'Indian nationhood is indeed at the cusp of alarming redefinition -- hate-filled, and exclusionary.'

'Nations are not built this way, instead these are the ways of liquidating nations.'

'We must pre-empt it.'

'Can we?' asks Mohammad Sajjad.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

The growing hatred and violence against Muslims and the spectacularly video-graphed circulation thereof, in the India of today, has acquired an ominous frequency.

It is increasingly making us inured, as such barbarity becomes the new normal.

Does it have an explanation, at least partly, in our history, and history-writing?

History rarely repeats itself. Nevertheless, if we are to understand what is happening in the polity today, it is useful to look into the past.

Today's India, witnessing powerful and aggressive majoritarian chauvinism, has some eerie resemblance with what was happening between 1938 and 1946, under the colonial regime.

Part of the reason of the hatred against Muslims in contemporary India is the way in which the causes of India's Partition have been explained, and popularised through government textbooks.

Too much guilt and villainy has been placed on the Muslim League which has been read by deleting the suffix, 'League'.

In the last few decades, research emerged exposing majoritarian communalism within the lower Congress, and outside it, where it was assertively articulated by the Hindu Mahasabha-Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh post 1938.

But the question is: How many Left-controlled/dominated academic journals in India even reviewed such works?

In fact, such expositions have been almost proscribed, censored, ignored.

Even the Indian History Congress did not include any such work in its award-winning lists.

On the other hand, the one reiterating Muslim separatism (Venkat Dhulipala's Creating A New Medina, 2015), has been given too much of media hype and lauded by the liberal-Left historians of India's major cities.

Today, the liberal-Left segment of scholars and opinion writers also need to subject themselves to self-introspection on this count and to revisit Partition historiographies.

If one cares to look at the political developments in various provinces post 1924 and post 1938, it clearly emerges that as the Muslims began to register their rising representation in local bodies and provincial councils, the Hindu-Muslim tussle in these domains of emerging power structures started becoming prominent.

This is what happened more clearly in Bihar, post 1924. The tallest builders of the Congress began to be marginalised. Mazharul Haq, Shafi Daudi, etc were systematically pushed out of the district boards in the late 1920s leaving them disillusioned.

After 1938 this trend started taking an ominous shape.

The Muslim League accused the Congress ministries in various provinces in 1937 to 1939 to having resorted to the persecution of Muslims, and letting off rioters.

No less than three catalogues were prepared by the Muslim League in 1938 -- the Pirpur report, the Sharif report and the Fazlul Haq report. With this, the League progressed leaps and bounds between 1938 and 1946.

Isn't it puzzling that we do not hear of a similar list of Hindu grievances in the Muslim 'majority' provinces, catalogued by the Hindu communal forces, accusing the 'Muslim' ministries of those provinces, such as Bengal's Krishak Praja Party, Punjab's Unionist Party, and Assam's Saadullah ministry?

This was unlike the Suhrawardy ministry of 1946 when his culpability over the orgy of violence and killing in Bengal unambiguously existed, creating much anger among Hindus, so much so that it had its retaliatory implications in Bihar.>/p>

The question therefore is: Were those catalogues of 1938 actually as unreal (or exaggerated) as we have so far been given to believe, even by our liberal Left historians?

Is their dismissive-ness, popularised much through popular textbooks, buttressed by the argument that the offer of an inquiry into those grievances by Justice Gwyer was rejected by the Muslim League, and hence the fictionality of those grievances stood testified?

Or, is it a case like today, when the 'nationalist' forces want us to believe that instances of frequent lynching and other such persecution are isolated incidents; that they should not be exaggerated to discredit the incumbent BJP regime; and that the BJP should not be accused of being complicit in creating an atmosphere of fear among the minorities?

Let us recall that the Muslim League was routed in the 1937 elections despite the fact that seats were reserved for Muslims under the arrangement of separate electorates.

Yet, soon after the formation of the Congress ministries fear emerged among the minorities, and the Muslim League could register a rise in its political fortunes after 1938.

There is evidence that many Congress Hindus demonstrated that a 'Hindu Raj' had been restored in 1937, seven centuries after Prithviraj Chauhan was unseated in the 12th century.

Indian historians have paid less attention to the rapid growth and proliferation of the RSS-Hindu Mahasabha after 1938 in the nooks and crannies of India. There have been relatively fewer studies on the Congress-Mahasabha overlap at the provincial and district levels.

Joya Chatterjee's Bengal Divided (1995), William Gould's study of UP (2005), and Vinita Damodaran's (1992) and Papiya Ghosh's (2008) studies of Bihar are among the exceptions.

India's liberal-Left historians received Venkat Dhulipala's study of UP very warmly. It underlines Muslim separatism, just as Francis Robinson (Separatism Among Indian Muslims, 1974) had demonstrated four decades ago.

Whereas William Gould's book Hindu Nationalism and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial India was largely ignored, for it exposed the majoritarian tilts of the tallest Congress leaders of UP -- Purshottam Das Tandon (1882-1962), Sampurnanand (1891-1969), and Gobind Ballabh Pant (1887-1961).

It is surprising that Mohammed Ali Jinnah did not harp as much on these UP leaders while attempting to wean the Muslims away from the Congress and propping up the Muslim League.

Joya Chatterjee has demonstrated that in the 1930s, when Bengal's share-cropper peasantry turned into middle and rich peasantry, they gained franchise, and this is how Muslim representation began to increase in legislative and other arenas.

This is what alarmed the bhadralok who, in order to avert the ignominy of being politically dominated by the Muslim peasantry, slipped towards partitioning Bengal during 1932 to 1947.

Similarly, T C A Raghavan (Economic and Political Weekly, April 9, 1983) for western India, and Vinita Damodaran (Broken Promises, 1992) for Bihar, 1935 to 1946, have demonstrated how Hindus, both within and outside the Congress, moved towards majoritarianism as soon as the middle peasants of the Backwards, Harijans, and Muslims acquired affluence and franchise in the 1930s (particularly after the Gandhi-Ambedkar Poona Pact, 1932).

The peasant discontent was sought to be channelised into religious strife by the landlords.

Justice Reuben (1893-1976; ICS 1918) was not allowed to conduct inquiries into the 1946 riots of Bihar. Yet, India's best known liberal-Left historians, working on these aspects, plead ignorance about Reuben's inquiry.

Overall, both colonial and post-Independence Indian states have been palpably soft on rioters. There have been wilful failures of the criminal justice system in this regard.

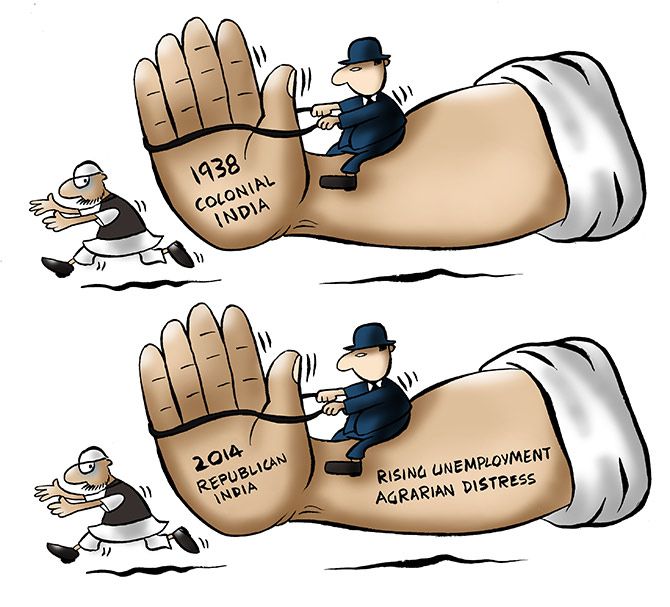

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

With this experience from history, let us now have a look on the developments immediately before 2014 when the BJP came to power with an unprecedented mandate.

In 2012, Muslim representation had gone up in the assembly and municipal bodies in Uttar Pradesh. Muslim representation in the legislative assembly was around 17% close to the Muslim population of 18.5%.

In municipal bodies, there were 3,681 elected Muslims out of a total of 11,816 members, pushing their representation to 31.5%.

This was seen as a 'Muslim upsurge' in Uttar Pradesh, perhaps partly foretelling Yogi Adityanath's rise to power.

In Bihar, where Muslims are 16.5% of the population, their representation among the panchayat chiefs has remained at around 16% since 2001.

In fact, the rise of the saffron forces since the 1980s has much to do with rising Muslim affluence because of Gulf remittances, and the benefits going to its Pasmandas after the implementation of the Mandal reservations in education and public employment, and subsequently into the local bodies as well, besides their entry into local small tradings.

In West Bengal, where Muslims are around 25%, the Hindu bhadralok through Communist rule resisted the temptation to join saffron forces by keeping most of the Pasmanda Muslim communities out of the OBC list till 2011.

Now with their inclusion as OBC, saffronisation of West Bengal is becoming much more visible.

An increasingly bigger segment of the Hindu population is now easily persuaded to be scared of the 'minority upsurge' by misleading them with the argument that, after all, for centuries the Muslims and then Christians (the British) ruled over Hindus despite being a numerical minority.

This oversimplification of a complex historical issue by the communal forces starts making sense to these segments.

This is how hate-mongering politics thrives.

Quite a lot of those now vocal for the BJP on social media belong to those segments.

They feel that because of the Mandal reservations they have not been able to hold on to their pre-eminent positions in education, trading and employment.

The post-liberalisation economy, rising youth unemployment and agrarian distress, have also affected them adversely.

This discontent is sought to be channelled against a demonised Muslims.

There is a growing grudge, scorn and disdain against the rising Muslim presence in all such spheres.

This is now degenerating increasingly into hatred and violence against them.

From urban confines, this has percolated down to rural hinterlands because in rural areas, too, the trading rivalries are sharpening as the kith and kin of the Gulf-based Muslim professionals have erected their trades in rural markets.

The lower class Muslims too have acquired affluence and education. Their presence is increasingly becoming more prominent through lofty masjids and lavish public demonstrations of festivities.

Even though in most cases such competitive public rituals and festivities have more to do with a statement of their coming of age vis-a-vis the historically dominant groups within their own community, and also to outdo the other/rival sub-sects (maslak; more specifically, the Barelvi versus the Deobandi/Tablighi Jamaat and Ahl-e-Hadis).

These are often mistaken as Muslim assertion against Hindus.

This explains the growing insecurity of the traditionally predominant groups of the religious majority, who are trying to counterpoise it through communal mobilisation around religious solidarities, by demonising, and by othering, the Muslims.

This is how the harmonious social fabric has been tattered, resulting in the rise of aggressive Hindutva.

Its resurrection began in the 1980s, and its claws remained less deadly in the 1990s and 2000s, in better parts of India, when the subordinated groups were coming of their age, dislodging the upper castes from power.

The Congress kept compromising with its core principles resulting in losing its support base and eventually getting discredited among almost every segment.

It had given up on Muslims in 1946 to the extent that despite repeated requisitions, the Congress did not even field its candidates from the Muslim seats.

Its lack of sincerity was evident even in its Muslim Mass Contact Campaign of 1938 which exacerbated the situation by alarming both the majority and minority communal forces -- the Mahasabha and the League.

However, unlike between 1938 and 1946, now, post-2014, no Jinnah can emerge with the promise of a separate homeland, as there is no limited franchise now, nor is there a colonial State. We now have universal adult franchise, with all its heterogeneities and stratifications.

Jinnah could outsmart the then regional, peasant-based political formations such as Bengal's Krishak Praja Party, Punjab's Unionist, and other smaller anti-separatist formations such as Bihar's Muslim Independent Party etc, only because less than 11% people of a particular class had franchise then.

Managing and consolidating them may have been easier for Jinnah, exacerbated by the prodding and encouragement from the colonial power.

Even though one may not deny today the power-play of the native and global capitalism of imperial powers in widening the rich-poor gap, which breed and perpetuate identity-based hatred and violence and polarisation.

Two historical moments may or may not find a close comparison. Yet, post-1938 colonial India, and post-2014 republican India, do have very disturbing resemblances.

This is also the alarming issue, that India's Muslims cannot remain 'disenfranchised', pitiably subdued and persecuted.

So, the desperate question is: What will come out of this situation when Muslims are being pushed against the wall?

Shall they remain electorally/politically invisibilised, irrelevant, silenced, subdued and subjugated, and yet demonised by the ruling party; and a liability for the 'secular' parties, as they are in Gujarat today?

Is it a case where only a silenced and subdued minority will satiate and please the communalised majority?

Indian nationhood is indeed at the cusp of alarming redefinition -- hate-filled, and exclusionary. It will validate all the ideas that were behind the vivisection of our country in 1947.

Nations are not built this way, instead these are the ways of liquidating nations.

We must pre-empt it.

Can we?

Professor Mohammad Sajjad is at the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University.

He has published two books: Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours(Routledge, 2014); Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur since 1857 (Primus, 2014)

© 2025

© 2025