A wise politician would disarm his critics, try to take them along, co-opt them, or, at least, take the criticism in his stride.

Developing a thick skin ought to be an essential part of any politician's toolkit, notes Virendra Kapoor.

It is hard to believe that even otherwise clever politicians soon after attaining power abandon the founding principle of their profession.

If politics is indeed the art of winning friends and influencing people, why would so many politicians once in power go about systematically alienating large sections of the population, especially when it yields no return either in enhance popularity or improving electability?

Bringing to bear the heavy hand of State power on critics is almost always self-defeating.

For it may temporarily soothe the hurt egos of powerful politicians but it does little to add to their appeal.

If anything, such intolerance gratuitously bestows a halo of victimhood on the critics who would otherwise go largely unnoticed.

In the process, the regime earns a highly avoidable opprobrium.

A wise politician would disarm his critics, try to take them along, co-opt them, or, at least, take the criticism in his stride.

Developing a thick skin ought to be an essential part of any politician's toolkit.

Being impatient with every little display of dissent and non-conformity is always counter-productive.

Dissent gets amplified multiple times if attempts are made to squash it with charges of sedition or other extra-constitutional actions.

Ideally, if criticism is valid, politicians ought to welcome it, and correct themselves; if it is motivated by prejudice, which it often is, it is best to treat it with scant respect and to leave the critic well alone.

Stone-throwers are prone to get frustrated on finding that they have missed the target.

But rulers not only score a self-goal, inviting charges of authoritarianism and intolerance, by seeking to quell dissent.

A critic who finds himself at the receiving end of the heavy-hand of authority feels more than compensated by the sympathy and support a/he elicits from wider sections of an aware and informed citizenry.

Another practical reason why the rulers need to leave critics well alone is that in a country of 1.36 billion people, given the level of literacy and civic-consciousness, only a small, urban-centric elite concerns itself with the outpourings of liberal, English-speaking commentators.

Half the time media columnists find themselves actually addressing their own peers, rather than being able to reach out to the proverbial man in the street.

Since most politicians make it their business to win the hearts and minds of the man in the street, the average Joe, who does not constitutes the targeted consumer of such high-fluting critiques, is unconcerned.

Therefore, it is best to adopt an attitude of live-and-let-live with the habitual naysayers among the urban-centric elites.

It is in the above context that the reported resignations from Ashoka University of public commentator Pratap Bhanu Mehta, and, following it in solidarity with him, by Arvind Subramanian are all the more surprising.

With one stroke, the government has bestowed a halo of victimhood on Mehta, without gaining anything tangible in return.

It has played straight into the hands of the critics who are bound to cite it as yet another brazen example of creeping authoritarianism and an 'elected autocracy.'

Courting bad publicity even in academic circles and in the wider student communities in no way helps the government cause.

Such self-goals cumulatively tarnish the image of the government at home and abroad.

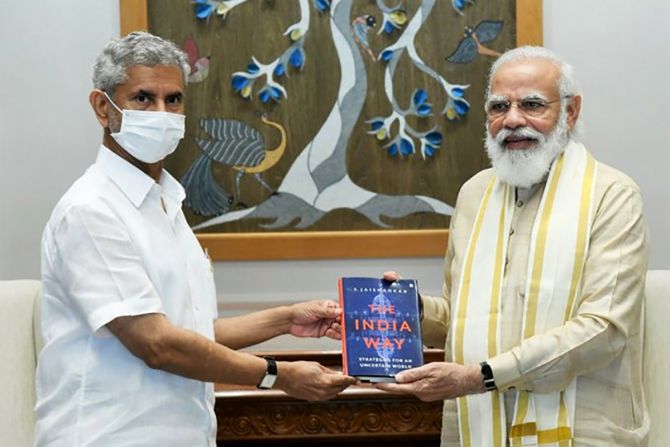

In fact, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar's strident tone in countering criticism from foreign quarters was least helpful.

It made national headlines. Such an uncharacteristically aggressive attitude, calling critics hypocrites and 'self-appointed custodians of the world...' sounds arrogant, nay, churlish.

The career diplomat who has spent a lifetime conveying tough messages but always hidden behind velvet gloves was needlessly pugnacious.

In his new persona as a politician the former foreign secretary seemed to be at pains to present himself as an ultra-nationalist.

Only recently, the manner in which the MEA reacted to the tweets by Greta Thunberg, the teenage Swedish environmental activist, and Rihanna, the Barbadian singer, who had tweeted sympathy for the protesting farmers, was bewildering.

Why get so hot under the collar and elevate what are after all mere tweets by global celebrities with little or no understanding of the ground reality in India, and, thus, impart them undue significance?

Even well-wishers of the Modi government felt bewildered by the official response to the tweets by Greta and Rihanna.

'No comment' as an official response would have been the correct thing to do.

But the way the MEA reacted, it showed its peeve, its vulnerability.

Or is it that Jaishankar at every moment feels obliged to don saffron colours as a new convert to the BJP cause? Aggressive and unapologetic nationalism reflects an isolationist mindset at a time when India has finally shed its reticence and embraced the US and other democratic powers to counter Chinese aggression and belligerence.

Flashing an iron fist at foreign critics, the assorted NGOs, non-profits such as Freedom House and Amnesty International and a host of Western publications is not the answer to accumulate soft power.

Even Western critics who habitually pick on the Modi government due to their prejudiced world view and an ingrained resistance towards a home-grown inward-looking party with its roots in India's ancient culture need to be treated with due courtesy and decorum.

Clouting them on the head serves little purpose.

Of course, no one in the West or, for that matter, anywhere else has a right to interfere in our internal affairs, but in an inter-connected world much significance is attached to a country's standing in the global capitals.

The intangible asset of a vibrant, functioning democracy where civic rights are respected and criticism of government policies and actions not met with stringent punitive measures further eases the way for her to conduct business with the rest of the democratic world.

A shared faith in basic human rights is the common thread that binds all democracies together.

Without doubt, some of the barbs, slings and arrows aimed at the Modi government are motivated by sheer malice and prejudice, stemming from refusal to reconcile to a self-assured prime minister who pointedly ignores the Western media and its domestic feeder, the English-language urban-centric press.

Yet, it sounds peevish for Modi ministers to stoop low to counter its critics in their own language.

Being self-assured and self-confident is good, but turning up one's nose at foreign critics with contempt, especially when India is opening up to foreign investments and technologies, may be counter-productive.

Admittedly, a BJP government invariably attracts sharper criticism from Western quarters in comparison to other governments.

Maybe it is the party's self-avowed belief in aggressive nationalism and rootedness in Indian soil, in contrast to the Westernised culture and mores of the Nehru-Gandhi family, which evokes a sense of antipathy among the New Delhi-based Western media.

Yet, being needlessly aggressive in response does not pay.

Learn to take even ill-informed criticism in your stride.

Punitive actions against critics only go to prove them right.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025