The Election Commission is perhaps the only body in the country still untarnished and commanding universal respect round the world. It has often been savaged by the ruling political dispensations in the past but the Election Commission has come out with flying colours in every case including the latest one against West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, says B S Raghavan, West Bengal's chief secretary in the early 1970s.

India's Election Commission has once again done the country proud by cracking the whip against a chief minister who thought she could get away with defying its directive given in the exercise of its repeatedly affirmed Constitutional powers to ensure the conduct of free and fair elections.

The vitriolic diatribe against the Commission by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee can only be described as outrageous even when set against the abysmal standards of behaviour of the political class.

She didn't stop merely with proclaiming in public her determination to disobey the EC's orders transferring one district magistrate, two additional district magistrates and five district superintendents of police to maintain the sanctity and impartiality in the conduct of the impending election to the Lok Sabha.

She accused the EC of issuing those orders at the behest of the Congress. She went to the extent of declaiming openly that the phasing of elections in the state by the EC was aimed at facilitating rigging with a view to ensuring the victory of Congress candidates.

In the issue of the EC's ultimatum to the state administration to carry out its orders by 10 am on April 9, was also an implicit threat that or else, the EC would be forced to countermand the election in the state and even initiate proceedings to derecognise the Trinamool Congress Party.

Mamatadi saw the light and meekly climbed down. She wasn't the first chief minister to do so, though.

The EC and even individual members of that body, perhaps the only one in the country still remaining untarnished and commanding universal respect round the world, have been savaged by the ruling political dispensations in the past also, but the EC has come out with flying colours in every case.

In 2003, Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Digvijay Singh similarly took a public stand against the EC's order to shift three district collectors.

In 2005, then Haryana chief minister Om Parkash Chautala, taking umbrage at the EC transferring the state's then director general of police M S Malik, (whose wife was the ruling combine's candidate for a Lok Sabha seat) went one better. Declaring that his government would 'neither issue orders for his transfer nor submit any panel (of names for new police chief) to the EC', Chautala called the EC a 'tool of the Congress made of retired bureaucrats rewarded for their loyalty to the party... (They) get EC posts for six years and go all out to help the Congress... After their term in the EC, they eye a Rajya Sabha nomination as an incentive...'

Chautala even imputed motives to the EC fixing a particular date for the counting of votes, and hurled abusive epithets at then Chief Election Commissioner T S Krishnamurthy to the effect that he had lost his 'mental balance' and knew 'only to count currency notes and not votes'.

In both instances, the chief ministers backed off when the EC made them wise about its powers, derived from its omnibus authority under Article 324 of the Constitution, buttressed by judgments of the Supreme Court, to suspend the officers concerned and even to countermand the elections, if need be.

Actually, in 2006, when the Tamil Nadu government got a judgment from the high court against the EC's directive to transfer the then Chennai police commissioner R Nataraj, for showing a 'positive leaning towards a particular leader of the ruling party', the EC, through a special leave petition before the Supreme Court, reasserted its power to 'direct transfer of officials involved in election related work for the conduct of free and fair elections'.

In 2004, the EC had no hesitation to condemn the inflammatory abuses hurled by Biman Bose, the Left Front chairman, against the poll observers appointed by it, and have an First Information Report filed against him.

This step, combined with a notice to the Communist Party of India-Marxist warning it of derecognition, duly brought about a quick retraction by both Bose and Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee, the then West Bengal chief minister.

The latest (April 17, 2013) judicial pronouncement on the EC's authority and competence is that by the Karnataka high court in a case in which eight IAS officers got the EC's transfer orders quashed by approaching the Central Administrative Tribunal. It is by far the clearest and the most categorical affirmation of the EC's power, holding that the EC was not bound to follow the IAS (cadre) rules as it did not pertain to elections and did not govern the utilisation of IAS officers during elections.

Quoting a judgment of the Supreme Court, the high court said that 'in case where the law is silent, Article 324 of the Constitution is a reservoir of power for the EC to act for the avowed purpose of having a free and fair election.'

It also unequivocally laid down that the EC had the power to direct the government to transfer officials to get officers of its choice on deputation, and that there was no obligation on the part of the EC to give reasons for transferring officials as it was doing so for discharging its Constitutional responsibility of holding free and fair elections to preserve democracy.

In the light of these precedents, the EC should come down heavily on the latest outburst, mindful of the Supreme Court's clear-cut call in the Mohinder Singh vs Election Commission case: 'The framers of the Constitution took care leaving scope for the exercise of residuary powers by the Commission in its own right, as a creature of the Constitution, in the infinite variety of situations that may emerge from time to time in such a large democracy as ours. Every contingency could not be foreseen or anticipated with precision. That is why there is no hedging in Article 324.'

'The Commission may be required to cope with some situation which may not be provided for in the enacted laws and the rules... Where these are absent, and yet a situation has to be tackled, the CEC has not to fold his hands and pray to God for divine inspiration to enable him to exercise his functions and to perform his duties or to look to any external authority for the grant of powers to deal with the situation...'

Do you think the political class would have learnt its lesson from the Mamata episode? Not by any length of chalk. Wait for the next outburst.

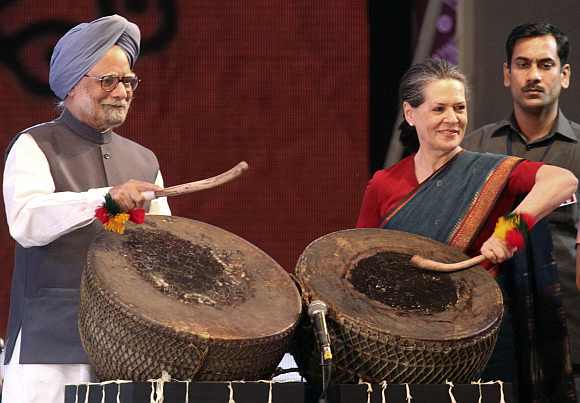

Image: Chief Election Commissioner V S Sampath, left, and West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee.