Pratinav Anil is able to foresee some agency and assertion on the part of India's Muslims.

His hope emanates from the citizenship rights movement of Muslims in 2019-2020, notes Mohammad Sajjad.

Pratinav Anil's latest book, Another India: The Making of the World's Largest Muslim Minority, 1947-77, is an intensively well-researched, yet, a polemical and provocative book.

On the Muslim question in the Indian Republic, Anil is harshly critical against Nehruvian policies and programmes.

He characterises this era of Nehru-Congress hegemony as Islamophobic.

One of the targets of his polemics is Mushirul Hasan's 1997 book, Legacy of a Divided Nation: India's Muslims since Independence, which, according to Anil, is 'an inventory of elite political maneuverings in which Muslims are little more than spectators'.

He puts other scholars such as Rafiq Zakaria, Moin Shakir and Omar Khalidi, in almost the same league.

In his own words, Anil's 'primary aim is to recover Muslim agency'.

Admittedly, he is 'repurposing the minority question to reflect on the majoritarian character of Indian democracy'.

Thus, the tallest of the Congress Muslims are subjects of Anil's bitterest ire.

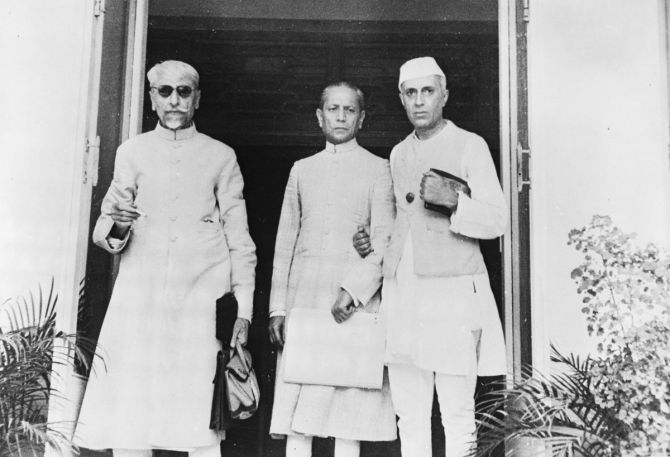

Maulana Azad, Zakir Husain, Rafi Kidwai, Humayun Kabir, Syed Mahmud, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmad, all are left un-spared.

To this extent of 'Muslim agency', Gyan Prakash is more candid in his book, Emergency Chronicle.

'Minorities received equal rights in the Indian Constitution as a result of the nationalist struggle against the British, not due to a specific struggle for minority civil rights.'

Though, Anil, deriving from Paul Brass and Theodore P Wright Jr, says, 'The quintessential dilemma of Muslim politics [is this]: 'communal' appeals asked for trouble whereas 'secular' mobilisation cut no ice.'

Was it because of the politics of guilt and circumspection? Anil's answer seems to be in the affirmative.

Anil has worked harder to dig out archives and find out expressions such as, Lord Wavell, the then viceroy of India, used the expression, 'cheap butter of insincere compliments' for Shafaat Ahmad Khan; Hasrat Mohani, in the Constituent Assembly Debates, dated January 4, 1949, calling the nationalist Muslims as 'slaves of the Congress'; Syed Mahmud, the Nehru's friend, was 'Just like a Dog' of Nehru; even a south Indian Muslim leader like Muhamamd Ismail (1896-1972) is described as 'a snake without fangs'....

As a student of Modern Indian history, I have always been intrigued about the roles of Maulana Azad in the politics of the Shariat Act, 1937 and his roles in the Constituent Assembly Debates (1946-1949).

Anil delves into the latter question rather deeply, wherein Azad cuts a sorry figure in the tales of Anil.

Rizwan Qaiser's 2011 book Resisting Colonialism & Communal Politics: Maulana Azad & the Making of the Indian Nation had demonstrated Azad's loneliness and helplessness within the Congress, notwithstanding the fact that he was the Congress president between 1940 and 1946.

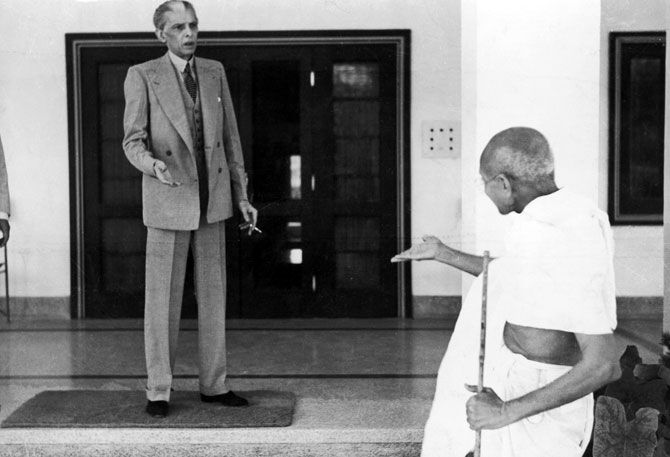

In conformity with the Cambridge School, Anil won't put even a share of blame of India's Partition on the British.

He would say that the Partition 'plan was accepted across the board-reluctantly by Jinnah, nonchalantly by Gandhi, and with both hands by Nehru'.

He thus ends up appreciating communal separatism: 'The League aspired to economic and political [empowerment of the Muslims], nationalist Muslims to cultural and legal, sovereignty'.

This, I think is strange, for, the Shariat Act 1937 was the handiwork of Jinnah.

Nonetheless, Anil does admit, at least this much, that, 'at least in the realm of discourse and high politics, the Congress represented some kind of secular ideal'.

Tirade against Maulana Azad

Anil's tirade against Azad is worth noting, culled by him from across the primary and secondary sources:

Throughout the 1950s, 'the maulana seldom participated in debates in Parliament'. His lawmaking colleagues accused him of prolonged truancy. Whenever his presence was needed, Azad would send in a stand-in.

In 1955, the Times reported that he had absented himself from Parliament for a year now.

He never answered questions, more because of his dipsomania and less because of his arrogance.

Azad's counsel to his Qaum to 'live as loyal citizens', attracts this comment from Anil: 'Loyalty, of course, is not a sign of agency, nor so much a programme, but a demonstration of submission'.

Similarly, in the wake of the 'police action' in Hyderabad [September 1948], Azad tried to explain away the killing of 40,000 Muslims on Delhi's watch before a Muslim audience: it 'was an inevitable consequence of the minority community's misdeeds and excesses. The laws of nature were immutable and every action had its reaction'.

Better than 'crying over spilt milk', he recommended Muslims to steer clear of government and work towards the 'rehabilitation and uplift of their fallen brothers and sisters' themselves.

For 'in a large measure' this burden 'rested with the community' itself, not with the state (Times of India, September 30, 1952).

The choice of words, it hardly needs telling, hinted at reduced agency, says Anil.

'To Azad, then, there existed a neat separation between the political and cultural. The former needed to be relinquished, the latter defended.

'For nation-building depended on unity, and while there could be unity in cultural diversity, political differences could be fatally divisive. This was the lesson of Partition.

'Better then to take up the cudgels for the Congress, circumscribe demands, and concentrate energies on cultural concerns -- as we have seen, the holy trinity of nationalist Muslim thinking.

'Early postcolonial Muslim politics was immeasurably shaped by this worldview... its upshots were most forcefully felt in the Constituent Assembly [Debates], where nationalist Muslims exchanged political for cultural safeguards.'

'The goodwill earned by the nationalist Muslims in the summer of 1947 by consenting to the scrapping of separate electorates, then, had by early 1949 become a wasting asset...,' Anil adds.

Four months later, on May 11, 1949, Patel's supporters mounted an attack on the qaum's sole remaining safeguard: Reservations.

Azad had defended parliamentary quotas in July 1947. Now, in the Constitutional endgame, the maulana made a stunning volte face.

Whether this was elicited under duress we will never know. But what we do know from the [K M] Munshi Papers is that when the question cropped up in the committee, 'the representatives of the nationalist Muslims sat silent'

'Azad, apparently, 'had instructed them not to press for reservation'.

'Here, again, silence was submission by proxy.... At first blush, Azad's silence is surprising in view of his position in four of the eight major assembly committees, not to mention his distinction as the party's longest-serving president.

'All the same, figures like the maulana may have been important men, but they also tended to be self-effacing, and, appropriately enough, they were often effaced.

'Therein lies the rub for the historian: To write about the nationalist Muslim is to be repeatedly confronted with the silence of one's subject, the uncovering of their agency a journey through so many cul-de-sacs'.

Even while debating due process of law on preventive detention, Azad is said to have remained silent.

It was Sadullah who argued that this was invoked mostly against Muslims. According to Anil, his silence was to please Nehru and Patel. Though, B N Rau was of the opinion that it was undemocratic.

Anil also reveals that the Congress used ex-Leaguers Begum Qudsia Aizaz Rasul (1909-2001), 'the poster-girl of secular Muslims', and Tajammul Husain (Shia landlord from Bihar) to silence the likes of Azad on the issue of political safeguards. Humaira Chowdhury's essay (2021) reveals even more on that.

'Her [Aizaz Rasul's] vehement opposition to separate electorates and reservations for Muslims and women speaks of an ambivalence regarding what it meant to be a religious minority in the post-colonial context, which in turn mirrored the ambiguities surrounding the meaning of secularism in independent India'.

On the language question too, 'Azad resigned from the language committee over the impasse. 'I would like to tell you that by accommodating Urdu the heavens will not come down', he tearfully lamented in the assembly.'

Anil explains to us why and how did the Muslim politicians of all hues kept the Shariat politics ('juridical ghetto') at the centre of priority and a resultant depoliticisation of the power-obsessed Qaum.

In this regard, Anil is particularly critical of the UP Muslim elites not only in late-colonial era but also in the post-Independence era. 'Indeed, what they achieved through their spirited defence of the Sharia was unique in world-historical perspective.

'At a time when Islamic laws were being torn up, or radically rewritten at the very least, across the Muslim world-Pakistan, Morocco, Libya, Lebanon, Tunisia, United Arab-in India, Muslim Personal law remained untouched'.

Anil's diagnosis about the competitive communalisation of India's socio-political landscape in the 1980s is persuasive.

'If the Hindu leadership disregarded the material interests of Muslims, so, too, did the community's ashraf leadership.

'After Ayodhya, more bile was directed at the Ahl-i-Hadith ulama, whose 1993 fatwa declared triple talaq un-Islamic, than at Hindu nationalists.

'To the delight of the JUH and AIMPLB, the schism was short-lived. Orthodoxy prevailed. Taqlid trumped ijtihad -- purblind conformity trumped creative interpretation'.

This, Anil says, went on to 'furnishing Muslim men with a private fiefdom to do as they pleased was poor recompense for their despondent public existence in an Islamophobic society'.

In this vein, it is unsurprising and quite predictable about Anil's take on Syed Shahabuddin (1935-2017), the diplomat turned politician, who, along with the Muslim Personal Law Board, was one of the main actors to have nationalised the hitherto localised issue of Ayodhya.

Does Anil prescribe against the politics of victimhood when he talks of recovering Muslim agency?

Did the prescriptions of Muslim modernisers such as M C Chagla and Hamid Dalwai help?

What about the India's Islamists and clerics, against whom K M Ashraf (1903-1962) and Mushirul Haq (1933-1990), besides M Shafi Agwani (1928-2018), have written rather more frankly?

Anil's comprehensive and penetrative take on capitulations and strategic transformations of the Jamaat-e-Islami-e Hind is interesting.

As it is throughout the book, he 'blames' the Nehruvian phenomenon, for having tamed the JIH to become 'Almost Liberals', who 'remained firmly grounded in anti-political thinking', in pursuit of 'theodemocracy'.

For other brands of post-independence Muslim politics too, Anil 'points to a peculiarity of the Muslim political classes. They have always excelled at counting heads and securing sinecures. Equally, they have always failed at directing policy. Spectacularly so'; and, that their 'style of politics' was 'premised on pledges and charters, rather than parties and cadres'.

Yet, Anil ends the book on an optimist note. He is able to foresee some agency and assertion on the part of India's Muslims.

His hope emanates from the citizenship rights movement of Muslims in 2019-2020.

Notwithstanding some limitations, Anil's book is an important intervention; too many of French language expressions and use of uncommon, at times inapt, English vocabularies make the read little cumbersome.

Being provocative and polemical it will attract a wide cross section of readership.

Mohammad Sajjad teaches Modern and Contemporary History at Aligarh Muslim University and is the author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge 2014/2018 reprint).

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025