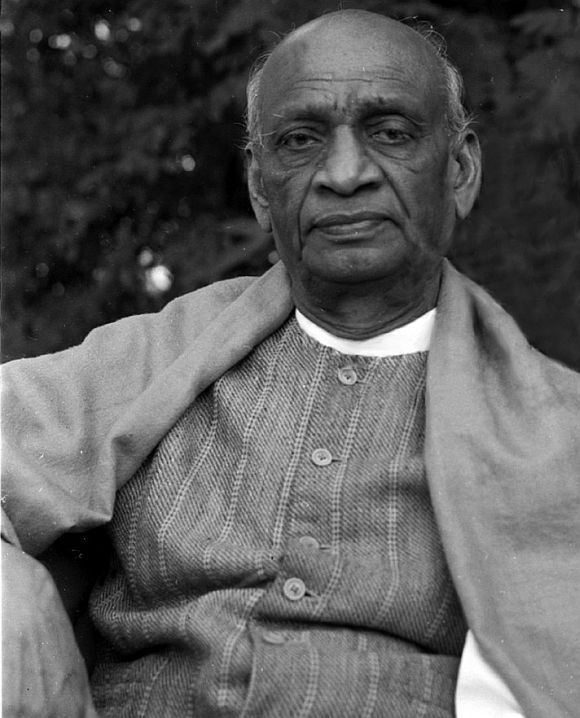

'Sardar Patel's actions must continue to inspire those who have worked for change today and those who aspire to alter the strangling status quo in our national life,' says Dr Anirban Ganguly.

'Sardar Patel's actions must continue to inspire those who have worked for change today and those who aspire to alter the strangling status quo in our national life,' says Dr Anirban Ganguly.

A pensive Dr Rajendra Prasad, writing a little over a decade after India's Independence, noted with great sadness how public memory was 'proverbially short.' This was true, he observed, 'not only regarding facts, events and incidents in which the public are interested but also regarding men who have been in the public eye during their lifetime. I believe this is peculiarly true of India, Indian events and Indian public workers and leaders. Within the last ten years or so how many important leaders have we not already cast into oblivion?'

Ruefully remembering how the great Sardar Patel's memory was itself relegated to the margins of our national political consciousness, Prasad wrote, 'Mahatma Gandhi passed away a little over 11 years ago and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel less than nine years ago. They were both held in highest esteem by a large number of our people -- masses as well as intellectuals. Yet, within this short period we have almost forgotten the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi in many matters and almost completely forgotten Sardar Patel...'

'That there is today an India to think and talk about is very largely due to Sardar Patel's statesmanship and firm administration... yet we are apt to ignore him. No attempt has been made in Delhi to erect a memorial.'

'Let us not run away with the thought,' cautioned President Prasad, 'that his services are any less valuable because we choose not to recognise them.'

One of Vallabhbhai Patel's leading biographers has noted how Jawaharlal Nehru's centenary in 1989, found expression on a thousand billboards, in commemorative television serials, in festivals and on numerous other platforms while Sardar Patel's centenary occurring four months after the Emergency was by contrast, 'wholly neglected by official India and by the rest of the establishment,' allowing a curtain to be drawn 'on the life of one of modern India's most remarkable sons.'

With the call given by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to observe Sardar Patel's birth anniversary as 'National Unity Day' that curtain on Sardar Patel's legacy has begun to be drawn apart and the process of reversing an induced and often deliberate collective amnesia seems to have started.

Such a national gesture and initiation heralds the start of the quest which seeks to rediscover alternate icons and reinstate them in our national consciousness and psyche.

India's civilisational achievements and her ongoing march have never been shaped or directed by a single dynasty or leader -- they have been, instead, the results and manifestations of a collective march, the united quest of generations of thought leaders who have either acted themselves or have inspired others to effectuate a formidable action.

Sardar Patel and his legacy are a flaming and intrinsic part of that unending civilisational march.

From 1917 to 1947 over a period of 30 years, as N V Gadgil noted, 'What Gandhiji conceived, Sardar concretised and carried out,' and still after that his action did not cease.

In the three short years that were given to him, the Sardar worked to concretise the foundations of freedom. His actions, during that crucial phase, must necessarily continue to inspire those who have worked for change today and those who aspire to alter the strangling status quo in our national life -- the gift of a decade of uncertain and procrastinating leadership and governance.

It was the Sardar's decisive and uncompromising leadership, clarity of perception and energy of implementation in times of great national trials and challenges, that perhaps, remains his most enduring and inspiring image.

His daughter and faithful servitor for decades, Maniben Patel, observed how Sardar Patel 'took many unpopular decisions in party and government matters' and yet they were accepted because he had no 'axe to grind' and was not 'amenable to blackmail, he had nothing to lose, had no ambition and no desire to cling to office.'

Sardar Patel's 'vision of free India' perhaps remains as striking and relevant today as it was, when articulated. Speaking in Trivandrum (now Thiruvananthapuram), a few months before his passing, he spelt out vital dimensions of this vision when he said that his ambition was to see 'India going ahead at a uniform pace all throughout the land,' standing 'solidly against all sorts of attacks -- whether internal or external -- and that all needed to unite to harness India's talents and energies in order to remove the miseries of the people.'

For Sardar Patel, the 'poverty of the people' was the first thing that had to be tackled and Maniben Patel recalled how one of the issues that particularly preoccupied him and one which he was particularly keen to address and solve was the precarious food situation in the country.

On the need to set the economy and industrial production on track, Sardar Patel was equally forthright and pragmatic. He told a million strong crowd that had come out to hear him in Kolkata that 'India must produce more in order to exist as an independent country' and that India's 'opportunity of assuming the leadership of Asia will be missed if we cannot set our own economy in order and advance our industries to such an extent as to be able to meet the requirements of deficit countries in Asia.'

Amidst the prevailing chaos and confusion Sardar Patel articulated a grand aim and vision for the people of India.

To the people of India, as G M Nandurkar, one of his sympathetic and therefore perhaps nearly forgotten chronicler, has observed, Sardar Patel was the 'supreme architect of their new born nation. To them he was the sentinel of their frontiers, to them he was the ever vigilant watchman of the law and order in the country, to them he was he was the upholder of their freedom on real democratic lines in terms of equality of citizenship and equalitarian economic order based on the roots and traditions of India,' and therefore they trusted him and responded to his call for nurturing and consolidating unity and freedom.

It was this concern for consolidating unity and freedom that seems to have permeated Sardar Patel's mind even in the last days when he cautioned a colleague in the Cabinet that, 'Whenever in her long history, India has achieved freedom from foreign domination, her independence was menaced not by her external enemies, but by her internal weakness.'

In a moment of quiet yet moving candour, Maniben once wrote, 'It is not for me to interpret and assess the role of my father in the shaping of modern India. Like my father, I leave its judgment to my countrymen and the historians of the future. I must however confess that like millions of my countrymen I feel and feel it so acutely that if the realism and the ideo-practical approach of Sardar would have prevailed on all things concerning the vital interests of India, the picture of India would have been greatly different from what it is today.'

The initiation of Rashtriya Ekta Divas, the call to work for safeguarding national unity and security, and to free India from all her 'internal weaknesses' that had so concerned Sardar Patel, symbolises the beginning of history's true assessment of the man.

That assessment will now at last be greatly and gratefully made.

Dr Anirban Ganguly is Director, Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation, New Delhi.

© 2025

© 2025