It would be far more sensible for AAP to build on what they have achieved than to destroy what credibility they have by floating wild conspiracy theories, says Sankrant Sanu.

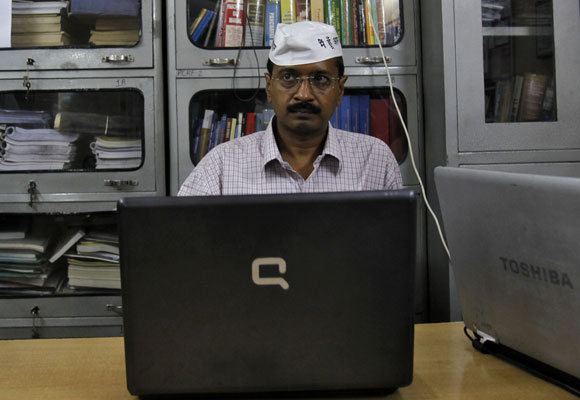

Aam Aadmi Party chief Arvind Kejriwal excels in political theatre.

It was this that built up the hype of AAP winning the election in Goa and Punjab.

An AAP Goa party account tweeted that an 'internal survey' showed they were storming to victory with 41.9% of the vote share in Goa.

AAP's national spokesman Raghav Chadha claimed on national TV that he would resign if AAP got less than 85 seats in Punjab.

In the end, AAP got only 6.3% of the vote in Goa and 20 seats in Punjab.

While all parties show bravado leading up to the elections, most concede gracefully once the results are announced.

However, Kejriwal upped the ante on theatrics where he claimed large-scale tampering in the electronic voting machines may have led to 20% to 25% of the AAP votes in Punjab being shifted to the Shiromani Akali Dal-Bharatiya Janata Party combine.

These kind of wild allegations by a sitting chief minister turn this into dangerous theatre that undermines confidence in the entire democratic process.

They need to be laid to rest.

As someone with a background in computer science, I am quite aware of the limitations of technology. Almost anything can be hacked with persistence.

However, there are several layers of safeguards in the EVM system.

To hack anything, one needs to have access to it, either through a network or physically.

The EVMs are isolated machines, they are not connected to the Internet or any other network.

They are also physically secured, using processes learnt from the much more voluminous storage of physical ballots.

India conducts the biggest elections on the planet, often times in very difficult conditions.

The electoral process has evolved to accommodate that scale and complexity.

While the EC itself has come out to call the allegations of tampering 'wild and baseless', there are other non-technical ways to gauge whether the democratic process is working, at least at a macro level.

The first and foremost is a peaceful transition of power.

While the BJP may have had genuine concerns about the process in 2009 when the United Progressive Alliance retained power, the results of the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 put the concerns to rest.

This is a case when the UPA, which was in power, was swept out all over India, retaining a mere 44 seats.

If widespread EVM tampering were possible by the power-bearers, those results would be highly unlikely.

There are three main power centres involved in the conduct of elections.

One is the Election Commission, which is an independent body; the other is the state government, which supplies most of the local administrative and security support; and the third is the government at the Centre, which appoints the election commissioners and may supplement administrative and security resources.

Finally, the parties and their representatives are themselves closely involved in the process of testing and sealing of the EVMs.

During the Lok Sabha elections of 2014, the UPA was in power at the Centre. Since it had been there for two terms, the election commissioners were also appointed during its tenure.

In Uttar Pradesh, the state that sends most MPs to the Lok Sabha, the Samajwadi Party was in power.

Despite none of the power centres being in its control, the BJP won 71 out of 80 seats in Uttar Pradesh in 2014 with a 42.3% vote share in the state.

The results decimated the Congress whose seat tally came down from 21 to 2 and the Bahujan Samaj Party lost all 20 of its seats. Even the Samajwadi Party tally came down from 23 to only 5.

If large-scale EVM tampering were possible by those in power, the Lok Sabha elections in 2014 would have been the best place to do so, to prevent the BJP from coming to power.

What, then, of the just-concluded assembly elections which the BJP won by a landslide, winning 312 out of 403 seats in UP with 39.7% of the vote. Note that of the three power centres, only the central government had changed from the UPA to the National Democratic Alliance.

Chief Election Commissioner ,strong>Syed Nasim Zaidi had been appointed to the Election Commission in 2012 by the UPA government.

The SP was still in power in UP, exercising strong control over the state administration and police.

Yes, the BJP was in power at the Centre, but even so its vote share is hardly incredible. It actually came down from the 42.3% it secured in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. In terms of seats it had won 71 out of 80 -- 88.75% of them -- Lok Sabha seats in 2014 and won 312 out of 403 -- 77.4% -- of the seats in the 2017 polls.

Of course, assembly and Parliamentary elections are different, but the point is that the voting percentage the BJP got in UP was certainly very achievable; it had obtained a similar result barely three years ago.

Notably, BSP leader Mayawati did not throw around allegations of rigging after the 2014 elections, as she has done now. Perhaps the assembly results jolted her to the possibility of political oblivion.

But she also made the allegations, because the allegations could appear more credible.

As I said earlier, the best test of an electoral system is in the transfer of power.

When the BJP controlled none of the power centres in 2014, allegations of electoral rigging would not have had even emotional credibility, but since it is now the ruling party at the Centre (though it neither controlled the Election Commission nor the state government), the allegations, even if irrational, can carry some emotional weight among her supporters.

Which brings us back to Kejriwal.

Kejriwal has repeatedly been prone to wild allegations including ones in which he was sent to jail as a result of a defamation case filed by Nitin Gadkari.

But his reasons for attacking EVMs, the Election Commission, and the credibility of the entire democratic process by his theatrics, are far more insidious.

When a party claims its 'survey' says it is getting 42% of the vote(external link) but polls only 6%, there are only two real options.

Either it is really stupid to be unable to gauge the difference between a landslide sentiment, which is what a 42% vote translates to, and a barely ran (AAP lost almost all of its deposits in Goa).

Or it was aware of the ground reality, but was outright lying.

Now I don't believe AAP is that stupid. Why would it lie to that extent?

A new party needs to project the real possibility of winning. It needs this to raise funds, enthuse volunteers, get good candidates. It needs to create a buzz.

For all that, some exaggeration is natural.

AAP has also been buoyed by its success in Delhi and has had ambitions of extending it elsewhere.

However, Delhi is really just a city, despite its statehood, although it gets more media coverage because of being the capital and the focus of the national and international media.

This give AAP disproportionate coverage, much more than a regional party -- say, the Biju Janata Dal which is more significant than AAP in that it rules a major state, Odisha -- gets.

This creates hubris and a sense that replicating the Delhi success elsewhere is easily possible.

This exaggerated sense of self and hype gets the party manufacturing, then believing, its own propaganda.

When it all comes tumbling down, like in Goa and Punjab, rather than face reality, Arvind Kejriwal has chosen the easy way out -- to create conspiracy stories of tampered EVMs.

As I said, the BJP's success in UP is easily explained, and it did lose significant seats in Goa and Punjab where Kejriwal alleges tampering.

In the 2017 elections, the Shiromani Akali Dal won about 25% of the vote and the BJP about 5%, down from about 35% and 7% in the 2012 Punjab assembly elections.

AAP alleges the SAD-BJP stole 20% to 25% of its votes by EVM tampering. This would imply the voter base of an old entrenched party in Punjab like the SAD would practically disappear in one assembly cycle. This is hardly credible.

Even the Congress, with all its problems, still got about 19% of the votes in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections.

Also, if a party had the ability and intent to do that scale of tampering, why wouldn't it go for an outright win?

If anything, AAP has had remarkable success in Punjab and even in Goa for a first-time party.

Getting 25% and 6% of the vote respectively is no small feat.

It would be far more sensible for AAP to build on what they have achieved than to destroy what credibility they have by floating wild conspiracy theories, if only to justify their own earlier exaggerations.

Parties are built over decades, not a couple of years.

Getting votes is not like manipulating a Twitter trend for a day.

While he excels at political theatre, perhaps a few steady, mature hands on Kejriwal's shoulder may help the most.

That would be good for AAP, and for Indian democracy.

- Rajeev Srinivasan: How the #DeepState works: Did the Congress 'steal' the 2004, 2009 polls?

- Rajeev Srinivasan: The real issue with Electronic Voting Machines

- Rajeev Srinivasan: EVM row: Shooting the messenger won't help

And DON'T MISS the columns in the RELATED LINKS below...

© 2025

© 2025