Today as one sees the Owaisi brothers of Hyderabad seeking to lay claim as the custodians of the Muslim vote and the upholders of the community's interests, it is Syed Shahabuddin who springs to mind for having been there, done that, says Saisuresh Sivaswamy.

How does one explain Syed Shahabuddin to a generation for whom the name barely rings a bell, but who in his time not so long ago, was a critical player in the nation's affairs?

And whose role in bringing the nation to its current pass, where identity politics has not only moved from the fringes where it was just a generation ago, when Shahabuddin strode the political proscenium, to the centrestage now?

Would it be accurate to describe Shahabuddin as the originator of Muslim identity politics in free India?

Or should he be described as the mirror image of the nascent Hindu right of the 1980s, who as founder of the journal Muslim India copped many a criticism for not calling it 'Indian Muslim'?

Can Shahabuddin be called the forerunner to the brand of politics practised by the Owaisi brothers of Hyderabad?

It is hard to put Syed Shahabuddin, who gave up his Indian Foreign Service sinecure to dirty his hands with Muslim politics, into any one bin.

To understand him and his politics, it is necessary to go back to the time that made and unmade so many political careers. Including his own.

The 1980s.

Barely a generation had passed since the first general elections had been held in the young Republic. But those years, it seemed, had served to unravel the grand consensus forged in the fire of the freedom movement and which had held the nation-State together so far.

No sooner had the sub-national tendencies in Dravida land been extinguished than the fires leaped out in the north-east.

Even as India was coming to terms with fighting its own citizens, its most prosperous state went up in flames.

It was a splintered, fragmented India that faced the world in the 1980s, one that was at war with itself.

Murphy's law says that what can go wrong will go wrong. It seemed to us then that the perspicacious line had a special resonance for India, for everything went wrong with the country, starting with the election of a political greenhorn as leader with a stupendous majority in those fraught times.

Rajiv Gandhi's heart was in the right place, no doubt about it, though one was not so sure if his head was.

Thus in right earnest he set about putting out the mini fires across India, signing accords swiftly.

One with Laldenga in Mizoram, another with Subhash Ghising in Darjeeling, and the most far-reaching of all, the one with Harcharan Singh Longowal in Punjab that went a long way in restoring dignity to its proud people.

That was the heart in Rajiv working overtime, as he went about correcting the mistakes of the past, most of which can be laid at the door of his redoubtable mother.

But it was the head which was creating a new set of problems.

Even as old fires were extinguished, new ones were being lit, some by commission, some by omission, about which his government had no clue.

The outcome was that the schism between the two major communities of India widened, and has stayed more or less that way for the last 30 years.

Into this breach stepped in Shahabuddin on one side, and the fledgling Bharatiya Janata Party on the other with an incredible Lok Sabha presence of all of 2 members.

The battle in India then was over issues that were prickly as they were unavoidable.

Were they religious in nature, or 'secular'?

What was it when the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the old and abandoned widow Shah Bano's claim for maintenance?

Secular, or religious?

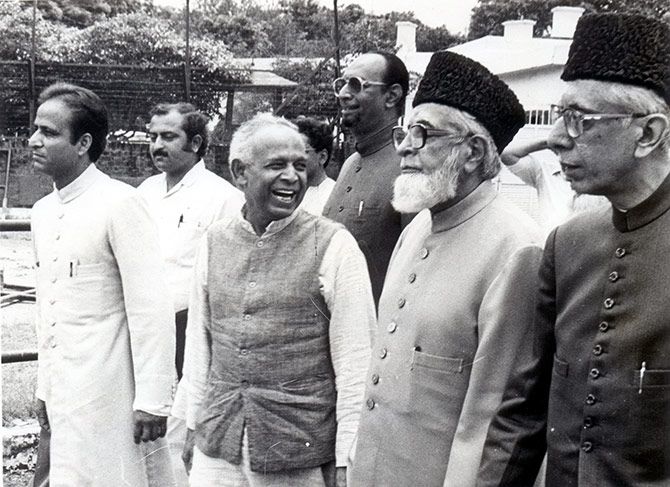

The government of the Westernised, liberal Rajiv Gandhi was expected to respect the court verdict and leave it at that. But he was browbeaten by the vociferous Muslim orthodoxy within his own Congress party, led by the likes of Z A Ansari, and the likes of Shahabuddin outside, to quickly legislate and overturn the court verdict.

That moderate voices like Arif Mohammed Khan's were ignored, their advice disregarded, will always be a black mark against the young prime minister who single-handedly presided over secularism's decline.

It was this single gesture, of succumbing to the orthodoxy, that breathed life into the Hindu Right, represented by the BJP and its aggressive leader, Lal Krishna Advani, even as Shahabuddin grew in stature in his community as one who would fight its battles.

Naturally, when he demanded that Salman Rushdie's novel Satanic Verses be banned, without having read a single word of it, the government quickly obliged, before even our neighbour to the West that was formed to uphold Muslim interests did.

Shahabuddin may have succeeded in articulating his community's position forcefully, but it was the manner of his very intervention that drew the community deeper within itself and further away from the others.

Even conceding the point that he was the tallest Muslim leader in free India -- purely for the sake of argument, mind -- had he chosen a more reasonable path, one of accommodation instead of confrontation, of co-existence instead of conflict, perhaps we will have around us a vastly different India.

If the government had not been herded into cancelling a court verdict, it would have had no reason to open the gates of the Babri Masjid-Ram Janambhoomi to pacify the Hindu Right, a decision whose reverberations can be felt through the decades since.

If the government had not banned Satanic Verses, the Hindu Right's claim of minority appeasement under the Congress would not have assumed the dimensions of Satya Vachan that it did.

Was Shahabuddin really a man of the masses, who held the community in his thrall?

A young editor turned politician from Rajiv Gandhi's coterie certainly did not think so and threw an open challenge to take him on in an electoral battle from his pocket borough of Kishanganj, Bihar.

It was Shahabuddin who turned tail, M J Akbar winning the seat in style on his debut in an election which rejected the Congress otherwise.

And what of Shahabuddin himself? Contesting from Bangalore North as an Independent then, he came 3rd, the seat having been won by C K Jaffer Sharief of the Congress.

So much for epithets like 'tallest Muslim leader' etc that have been used by commentators to describe Shahabuddin these last few days.

The simple fact is that Shahabuddin perfected identity politics way before it became cool and hip. And the simpler fact is that there are no half measures in identity politics, as we are seeing in world capital after world capital where the Right is quickly shuttering things up.

What if Shahabuddin had actually succeeded in emerging as his community's tallest leader? Does the path he had chosen have another exit apart from Jinnahland?

A scary thought, redeemed by India's robust, even if often abused, democracy, which showed the community that its true interests can actually be safer in others' hands.

Today as one sees the Owaisi brothers of Hyderabad seeking to lay claim as the custodians of the Muslim vote and the upholders of the community's interests, it is Shahabuddin who springs to mind for having been there, done that.

There are paths and there are paths through the democratic landscape. The Owaisis are still floundering about, testing their strength and the weakness of their opponents.

Hopefully, they will learn plenty from the late diplomat turned politician's remarkable life to ever be tempted by brinkmanship.

Post-script: Syed Shahabuddin and M J Akbar did finally clash in Kishanganj, in 1991, the former emerging victor, but it doesn't alter what I have written above. Akbar came 3rd, in a year when the Congress put up a better than expected show in most places, and never contested elections after that.

Maybe he will, in 2019. And oh, the person who came 2nd was from the BJP, and was named Kejriwal. Really.

© 2025

© 2025