'There is a compulsion to look hard, decisive, and risk-taking; start something; and then conclude it in a way you can claim victory.'

'That is not such an easy option against China,' notes Shekhar Gupta.

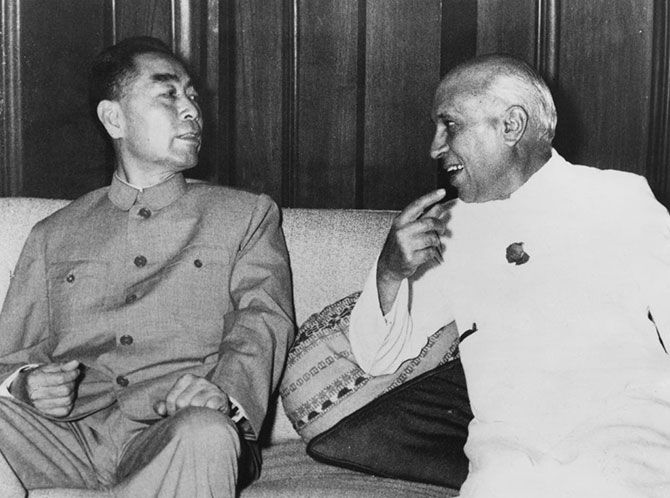

As Mao did to Jawaharlal Nehru in 1959-1962, Xi Jinping has thrown at Prime Minister Narendra Modi the biggest challenge in his public life.

Over the next few days, weeks, months, and years, he will take decisions that determine the strategic fate of his nation. And his own political legacy.

Reading his mind is an act of daring.

Over these six years he has built a formidable reputation of delivering the most stunning surprises, without anybody having an inkling.

Even on crucial strategic and foreign policy issues.

Remember his sudden stopover in Pakistan on his way back from Kabul.

Gaming his responses over the Chinese provocations in Ladakh is complex, but there are pointers.

So, for once, we can read the main question on his mind as he weighs strategy and politics.

Simply put, demand that he must respond, but not in a way that looks like Nehru.

The politics and strategic, philosophical and ideological thought he and his ideological and political parents, the RSS and BJP, have constructed is founded on not being like Nehru.

The most important thing then is to 'not repeat his waffling blunders'.

Mr Xi has thrown the gauntlet at him at the moment of his choosing, just as Mao had done in 1962.

The pressure on him is to respond immediately, in anger, and exasperation just to be seen to be doing something, as Nehru did.

Translated: How to show fellow Indians and the world that you are not Nehru of 1962, without doing precisely what Nehru did under pressure in that fateful year.

Nehru took a decision ('I have told my army to throw out the Chinese') that might have looked brave, but was divorced from reality.

History has judged him harshly.

Not as a brave, tough leader who 'died' fighting, as politically and physically he never recovered from that decision.

He will forever be seen as a weakling who went to war against his conviction.

In 2020, Mr Modi has many advantages.

His political environment has no resemblance to that of Nehru, whose greatest critics were the nationalists within his Cabinet.

Mr Modi has no such problem.

The Opposition is weak, Parliament is no threat, and the armed forces in an enormously better state, despite the PLA's modernisation.

He, however, shares one weakness with Nehru: A larger than life public image, and a thin skin.

That is what Mr Xi has seen as an exposed flank.

From Chumar to Doklam to Pulwama, the Chinese have noticed how vital a factor 'face' is for Mr Modi in his domestic politics.

There is a compulsion to look hard, decisive, and risk-taking; start something; and then conclude it in a way you can claim victory.

That is not such an easy option against China.

What motivated Mr Xi to initiate this confrontation is not so relevant any more.

It doesn't matter because the Chinese are now at our doorstep.

And from the way they are digging in and hauling in heavy equipment it's clear they look prepared for the long haul.

It takes Mr Modi back to the dilemmas all his predecessors have faced.

Is India fated by geography and history to endure a two-front situation?

How can India change this?

Can it reach out to either of the two, and break out of the triangulation? If so, which one?

And third, if it has no way out, or until it has a way out, can it still remain essentially non-aligned?

For clarity, if you give up that pretence and align with any big powers, you cannot also hold on to Cold War notions of strategic autonomy.

Can you trade it for better security?

Every choice involves compromises. Mr Modi has to pick one.

Nehru junked his inflated notions of non-alignment and reached out to Kennedy's America for help in 1962.

Help came, and he permitted the Americans to even set up a military mission, headed by a two-star general, in New Delhi. This came at a price.

The Western powers dissuaded Pakistan from taking advantage of India's predicament in October-November 1962, but in December, Sardar Swaran Singh was negotiating under duress with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto on Kashmir.

This was in return for Western support.

Swaran Singh stalled and as Nehru declined and Kennedy was assassinated, the American opportunity was gone.

India swung Centre-Left again.

Indira Gandhi was sharper.

In 1971, when the Bangladesh opportunity came, she knew she could win only if something could keep China off India's back.

She signed that Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union, which was a euphemism for a strategic alliance.

It gave her those few weeks' leeway to finish the war.

A leader's isn't an easy place to be in.

The substance of strategic and foreign policies is less pretty than the summits.

Rajiv Gandhi, Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, and Manmohan Singh grappled with the same challenge.

None had the political capital Mr Modi does.

All made at least one effort to reach out to Pakistan and break that triangulation.

We had recounted a prescient tutorial by Manmohan Singh on how it was better for India to reach out to Pakistan for peace to deny China this low-cost strategic counterweight.

Mr Modi too made a dramatic flourish with Nawaz Sharif and then gave up too soon.

Pathankot, Gurdaspur, and other betrayals happened for sure.

Great leaders distinguish the tactical from the strategic.

As things unfolded subsequently, he and his party built their politics on anti-Pakistanism.

Terrorism became the pre-eminent strategic threat in our nationalist imagination.

Pakistan-terror-Islam became the three prongs of the BJP's electoral proposition.

Mr Modi tried to break out of the same triangulation that his predecessors grappled with and failed.

But he reached out to China instead, celebrating its leader,/strong>, ignoring its provocations, and welcoming its investment, and looked the other way while the annual trade deficit grew to $60 billion.

This, when his economic nationalism won't let him sign even a tiny trade deal with the US.

The calculation was to give China a vested interest in peace with India.

Mr Xi has now shown that the world's deputy superpower doesn't weigh its strategic interest in trade surpluses.

The idea of isolating Pakistan by reaching out to its allies, China on the east and the Arab world on the west, was creative and audacious.

It failed as Mr Xi won't play ball.

Mr Modi is back to the same three choices: Align with a big power, make peace with one of the two neighbours, or keep fighting on two fronts, in the manner of ekla cholo re.

What about a combination of the first two?

The unipolar world is now over. As is non-alignment. China is the other pole as the Soviet Union used to be.

It has no incentive in settling its borders, not even delineating the LAC, with you.

Peace between two antagonists is possible only when the bigger power wants it. For India, Mr Xi's China isn't that power.

So, the question: Can Mr Modi swing back to where India is the stronger power that wants peace with Pakistan? Much as you may detest Pakistan, it is also more prone to global, especially Western, influence.

Especially when it is an economic basket case.

There is also a shared global interest in moderating the nature of the Pakistani polity.

It can't happen overnight.

But if you do set yourself on that course, it would necessitate adjustments in your domestic politics.

The tricky call then: Does your electoral politics drive your strategic choices, or the other way around?

The platter, or the thaali of choices before Mr Modi, is the old one.

Nehru chose the worst, Indira Gandhi the right but temporary one, Manmohan Singh tried a third but didn't have time or political capital.

By Special Arrangement with The Print

Production: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com