The addition of a million jobs as promised by Tejashwi Yadav would make a big impact.

But the electorate needs to raise its expectations, notes Mahesh Vyas.

Unemployment and employment took centrestage in the Bihar election. Opposition parties used the high unemployment rate as a rallying point in their campaign.

Tejashwi Yadav, the chief ministerial candidate of the united Opposition, raised the bogey of unemployment in Raghopur in mid-October, saying that the unemployment rate in the state was 46.6 per cent.

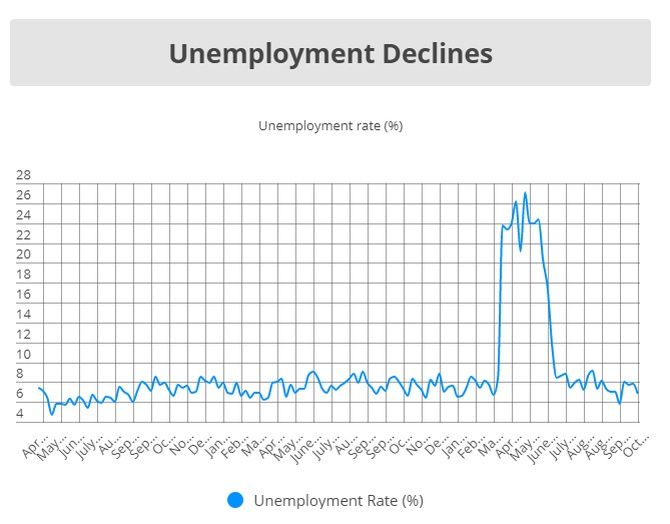

This is a number CMIE put out some time back on Bihar. That was for April 2020, at the peak of the lockdown. The high rate persisted in Bihar at 46 per cent in May as well.

Bihar was among the worst affected states in terms of unemployment during the lockdown.

While the unemployment rate in the state averaged 46 per cent during the peak months, the all-India rate in the same period was 24 per cent.

High unemployment rates in Bihar are surprising because it is relatively a much poorer state and its households, therefore, cannot afford to remain unemployed.

The stringent lockdown must have hurt Bihar households severely. Very high unemployment rate in very poor states is a serious double whammy.

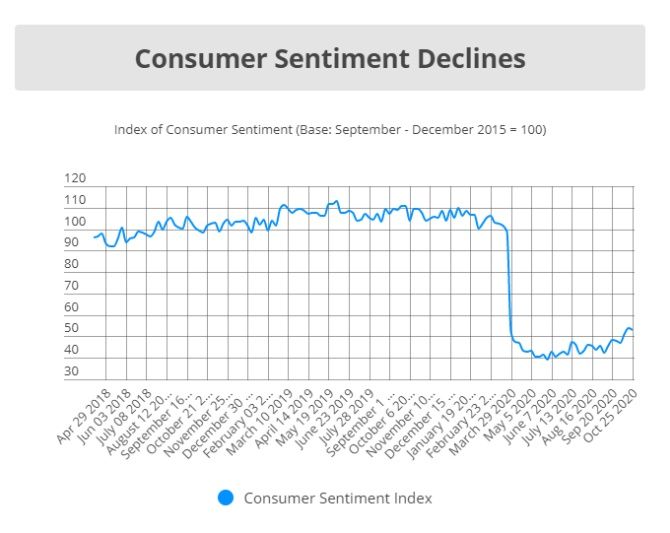

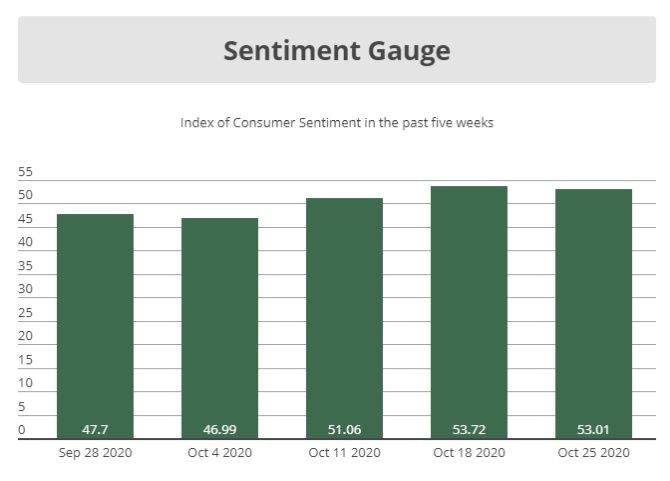

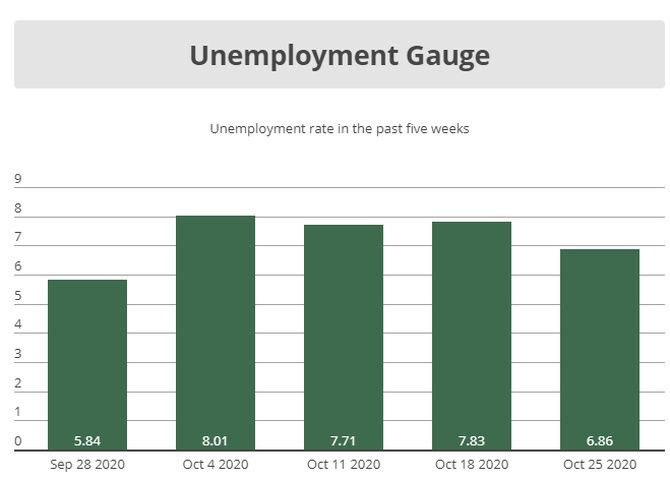

The unemployment rate in Bihar has since come down to 12 per cent. But, even this is much higher than the all-India estimate of 6.7 per cent at the same time.

Unemployment has been rising in Bihar steadily. More importantly, it has been rising at a faster rate than the unemployment rate in India.

The situation seems to have turned for the worse from 2018.

In 2016 and in 2017, the unemployment rate in Bihar was lower than the all-India average. Since 2018, it has been consistently higher. And, the gap between the two has been widening. This could explain the high potency of the unemployment issue in these elections.

Equally effective is the promise of jobs. Yadav announced in mid-October that if his coalition was voted to power, then he would sanction a million jobs in the very first cabinet meeting of the new government.

He stated that there were 450,000 government job vacancies already and that another 550,000 would be needed to bring Bihar on par with all-India numbers. These would be government jobs and permanent in nature.

The clarification on the nature of the jobs, and not just the quantum of a million jobs, is important.

It has evidently electrified the crowds and rankled the establishment.

The unemployment rate is an abstract concept -- per cent of labour force that is looking for jobs and not getting it.

But, by the time you can explain the labour force to the average voter, you've probably lost her.

Nobody feels like it is 12 per cent unemployment rate in Bihar because most don't understand it. It is perhaps easier to feel the abysmally low employment rate.

Only one in three adult Biharis is employed. This is the employment rate. It is more tangible and more importantly, very visible. It was 33.8 per cent in September 2020.

But, in the preceding three months, it averaged only 30 per cent. The national average was 38 per cent in September and 37 per cent in the preceding three months.

Unemployment itself is a misery that in society is often associated with the failure of the unemployed rather than it being seen as a macroeconomic problem that governments need to address.

Politicians highlighting unemployment in society, particularly unemployment of the youth, can be seen to add insult to injury of the unemployed.

The promise of permanent government jobs, on the other hand, is a tangible and appealing proposition.

A million permanent government jobs raises the chances of many aspirants to realise their lifelong dream.

The chief minister derided Yadav's promise of a million jobs saying that there is no money for such jobs.

But the chief minister's ally, the Bharatiya Janata Party, has raised the bar and promised a much higher, 1.9 million jobs if it came back to power although these don't seem to be government jobs. Governments in power have usually been shy of providing jobs.

It is worth wondering why, when there is such a great demand for government jobs and when there is simultaneously a severe shortage of government services, governments continue to stubbornly not provide additional jobs and, therefore, effectively refuse to provide the necessary services that they should.

Governments are unable to provide adequate basic services such as clean water, proper sanitation, primary health and education services, reliable security and timely justice, besides adequate physical infrastructure.

Why have we come to accept bankruptcy of governments as a given to the point where it is allowed to abdicate its basic obligations to society?

Before the lockdown, Bihar provided over 26 million jobs. Non-farm jobs were only 20 million.

The addition of a million jobs as promised by Yadav would make a big impact. But, the electorate needs to raise its expectations from lawmakers.

A one-time bonus of a million jobs or even two million is not adequate. The electorate of Bihar must demand that the employment rate is raised, first to the present all-India average and then to the levels of the better states.

Mahesh Vyas is MD and CEO, CMIE P Ltd.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025