'Le Carré's spies were nothing like the exotic Kim of Kipling or the caricature that is James Bond.'

'Driven by a simple patriotism, held back by incompetence and politics, his characters use deceit and treachery to win their morally Pyrrhic victories,' notes P Rajendran.

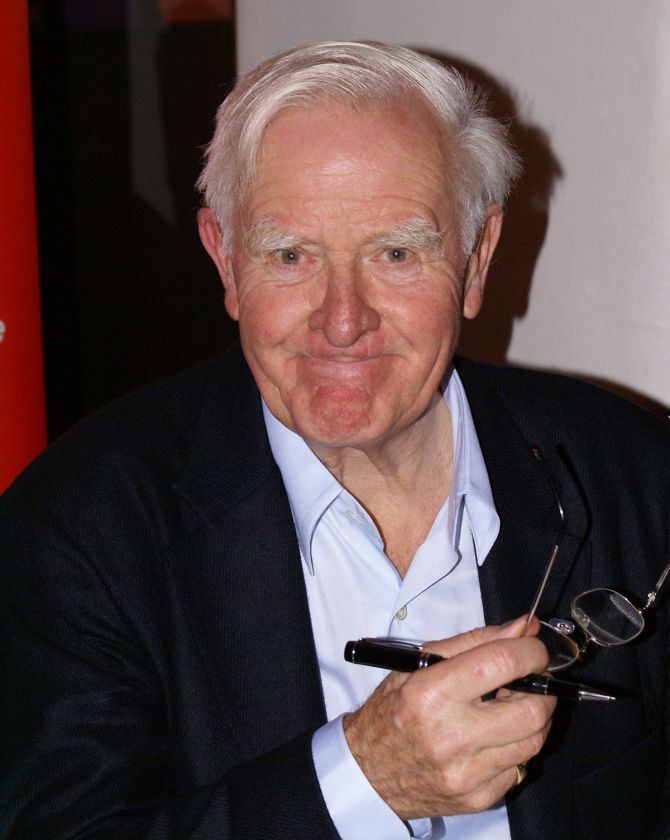

John le Carré was one of the few writers who could make climatic triumphs turn to ashes in one's mouth.

Driven by a simple patriotism, held back by incompetence and politics, his characters use deceit and treachery to win their morally Pyrrhic victories.

With understated ease, le Carré -- born David Cornwell -- wove stories about spies who led humdrum, pointless lives, defined by cynicism, casual distrust and convoluted conflict with no real hope of resolution.

Much of his work seems to draw from his own life.

Le Carré's protagonist was exemplified by the bland and thoughtful George Smiley, who works in a setting defined by petty bickering and tawdry politics, resignedly enduring constant betrayal and defeat, inured to the ultimate futility of winning.

Le Carré's childhood experiences -- and his relationship with an undoubtedly shifty father -- found a fictional outlet in The Perfect Spy.

In The Pigeon Tunnel Stories, he has described his conman father Ronnie, who shifted easily from endearing and untrustworthy love to domestic violence. And yet, Ronnie relied on ingenious, insidious strategies to send his children to good schools he could never attend.

Le Carré speaks of his father's 'episcopal bearing, his ecumenical voice and his air of injured sanctity when anyone dares to doubt his word and his infinite powers of self-delusion'.

Le Carré always harboured memories that are not real and the recollections his father told him were untrue. The fluidity of the truth that defined his childhood made him slow to commit and to search obsessively for the truth.

As he put it in his memoir, 'Nothing lasted: not the Eton schoolmaster, not the MI5 man, not the MI6 man. Only the writer in me stuck the course.

'If I look over my life from here, I see it as a succession of engagements and escapes, and I thank goodness that the writing kept me relatively straight and largely sane.

'My father's refusal to accept the simplest truth about himself set me on a path of enquiry from which I never returned.'

Yet, to his death, le Carré remained another lost boy, always struggling with the loss of a father, one who was often present (except when in prison) and never available for anything more than a doubtfully good time.

Le Carré had a fluid relationship with the truth.

Deviousness came naturally to him since his childhood in a fractious setting.

It was also never actively discouraged at either spy agency that employed him.

But he was ambiguous even when describing Smiley, his recurring protagonist.

Over the years, le Carré kept suggesting different people as his inspiration for the understated, thinking man's spy.

While there may be aspects of all of them in Smiley, and though all fictional characters are both their writers and yet not, main characters do tend to draw a lot from their makers.

Much like le Carré, Smiley went to a minor college and had a wife named Ann.

Jim Prideaux, the predominant character in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, finds refuge as a schoolteacher.

Magnus Pym in The Perfect Spy self-destructively deals with the carnage caused by a conman father.

All the others struggle with trust and dabble in duplicity and lead meaningless lives.

Slimy deviousness defines all their transactions. So, under the tutelage of Russian spymaster Karla, Bill Haydon, a mole in the Circus, the spy organisation where Smiley also works, has an affair with Ann, Smiley's perennially unfaithful wife.

The intent is to cloud the judgment of the fact-obsessed Smiley, to make him unsure whether his doubts about Haydon are spurred by his own desperate jealousy and not actual evidence of malfeasance.

Later, Smiley, showing he is no different, exploits Karla's love for his daughter who is tumbling into schizophrenia, to get him to surrender. A triumph, of course, however hollow.

If le Carré's first novella, Call For The Dead, was comparatively straightforward; despite the incomplete references, the tangential allusions, by The Spy Who Came In From the Cold, he had a spy thriller that Graham Greene could have written. And Greene recognised it as such, despite a falling out later.

Over time, le Carré's writing became even more allusive -- and elusive -- with different critics coming up with different views on what his best book was, varying by the taste for adventure or literary pretensions.

Le Carré's spies were nothing like the exotic Kim of Kipling or the caricature that is James Bond (one only rescued by some deadpan humour in the movies), but is more reminiscent of Somerset Maugham's Ashenden, a spy who also sees the work of spies as ultimately pointless, or perhaps Greene's Alden Pyle from The Quiet American, a well-intentioned man driven by prim certitude to do the worst things possible.

While le Carré's novels show the Cold War Russians as redoubtable but unscrupulous rivals, the Americans -- the 'cousins' -- are depicted over-the-top, bumptious and selfish.

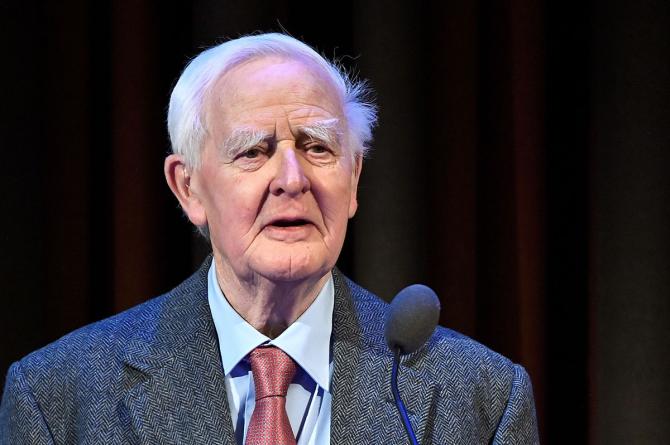

Unlike Smiley, who is dutifully patriotic and reluctantly amoral, le Carre -- Cornwell in real life -- took up strong political positions, at least in his later years, objecting to a variety of Western interventions -- in Iran, Iraq and elsewhere -- and against corporations. The end, to him, did not justify the means.

He expressed doubt and contempt for authoritarians like Vladmir Putin and Donald Trump and took up cudgels against the pharmaceutical industry in his Constant Gardener, even while revisiting many of his older themes in it.

Former US first lady Michelle Obama once described people with power in stark terms: 'Here's the secret: They're not that smart.'

Le Carré uses an allegory to make the point. Early in The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, protagonist Leamas, an angry idealist, just misses hitting a car driven by a wild-eyed, terrified and incompetent father, while his oblivious children laughing in the back.

They are not aware they had just missed being crushed by the huge trucks around them.

At the end of the book, when Leamas is looking down at the body of Nan Perry, the innocent victim of impersonal forces beyond her ken, instead of escaping himself as arranged, he waits till the East Germans have no choice but to shoot him.

The last line of the book is a nod to the idea of the meaningless of leadership everywhere, perhaps even today: 'As he fell, Leamas saw a small car smashed between great lorries, and the children waving cheerfully through the window.'

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025