'Coronavirus has occasioned us to see how copious Modi's mojo bag is,' says Shreekant Sambrani.

"Aa Modi aapanne bahar nahi avawa de (Modi will not let us step out)," Haribhai, a tomato vendor, told me when I last visited our semi-wholesale market.

That same evening Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi urged us to observe Janata Curfew two days later, which was a prelude to the nation-wide lockdown another couple of days hence.

Obviously, Haribhai's insight into his prime minister matches that of Modi's into his otherwise undisciplined and virtually ungovernable country, enabling him to persuade its vast majority to willingly lock itself in for a protracted period.

When he pulled off the great Indian currency vanishing trick in November 2016 to the great appreciation of precisely those who suffered most from it, we were stunned.

Within months, he and his party won the prize state of Uttar Pradesh with a thumping majority and two years down the line, an unprecedented majority for a second term in the Lok Sabha.

Surely that cannot be topped, we thought, but coronavirus has occasioned us to see how copious Modi's mojo bag is.

Social scientists and historians will spend many years studying these amazing feats of a leader persuading people to bear severe pain on his sheer say-so.

Here is a layman's attempt to fathom this phenomenon based on some purely anecdotal evidence.

Just a few days ago, a lawyer-friend told me of his first meeting with Modi. My friend had gone to Delhi in the late 1990s to meet a Gujarati financier in connection with a case, where he was introduced to the future prime minister.

Modi was exiled to the capital by the Bharatiya Janata Party's Gujarat leadership.

My friend talked of Modi's narration of a childhood incident, which he termed a defining moment in his life.

A sadhu used to visit the Modi household for alms of grain or flour. One day he asked for a meal.

He then predicted the future of the three boys who shared the meal with him: One would become a government official (he did), another, a trader (he did) and the youngest, Narendra, had chakravarti yoga (an emperor's future).

My friend narrated several more details that lend credibility to his account but space constraints prevent their mention here.

That singular occurrence could possibly explain many events in Modi's passage through the next half a century or so.

His belief in his manifest destiny would steer him away from normal family life, as that would tie him down to the mundane details of everyday survival.

He would pore over glories of ancient empires, a first step towards a belief in Hindu renaissance

That would lead to his membership of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and its political organ, the BJP.

His decision to reject offers of minor offices such as a municipal corporator in Ahmedabad or as a member of the Gujarat legislative assembly in the 1980s and 1990s fit in with his pursuit of the ultimate goal, lest these wayside stops divert his focus from his true destination.

In Delhi, he hitched his wagon first to his contemporary and steadfast defender Arun Jaitley and later to the BJP paterfamilias Lal Kishenchand Advani, all part of his apprenticeship to know the ins and outs of the power Chakravyuh. The rest, as they say, is history.

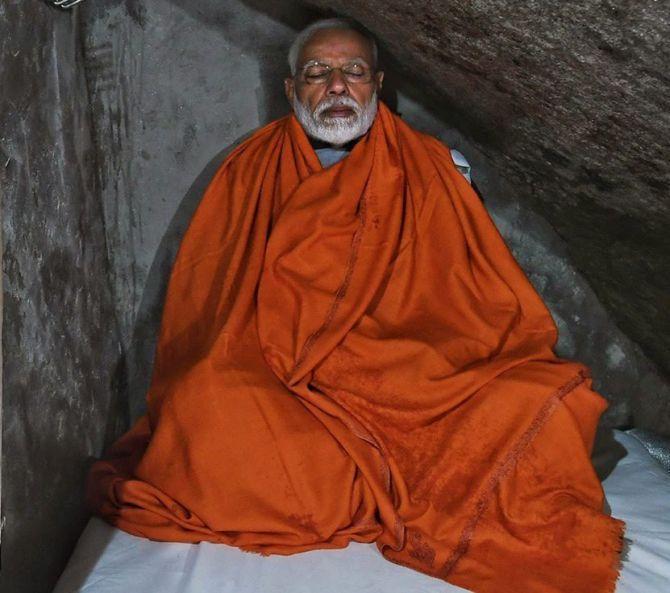

The other major impact this event had on Modi is his lasting fascination with the mendicant's ways.

He sojourned in the Himalayas for long.

He shunned salaries till he became the Gujarat chief minister in 2001.

He managed until then on shared living of the swayamsevaks and token pocket money for bare minimum necessities from patrons such as the Delhi financier and a Vapi-based Muslim industrialist.

Even in office, he seems to have espoused a relatively spartan life-style, except for his penchant for designer glasses and pens, and on one short-lived occasion, a monogrammed designer suit.

There are no vacations or retreats, and the foreign visits are all business with a generous dose of appeal to non-resident Indians, in stark contrast to the predecessors, especially of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, something we are nudged into noticing.

His public appeals are a mix of high moral ground and nationalist fervour, much like that of a sadhu.

Whether it is Swachchh Bharat or Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao, it is the same mix.

Even the purely political rallies resemble evangelical meetings, with dollops of hectoring and sarcasm.

Most of this comes wrapped in the flag./p>

Even as everything is prime-minister-centric, he mostly mentions himself in the third person.

All this is not just familiar, but more importantly, hugely acceptable to the crowds that gather to see and hear him.

Like a practiced fakir, he only asks you to give him something -- your stash of currency or, as on March 24, your three weeks.

That is your moral duty, he says, and steeped as we are in honouring such requests by sundry godmen, we do as he demands of us.

The key is to see Modi as the mendicant-prince, willing us to do his bidding.

But in the present case, as my wife recalled the Bard about Henry IV: 'Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.'

Shreekant Sambrani is an economist.

© 2025

© 2025