage to the cow vigilantes?

There are some innocent or self-centric people who look upon such deceptive slogans with hope and trust.

Hali offers an eye-opener poem with these lines: Dard aur dard ki hai sab ke dawa ek hi shakhs/Yaan hai jallad o maseeha ba Khuda ek hi shakhs/Qaafiley guzrey wahan kyon kar salamat waaiz/ho jahan raahzan aur raahnima ek hi shakhs. [The one who inflicts the wound, claims to offer ointment to the wound/Where both the oppressor and the saviour are one and same person/how can the caravan will be safe there o defenders of the regime/which is both the leader and the plunderer of the caravan]

Thus, Hali's essay (1871) on assessing Sir Syed's efforts, his anti-colonial, patriotic poems at Lahore (1872-1875), his musaddas, Ebb and Tide of Islam (Madd-o-Jazr-e-Islam), his scientific mode of historical enquiry, remained intact with the sole concern of persuading the colonised society to go for self-introspection, and to move on to gain a cultural pride and self-confidence.

For the magazine of the MAO College Aligarh, he wrote an essay in July 1895, reflecting upon the questions such as why and how have the Indian Muslims been incapacitated to act for their emancipation? Why have they stagnated to form a progressive, educated, professionally trained middle classes among their ranks? He then analyses the debilitating impact of the Asian forms of autocratic governance with personality cult.

His arguments (through the relevant poems and essays) specifically need to be re-read in the present context.

Such a re-reading, keeping in mind the Muslim location in the current majoritarian regime, may help grasping Hali's arguments with relatively greater clarity.

He makes a distinction between two kinds of subjugated people.

One is the group which psychologically identifies itself with the ruling classes, and the other segment feels excluded from the governing classes: authoritarian regimes tend to incapacitate the subjugated and excluded people who eventually begin to feel helpless.

They just lose interest in the affairs of governance and statecraft.

They begin to intellectually and psychologically stagnate and degenerate.

The elites within the former category will feel contented with the State's doles and favours and employment; they would debilitate their self-respect and their larger concerns of socio-religious and economic reforms; they would, thus, lose their self-confidence and would eventually exhaust their potential and concern for uplifting the deprived segments of the fellow countrymen.

This, according to Hali, is even truer for the former category of the population.

Whereas, the latter category, by virtue of exclusion, tend to develop a spirit of self-help and would not like to depend as much upon government services as upon developing their own craft, skill, trade, agrarian production, and other independent professions.

Essentially speaking, Hali seems to put the post-Mughal Muslim elites in the former category.

Hali would further argue that such people tend to become more superstitious and fatalist (taqdeer ka parastaar aur tadbeer se kinarakashi).

This is what he diagnoses in his poem, Shikwa-e-Hind (India's complaints), besides the essays.

Hali's diagnosis and exposition of moral degeneration of India's Muslim elites is more frank in his essay, 'Tijarat Ka Asar Aql-o-Akhlaq Par' (impact of trading profession upon wisdom and morality).

In this, he argues that the Muslim elites depended more upon government jobs and least upon trade; that trade is a profession which requires modesty, sweet and polite talks, and adventurous spirit, to take risks.

Hali tends to suggest that without economic uplift, no community can really sustain the project of social reforms.

His poem, Ta'assub wa Insaf strongly disapproves ta'assub (prejudices) which according to him is enemy of both individual and society; that insaf (justice) is the antidote for ta'assub.

This, he says, requires rationalism as its necessary prerequisite, and that without this, nobody can really attain insaniyat (humanitarianism) and wasi'-un-nazri (broad mindedness).

He insisted on these aspects in his address to the Educational Conference as well.

He argued that the Arya Samaj was able to sustain and expand its reformist projects because of the support of the trading communities.

Jazbi (page 86) pleads that one should appreciate the deep political insights of Hali pertaining to what Karl Marx also said, degenerative and regenerative aspects (taareek aur raushan pehlu) of British colonialism in India.

While Sir Syed would mostly point out the regenerative aspects, Hali, on the other hand, would be more inclined to expose and critique the degenerative aspects of colonial rule.

In his essays, besides his didactic poems, Hali would expose how industrially advanced metropolitan countries have subjugated the Asian and African countries to exploit their natural resources, and they would first plunder and resort to massacre shattering the administration, peace and justice.

This is the colonial political economy, he says, and asserts that the doctrine of free trade is in the interest of England, and that such a policy cannot ever dispense justice to the colonised people.

His prose writings not only in the form of essays but also as prefatory notes to his poems go on elaborating upon his thoughts on colonial ravages in economy, culture, education and whatnot.

His poems, Tuhfat-ul-Ikhwan (Gift to Brothers, 1902), and Dehli Ka Jalsa-e-Conference are illustrative examples to this effect.

On the gender issue too, Hali critiqued the purdah sytem.

His poems, Munajat-e-Bewah (Widow's Supplications), and Chup Ki Daad (Voices of Silence, 1905) are better known for exposing the kind of subjugations that aristocratic Muslim women suffered at the hands of their men.

Though his advocacy for modern education to women was stronger as compared to his concern for purdah.

In fact, at times, like many other reformists of colonial era, he also appears to be contradicting himself on this issue.

Jazbi accuses him to have not been brave enough on this count.

His cautious moves in this respect are obliquely meant for Sir Syed as well, more particularly in his poem, Reform Ki Had (Limits of Reforms).

While Sir Syed had reservations about modern education to women, Hali had established a girls' school in Panipat in 1894.

In terms of modern education, compared to Sir Syed, Hali puts greater emphasis on technical education (1876).

Here too, Jazbi's assessment needs to be re-evaluated.

There are adequate writings of Sir Syed, though, in late years of his life, insisting on specialised education for running internal and international trades as well as industrial training and research.

Hali had clear vision about the objectives of a university, which, he said, should not be a degree-mill producing clerks (karkhana-e-clerk saazi) obedient to the State; rather, these should primarily produce the thinking people.

In his interrogative essay, Hum Jeetey Hain Ya Mar Gaye? (Are we dead or alive?), he insists on acquiring skill and education for self-help and for independent professions (azad pesha), including trade and agriculture.

Hali did not have much expectation from the affluent segments and from the religious scholars.

While the former, according to Hali, were self-centric and immoral consumerists, the latter were just inward-looking.

He asks the middle classes not only to become talkers, but also the doers and that they should emerge as role-models to be emulated by the fellow countrymen; and that the middle classes including the pen-pushers should not stick only to hate-filled and scornful criticism and condemnation against the state of affairs.

In his poem, Qaum Ka Mutawassat Tabqa (1891) and long introductory essay to that poem, he persuades to work towards creation and expansion of middle class and he pins greater hopes on this class to take care of the poor and illiterate downtrodden segments.

In a letter (1904) to Abdul Halim Sharar, Hali was concerned about growing Hindu-Muslim tension and colonial roles in exacerbating these, yet, he expressed strong hopes that with meaningful rational education, the two communities will work out how to live in amity and peace. (The colonial role in pitting the Muslims andHindus against each other is articulated best in his poem, Tadbeer-e-Qayam-e-Sultanat).

His arguments in this letter would subsequently resonate in W C Smith's book (1946), Modern Islam in India: A Social Analysis and Jawaharlal Nehru's book (1946), Discovery of India, wherein, the two authors talk about the 'lag theory' (late formation -- almost by half a century-- of educated modern middle class among Muslims; precisely this is the time-gap between foundation of the Brahmo Samaj and the MAO College, Aligarh) as the reason for the rise of communal conflicts.

Along these lines, Hali had already written an essay (1880), Kya Musalman Taraqqi Kar Saktey Hain.

Reiterating these, Hali wrote another essay in July 1895 and his presidential address at Karachi in 1907, further reiterated, persuading Muslims to works towards formation of modern educated middle class and to develop capacity-building more through independent professions, and less through government services.

To this effect, his poems, Ba Nang-e-Khidmat (1887) and Falsafa-e-Taraqqi are of particular importance.

Hali was therefore a strong advocate of the economic boycott of the Swadeshi Movement against the Partition of Bengal along communal lines in 1905.

He wrote a long essay endorsing the agitation.

He insisted on shaking the financial foundations of the Raj, which, he believed, will pave way for equality of economic opportunities for all the India.

In short, moral of the foregoing biographic story is: Identity-based fractious politics can be trumped only with economic nationalism.

The foregoing assessment of Hali would therefore suggest that the difficult times we are living now, a revisit to these public intellectuals of yesteryears would perhaps be instructive.

This significant study of Altaf Husain Hali by Jazbi and the full text of the essays cited therein should therefore be rendered into English, Hindi and other Indian languages.

Such exercises may pave ways for erecting people's solidarities for a better, equitable, prosperous India.

Mohammad Sajjad teaches Modern and Contemporary History at Aligarh Muslim University and is the author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge 2014/2018 reprint).

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com