'India in 2020 is a lot better prepared than in 1962.'

'It is no longer a pushover; and anything other than a crushing Chinese military victory will be a major loss of face for China,' observes Rajeev Srinivasan in the first of a three part column.

The ongoing India-China standoff on the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh has such complex antecedents and consequences that commentators have articulated a number of scenarios.

At the moment, the situation is so volatile that we don't know which is likely to play out, but it's worth taking a look at several different perspectives to see the big picture.

Here is my list (undoubtedly not comprehensive):

1. 1962 redux, with China seeking to 'teach India a lesson' and put it in its place as an inferior power in Asia, no danger to Chinese hegemony.

2. India's infrastructure push on the border to be nipped in the bud before it threatens Chinese interests in Pakistan and the Belt and Road Initiative.

3. The skirmish is a tactic to force India to take potential Chinese reactions into consideration and to self-censor itself into paralysis.

4. It's time for India to become a formal US ally and use Quad power to contain China because this is no longer something India can handle alone.

5. The USSR collapsed as the result of opening too many fronts and imperial overreach. Their mis-step in Afghanistan can be compared to China's misadventure in Ladakh.

6. Power rivalry can be modeled as a game-theoretic Prisoner's Dilemma repeated many times. India is following the standard tactic of 'tit-for-tat'.

7. The Rg Vedic tale of Indra slaying Vrtra the dragon and releasing the waters it had dammed seems eerily appropriate.

1962 redux

This the conventional wisdom scenario.

It makes sense based on the fact that Communist-ruled China has been an incorrigible irredentist power, and has swallowed territories that are three or four times as large as its original landmass (which is the core Han territory on the eastern seaboard and points inland).

Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, East Turkestan (Xinjiang), Gosthana (Aksai Chin), have all been conquered through force of arms.

The same salami-slicing tactics are being applied to the South China Sea now.

The good folks at Stratcepts have written a paper on this very topic, China teaches India a lesson where they argue that India has in fact learned its lessons.

India is now conscious not only of 1962, but also 1967 (Nathu La and Cho La), 1979 (China's disastrous incursion into Vietnam), 1986 (Sumdorong Chu) and 2018 (Doklam).

These lessons may not end well for China.

China has a historic tradition of seeking lebensraum for its large population, since it is burdened by poor land and ravaged by natural calamities such as floods and typhoons.

Thus the waves of Han Chinese migration all over Indochina, and the settling spree in Chinese-occupied Tibet and East Turkestan.

It is an article of faith in China that it is the natural hegemon of Asia, and that all other powers need to kowtow to it.

Before 1962, to be fair, China gave every indication of its intention to attack India for two reasons: One, to assert the power hierarchy it perceives in Asia, and two, to gain access to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf through Pakistan.

India chose to ignore the signals because of the then-prevailing 'Hindi-Chini bhai bhai' miasma, much to our cost.

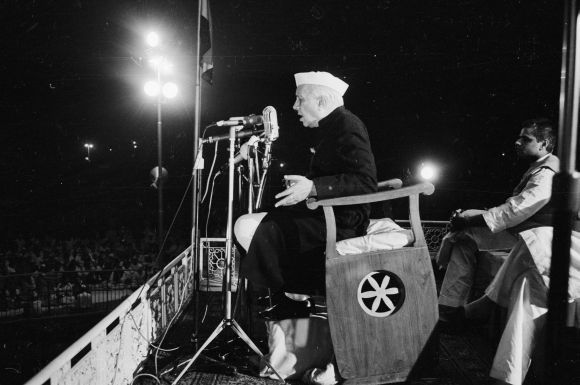

Jawaharlal Nehru was living in some sort of fantasy world regarding the Chinese.

In a 1964 interview, he gave three reasons for why China had invaded in 1962:

1. The Dalai Lama is here.

2. They wanted the Asian world realize they are the top dogs in Asia.

3. They consider all others as uncivilised compared to others.

Perhaps. The only realistic reason is number 2, above.

Not understanding the Chinese mentality, Nehru wasted much blood and treasure in a war which he could have won, if only he hadn't made the unfathomable decision to not use Indian air superiority at all in the conflict.

Today, a vastly more powerful China, with a strong economy and military, perceives that it needs to 'punish' India for a variety of misdeeds: India refused to buy into the Belt and Road Initiative; is improving its connectivity and military infrastructure in the Himalayas; has signaled its intent to take back Pakistan occupied Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan via the abrogation of Article 370; and is involved in the Quad with Japan, Australia and the US.

The fact is that China has, in bad faith, refused to settle the Line of Actual Control by the expedient of endless 'talks' (22 or so rounds so far).

It calculates that time is on its side, as the power differential with India will continue to grow in its favour, and India can be sweet-talked and benumbed while China builds up its fortifications, mountain divisions and air power in Tibet.

All this has been obvious, and I said as long ago as 1997 in a column "The dragon and the elephant" that India needs to be extremely vigilant about the long-term machinations of imperialist Chinese rulers.

That India has not paid enough attention means that our foreign policy and defence mandarins have not done their job well.

In 2020, there is also the threat of a 2.5-front war.

In addition to the usual saber-rattling from Pakistan, we also have a new factor: Nepal's sudden cartographic aggression, deeming Indian territory to be theirs (while it appears that China is grabbing Nepali land by removing boundary pillars and pushing the Tibet-Nepal border inwards a hectare here and a hectare there).

Not surprisingly, Pakistan is reported to have put its troops on alert.

After all, the LOC to the LAC is not far.

A number of commentators have seen fit to take this argument that the game is over to its logical conclusion: that India should just throw in the towel.

Writing on the popular national security blog WarOnTheRocks, two US academics, basically wrote off India's chances 'India's Pangong Pickle: New Delhi's options after its clash with China'.

According to them, India had better accept the inevitable defeat, as China is just too strong, omniscient and omnipotent.

In The Times of India, author Chetan Bhagat wrote a piece titled 'Get peace in return: 'Face' is very important in China. Allow the Chinese to save face'.

Pravin Sawhney, a journalist, tweeted: 'Make peace and adjustments with geography. China will not accept Ladakh UT -- it is very clear. India to decide what cost it is willing to pay for upholding ideology over national security!'

Somewhat bafflingly, retired diplomat, foreign secretary and former ambassador to China Nirupama Menon Rao tweeted: 'If I read China's actions correctly, she is more than ready to burn all boats with India and is just waiting for us to make "strategic miscalculations" (her words) before doing so.'

"In short, we should use diplomatic means to facilitate an agreement between the two militaries to achieve disengagement in areas where the Ladakh LAC is subject to overlapping interpretations."

These are the same tired old bromides that India has been hearing since well before 1962.

That it has to pay attention to China's tender sentiments and not allow it to 'lose face'.

That India must step aside and allow China to get the membership of the UN Security Council that was offered by both the Soviets and the US to India.

That India has options that are bad, ugly and downright suicidal in pushing back militarily on China.

It is good to have these perspectives aired, but the problem is that they reflect a byone era: of appeasement in the belief that China will respond to friendship with good behavior, and that going up militarily against China is simply suicidal for India.

There is only one flaw in the argument: India in 2020 is a lot better prepared than in 1962.

It is no longer a pushover; and anything other than a crushing Chinese military victory will be a major loss of face for China, based on expectations set.

Even a draw is a win for India.

India's infrastructure push and impact on Pakistan, CPEC and BRI

The China Pakistan Economic Corridor is probably the most important project in the BRI.

The entire viability of the BRI is in question now because of the 'debt-trap diplomacy' angle, wherein the donor countries will never be able to pay off the high-interest debt they owe China, and consequently end up having to surrender their strategic assets, as happened to Sri Lanka with the Hambantota port.

If India were to act in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK), the CPEC would be in jeopardy, as the highway cuts through that disputed territory, and is in places only 100 kilometres away from the current Line of Control.

A possible Indian (armored) thrust into PoK would make the CPEC unviable, thus leaving China with massive loss of face.

The current furious Indian road-building activity in the border areas, along with the raising of mountain divisions, suggests that India is now prepared to defend the Siachen glacier (which, let us remember, it appears the Manmohan Singh government was on the point of giving part ownership over to Pakistan in the futile pursuit of 'peace') and not cede unilateral control of the Karakoram Pass to China.

The Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie road appears to be a bone of contention, as this 255 kilometer all-weather road (it took the Border Roads Organisation almost 20 years to build) connects Leh to Daulat Beg Oldie, and parallels the Line of Actual Control and China's strategic Tibet-Xinjiang Highway G-219.

DBO is the only airfield in the region, and retired Air Marshal Barbora recalled recently how he reopened it in 2008 ignoring the orders of the Manmohan Singh government.

DBO, which can handle large transport aircraft like the C17 and C130, is key: It makes it easier for India to resupply its troops in case of conflict.

The biggest potential loser in all this is Pakistan, and therefore it is quite possible that the current Chinese transgression has been instigated by their GHQ, Rawalpindi.

Psychological warfare to make India pause before taking any steps

One of the standard tactics used by China is 'unrestricted warfare' as in the book of the same name written by PLA colonels a few years ago, and so they will use anything at all -- trade, terrorism, river bombs, dams, embargoes, fifth columnists, hackers, you name it -- when they go to war.

Besides, they swear by Sun Tzu, who suggests that the best way to win a war is to not go to actual war at all, but to defeat the enemy through posturing and barbarians within.

Bruno Macaes, former Portuguese foreign minister and general international affairs savant, wrote in The Times of India that 'nibbling territory isn't the point of it. It is to condition India's mind and tie its hands'.

Most Indians have been conditioned to believe that the 1962 debacle was inevitable; well, it wasn't: It was lost because of criminal incompetence among top officials, and the unbelievable refusal to use air power, where India would have dominated.

Even before 1962, says Claude Arpi in his book on Tibet, the Indian ambassador to China (K N Panikkar if I remember right) had decided that China was going to dominate India, and so he went along with them, possibly in the fond hope that they would be grateful.

This is the prevailing sentiment in India now that China has grown so rapidly in the last few decades.

Indians, deep down, don't think they can win against China.

Thus, there has been a noticeable tendency to keep asking, 'What will China think?' before India does anything. (Of course this is paralleled by other absurd questions like 'What would Gandhi do?', and 'What will white people think?' that seem to paralyse decision-making).

The answer, of course, is to do what makes strategic sense to India, war-game the consequential scenarios and be prepared to meet fire with fire.

Chinese strategists may not realize how things have changed since 1962.

Writing in the South China Morning Post, a retired Chinese air force major general said on June 27: 'If we must fight a war, we must strike quickly and contain the scale in a small and mid-sized war aimed at causing pain to our opponents and hence gaining respect via small wars'.

He added that such a victory would project China's strength to the US and pro-independence forces in Taiwan.

So that's what it boils down to: The ancient Chinese trick of 'kill the chicken to scare the monkey'.

They think India is easy meat, to serve as a warning to the US.

With posturing like this, the objective is to test India's political will to take the hit of a war.

Perhaps China overestimates how much other powers are intimidated by it.

And perhaps how good a fighting force its men on the ground are.

Rajeev Srinivasan is one of Rediff.com's earliest columnists.

You can read Rajeev's columns here.

Feature Production: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025