K G Subramanyan's artwork had a unique visual language, says Kishore Singh.

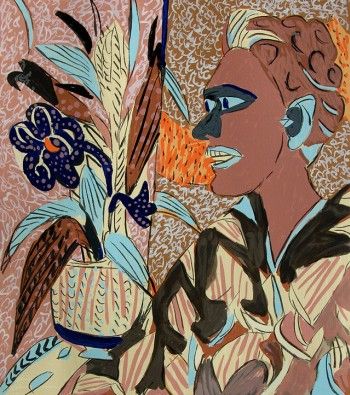

Our Bengali brethren can be remarkably insular with regard to matters of art and culture so when, in a survey of Bengali art, we included K G Subramanyan (left, his untitled work) within their ken and no one objected, it was a signal of the Keralite artist's indomitable acceptance within their ambit.

Our Bengali brethren can be remarkably insular with regard to matters of art and culture so when, in a survey of Bengali art, we included K G Subramanyan (left, his untitled work) within their ken and no one objected, it was a signal of the Keralite artist's indomitable acceptance within their ambit.

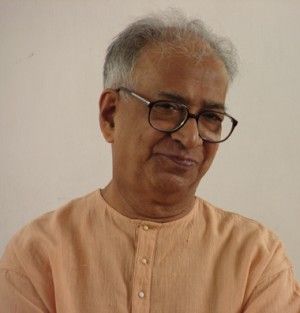

Not only was he an alumni of Santiniketan's greatest teaching triumvirate -- Nandalal Bose, Benode Behari Mukherjee and Ramkinkar Baij -- he also joined the faculty at Kala Bhavana and their ranks, earning in the bargain his Bengali nickname: Manida.

Nor did Subramanyan belong to just Bengal, having also taught at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda, where he went on to create a towering presence within a community of artist-teachers that included the legendary N S Bendre, and as a senior peer of the equally overpowering Gulammohammed Sheikh.

When he passed away in Vadodara (June 29, 2016), he had the comfort of knowing that he was surrounded by Vadodara's community of artists whose regard for him ran uniformly high.

It was a double whammy for those Baroda artists still recovering from the death of a few months ago of another teacher-artist, Jeram Patel.

Patel had made a place and name for himself as a member of Group 1890, a collective of artists who came together in 1962 and held their only exhibition in 1963 under the stewardship of J Swaminathan.

The group's uncompromising attitude towards the dominance of the image over any other context and Patel's refusal to concede to the marketplace turned him into a legend in his lifetime, especially since he didn't waste his breath 'explaining' his work -- which, made with blowtorch on wood, required elucidation for novitiate viewers of art -- preferring, instead, to remain true to his subject.

A forthcoming retrospective at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art will go a long way in establishing Patel's importance on the Indian art scene.

But where his is a difficult, if remarkable, contribution, Subramanyan's has been a delightful and witty one.

Manida revelled in combining completely opposite worlds where it was not unexpected for a multi-armed goddess to come strolling down the road beside a mini-skirted teenager, this juxtaposition raising a few unexpected chortles among the surprised viewer.

A muralist and artist who made reverse paintings in glass, Subramanyan's (left) ability to surprise was his most lasting contribution among the teeming figures he created as part of his universe.

A muralist and artist who made reverse paintings in glass, Subramanyan's (left) ability to surprise was his most lasting contribution among the teeming figures he created as part of his universe.

If Patel's practice was about a negation of space, Subramanyan's was about an affirmation of the absurd, and both held their ground as artists as well as teachers.

They say bad news comes in threes, and the art world is in a state of limbo as another well-known modernist's life hangs by the thread. But there is no reason to get ahead of ourselves even as we glimpse disappearing reflections in a mirror that has taken its toll on a number of artists in recent years.

The presence of the modernists amidst us had been a matter of comfort -- these were artists who changed the course of 20th century modernism in India, no matter what school or collective their owed allegiance to.

Today, they are represented by an ailing S H Raza, the infectious good humour of Krishen Khanna, the retiring Ram Kumar and Mumbai's Akbar Padamsee, upholding the distinctive quality of their vision and voice.

Beyond their ken are the contemporaries who, similarly, have made their mark and etched their own footprints in the cultural firmament.

Just how deeply cast they are in the ephemeral world of art will only be known later when, as in the case of Patel and Subramanyan, we mourn the loss of their passing even as we celebrate what they have left behind for generations to mull or rejoice over.

© 2025

© 2025