'One hopes the younger generation sees Savarkar him for what he was and does not view him through a distorted prism.'

'One hopes the younger generation sees Savarkar him for what he was and does not view him through a distorted prism.'

'This is the least one could do for someone who devoted his whole life to the Indian freedom struggle, elimination of caste, succour to Dalits, and instilling a strategic culture in India,' says Lieutenant General Ashok Joshi (retd) and Colonel Anil A Athale (retd).

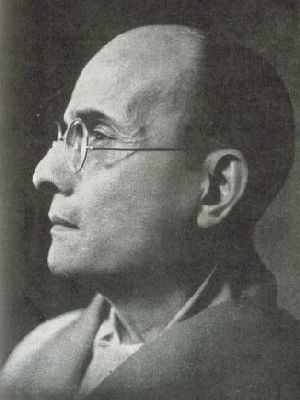

On February 26, 1966, exactly 50 years ago, one of India's greatest freedom fighters breathed his last.

Vinayak Damodar 'Veer' Savarkar's legacy, unfortunately, got mired in controversy mainly because of the tussle between the leftist and rightist forces within the larger Independence movement. He became the pet hate object of the left liberals as well as the Muslim League that spearheaded the demand for Pakistan.

Over time, his contribution to the national cause was denied and he was virtually rendered persona non grata or worse in the eyes of many who took their cues from the then ruling party.

Most of his writing is in Marathi and hence not easily accessible to readers outside Maharashtra, giving rise to many misconceptions about him. This article is an attempt to put forward evidence about various facets of his eventful life and personality before the younger generation.

In recent times of divided opinion, it has become fashionable to label admiration for Savarkar as being anti-Mahatma Gandhi. This need not be so; both were patriots who in their own way struggled for Indian Independence.

No other leader of the freedom struggle was as vilified as Savarkar. Subhas Chandra Bose or Vallabhbhai Patel were not given their due either and ignored until recently, but dislike of Savarkar had been assiduously cultivated and propagated.

There were three main reasons for this: His strategic outlook; his 'Hindutva' thesis; his fundamental differences with Gandhi.

Savarkar believed in adopting all means including force to attain the national goal of complete and total Independence. He urged Indians to join the army at the outbreak of the Second World War so that the Indians could eventually turn on the British and throw them out.

Learn the art of soldiering from the British, and then turn on them when ready was his philosophy. The shorthand for this that he used was 'militarisation.' His appeal to Indian youth to join the armed forces during World War II was deliberately distorted.

Colonel Athale has personal knowledge of this issue as his father, the late Anant Athale, who had taken part in underground activities earlier, was one of those who heeded this call and joined army training. There are a few Indian Army officers alive who had joined the armed forces with this aim.

The British got a taste of what was likely to happen when in February 1946 they faced a naval mutiny against their rule. Clement Atlee, the then British prime minister, is on record that the Indian National Army activities and the naval mutiny were the main reasons for granting India independence.

Savarkar's advocacy brought him into direct conflict with the Congress that had launched the Quit India movement. In contrast, Mohanmmed Ali Jinnah had endeared himself to the British by supporting the war effort, which the British were bound to reward.

Savarkar warned the Congress that its Quit India movement would turn ultimately into a Split India movement. Unfortunately, he proved to be prescient.

This might have hurt the Congress the most because the onus of Partition, no matter how farfetched, had to be shaken off. No wonder the dislike of Savarkar increased exponentially thereafter.

Savarkar had been sent to the Cellular Jail in the Andamans in 1910 to serve a sentence of 50 years of hard labour. Although he was shifted to India in 1921, he was kept in various jails until 1924. Even after release, he was kept under one restriction or the other until 1937.

A keen and perceptive student of history, he had concluded that the absence of geographical-cultural nationalism in the Indian subcontinent had led to the slavery of India for centuries.

So, along with militarisation, he made the concept of Hindutva a cornerstone of his political philosophy. He propagated that every Indian must regard the subcontinent as the ultimate repository of all his loyalties, without reservation.

Therefore, he called for faith and commitment of all Indians to undivided India. The Congress felt that this buttressed the two-nation theory and opposed Hindutva.

Veer Savarkar was a patriot to the core since the tender age of 12. But unlike Gandhi, he neither believed in Ahimsa nor Satyagraha to attain Independence. He instead believed that a violent struggle was the only means to secure freedom from the British yoke.

Savarkar had looked upon the freedom struggle as an unending war, and to him everything was fair for so long as he could get at the Imperial power. He was not bound to tell the truth to his enemy. He was not a satyagrahi, he was a warrior, and had no compunction in practicing deceit with the British rulers -- incidentally, 'truth' is not a principal of war, but surprise is.

Savarkar was not an orthodox man and did not believe in Chaturvarnya (the four-fold Hindu caste system). He regarded untouchability as part of the seven shackles that kept Hindus and India weak. He advocated inter-caste marriages and was one with Babasaheb Ambedkar on abolishing castes.

Where he differed with Ambedkar was on issue of religious conversion to fight caste.

On April 14, 1942, on the occasion of Ambedkar's 50th birthday, the following message was sent to him by Veer Savarkar: 'With his personality, learning, skill in organisation and capability of giving leadership, Ambedkar would have become a great mainstay of the country today. The success he achieved in eradicating untouchability and infusing self-confidence and spirit among untouchables was valuable service to India. His work is of eternal nature, humanitarian and that of imbued with pride in one's own country.'

Savarkar fought for Dalit entry into temples and built a temple in Ratnagiri where he appointed a Dalit priest. He was of the firm belief that unless Hindu society got over caste discrimination, the country could never progress.

His speech at a Ganesh festival in a Dalit locality is worth reproducing:

'I wish I would see untouchability removed in my lifetime. After my death may those giving shoulder to my coffin comprise businessmen, Dhed and Dome (the so-called low-castes), apart from Brahmins. Only on being consigned to flames by them will my soul rest in peace.'

He was on the same page as Dr Ambedkar when it came to eliminating caste prejudice and disadvantage.

Savarkar wanted modernity, technology, machines and industry. He was a worshipper of power. The Mahatma wanted the spinning wheel and village industry as routes to progress. Savarkar was no cow worshipping traditionalist.

When asked about cow slaughter and beef eating, his answer was, 'The cow is a useful animal, neither more nor less.'

He embraced modernity and wanted all old traditions tested against logic and usefulness. In this sense he was closer to and an admirer of Jawaharlal Nehru's policy of industrialisation and inculcation of scientific temper.

The differences that he had with Gandhi were just too many and Savarkar took up issues with him. He was a fiery orator, and his political meetings after 1937 attracted huge crowds. He highlighted his differences with Gandhi in scathing terms and left no one in any doubt.

This approach brought Savarkar into further conflict with the Congress. And the party decided to diminish him. No wonder that he was later implicated in the conspiracy to murder Mahatma Gandhi.

Dr Ambedkar, then the law minister in Nehru's Cabinet, had revealed to Savarkar's lawyer that Savarkar was implicated in the trial on the flimsiest of grounds by Nehru despite the opposition by the entire Cabinet.

Apart from being a fearless man of action, Savarkar also happened to be a philosopher, an outstanding man of letters, and a poet extraordinary. His inspiring hymn to the Goddess of Freedom written, in Sanskrit and Marathi, is popular to this day. It is not only sung on public occasions, it is set to music and played by military bands.

Savarkar was the first Indian to conclude that the 'mutiny' of 1857 in India was in fact a war of Independence. He had reached this conclusion independently, and had planned to publish it in a book which was proscribed even before it could be published. Savarkar commemorated the event in 1907.

Interestingly, writing in the August 28, 1857, edition of the New York Daily Tribune, Karl Marx had stated that the rebellion took on the character of a national revolt against British colonial rule. Marx noted that the British, in creating a native army, had simultaneously organised the 'first general centre of resistance which the Indian people were ever possessed of.'

For the first time, soldiers of the Indian Army, recruited from different communities, Hindus and Muslims, landlords and peasants, had come together in opposition to British rule.

As a part of his effort towards armed revolt against the British, Savarkar got in touch with Gadar Party revolutionaries in north America and along with Madam Cama was active in organising the India Defence League in Europe.

He also got in touch with Irish freedom fighters like Eamon de Valera who were then waging an armed struggle to free Ireland from the British. Savarkar wanted to co-ordinate India's fight for freedom with the Irish revolutionaries.

It was these activities that led to his arrest. En route to India in captivity, he let himself out through a porthole and plunged into the sea. He swam to the shore and sought asylum, but was captured, and against international law, forcibly taken to the British ship.

The year was 1910. Savarkar was tried for treason and sentenced to 50 years. When he landed on the Andaman island, as he trudged up the slope, carrying his baggage on his head, the first thought that entered Savarkar's mind was strategic in nature: One day this Andaman island would be the bastion of free India in the Indian Ocean.

During the First World War, the Germans sent a cruiser Emadem to the Andamans in an unsuccessful attempt to free him. Savarkar firmly believed that an enemy's enemy is a friend and had no hesitation to take German help for Indian freedom.

It is significant that before he escaped from Calcutta to go to Germany, Subhas Bose had met Savarkar in Bombay.

After 14 years of hard labour he was released and kept in detention in Ratnagiri. Savarkar is one of the few leaders of the freedom movement who endured 14 years of hard labour. Restless at the thought of not being able to contribute to the freedom struggle, Savarkar tried every trick to get out of the Andaman jail.

He wrote to the British that he repented his actions. This to Savarkar was a tactic. Although this has been portrayed by his detractors as a 'betrayal,' little realising that Savarkar's intentions were to get out of Andaman alive, by hook or crook.

Savarkar has been vilified as a conspirator and instigator for Gandhi's murder. It is true that the two differed on many issues, but it must not be forgotten that Gandhi himself is on record of having praised Savarkar's efforts in Ratnagiri to fight for Dalit rights.

Savarkar was tooth and nail opposed to Gandhi's insistence on paying Rs 50 crore to Pakistan when Pakistan had invaded Kashmir and the two countries were virtually at war.

But to presume that ideological differences could have lead to personal hatred and conspiracy beats logic. Savarkar was put through hell, and in free India he was a prisoner again.

Judge Atma Charan Agarwal did not find him guilty. Savarkar was acquitted, but the damage had been done, and the image of Savarkar was tarnished.

It is a pity that some of his detractors choose to disbelieve the verdict. Manohar Malgaonkar, after extensive research, published The Men who Killed Gandhi in 1977. He does not point to any guilt on Savarkar's part.

One hopes that the younger generation sees him for what he was and does not view him through a distorted prism. This is the least one could do for someone who devoted his whole life to the Indian freedom struggle, elimination of caste, succour to Dalits, and instilling a strategic culture in India.

© 2025

© 2025