'The experience so far is a shocking example of how critical scheme of national importance can be brought into disrepute by inefficient and badly designed implementation,' says Dr Madhav Godbole, the former Union home secretary.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi must be acclaimed for taking the courageous decision to demonetise high denomination notes.

During the last 70 years since Independence, every political party has indulged in the rhetoric of fighting black money, but there has been no concrete action, except for the demonetisation by Morarji Desai's Janata Party government in 1978.

However, since the government fell soon after and there was no follow-up action, its impact was limited.

The National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, in its report, Aspects of Black Money in India, had estimated black income generation at 18% to 21% of the gross domestic product (at factor cost) for the year 1983-1984. There has been steep increase in black income since then.

The direct taxes enquiry committee (1971), popularly known as the Wanchoo Committee, in its interim report, had recommended demonetisation of high value currency notes.

The report was discussed in a series of meetings with the then finance minister Y B Chavan, on whose personal staff I worked at the time, and it was decided that the recommendation should be acted upon.

In view of the importance of the subject it was decided that the finance minister should first discuss the matter with then prime minister Indira Gandhi before further steps were initiated.

When Chavan called on Indira Gandhi and explained what he had in mind, she asked him only one question: 'Chavanji, are no more elections to be fought by the Congress party?'

Chavan got the message and the recommendation was shelved. (Madhav Godbole, Unfinished Innings, 1996, pages 87-88)

Against this background, Modi must be complimented for taking a normally unthinkable step which would change the face of this country.

It is sign of political maturity that common people all over the country have welcomed the move and supported the objectives underlying it.

However, it is evident that they have been put to tremendous hardships and inconvenience.

The print and electronic media is bringing out the enormity of their privations every day. The question therefore needs to be asked whether preparatory actions for demonetisation could have been chalked out more thoroughly, thoughtfully and with a greater foresight. Several lacunae are evident.

The government has stated that the planning for this momentous step had begun 10 months ago. The government thus had enough time to make the scheme as fool-proof and workable as possible.

Unfortunately, this does not seem to have happened and there are too many yawning gaps which have led to tremendous misery and inconvenience all around.

None of the measures below would have compromised the secrecy of the operation in any way. With the nationalisation of banks in 1969 and encouragement of the co-operative sector in development, the spread of banking has been far and wide, including in the rural and semi urban areas.

This factor ought to have been taken into account while devising the scheme of demonetisation.

The decision of the government to exclude co-operative banks from the implementation of the scheme has raised many awkward questions.

The prime cause of this is the dual control on supervision of these banks by the RBI and the state governments. I firmly believe that all banks must be brought under the RBI's sole supervision. Let us hope this issue will be addressed with earnestness at least now.

Non-availability of new notes in sufficient quantities on the day of demonetisation is also shocking and totally inexcusable. Specious reasons are being advanced for delays, including in recalibration of ATMs. Delays in bringing these machines into operation could have been easily foreseen and taken into account.

Since large areas in the country are still without ATM facilities, orders could have been placed in advance for new ATMs taking into account the configuration of the new notes of the denomination of 500, 1,000 and 2,000. The old ATMs after their recalibration could have been sent to the areas in which this new facility is yet to be provided.

The perceptions of people in the very sensitive exercise of demonetarisation should also have been given due weightage.

Thus the explanation given by the government for the running of colour from the new 2,000 rupee note, that if the colour runs, it is a genuine note, is ludicrous, to put it mildly.

The requirement of additional staff in banks could also have been anticipated and a scheme put into effect for re-employment of retired employees of the banks for a fixed duration.

For a continent sized country like India time limits provided for conversion of old notes, and payment of bills should have been long enough so as to create a sense of assurance among the people that there is no need to run to the banks and ATMs immediately.

As an exceptional measure, the banks could have been kept open for all 24 hours to cater to the demands of people who have offices and work schedules to attend and can do their banking transactions only after office hours.

This is also true of large numbers of people in the business, informal sector, daily wage-earners and others.

It needs to be reiterated that demonetisation is (hopefully) a once in a life-time phenomenon and the follow-up actions also need to be taken care of as an exceptional measure to ensure smooth changeover to the new system.

The experience so far is a shocking example of how critical scheme of national importance can be brought into disrepute by inefficient and badly designed implementation.

Finally, the war against black money must not end with demonetisation.

The government must announce in no uncertain terms that this is just the beginning and a series of steps would follow to bury the ghost of black money for ever.

Even in this regard the record of performance of successive governments is hardly anything to write home about.

Benami transactions, for example, have continued unabated despite the law on the subject which has remained on paper for years together.

There is rightly a perception among citizens that large loan defaulters and law-breakers have the protection of the political elite and have therefore gone scot-free.

The nexus between criminals, politicians and bureaucrats has been conveniently overlooked by the government. The frightening phenomenon of corruption has never been addressed with any seriousness by any government.

A comprehensive national policy needs to be adopted for eradication of corruption (Madhav Godbole, Good Governance Never on India's Radar, 2014, pages 213-17). The rhetoric 'zero tolerance for corruption' is as empty and meaningless as 'the law will take its own course.'

The unfinished agenda for dealing with black money is formidable. But the wheel does not need to be reinvented.

The question is whether we, as a nation, are prepared to put our shoulders to it to make it move.

Dr Madhav Godbole is a former Union home secretary and secretary, justice.

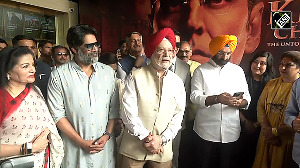

IMAGE: A queue to deposit or exchange high denomination banknotes outside a bank. Photograph: Amit Dave/Reuters

© 2025

© 2025