'Not even in my wildest dreams did I think I would write a book one day.'

S Dhanuja Kumari's story has all the ingredients you see in a movie. But all the experiences are real.

She grew up in Chengalchoola, a Dalit colony located in the heart of Thiruvananthapuram. Maybe it can be compared to Dharavi of Mumbai, but definitely not of that size. Naturally, her life is shaped by the people she grew up with.

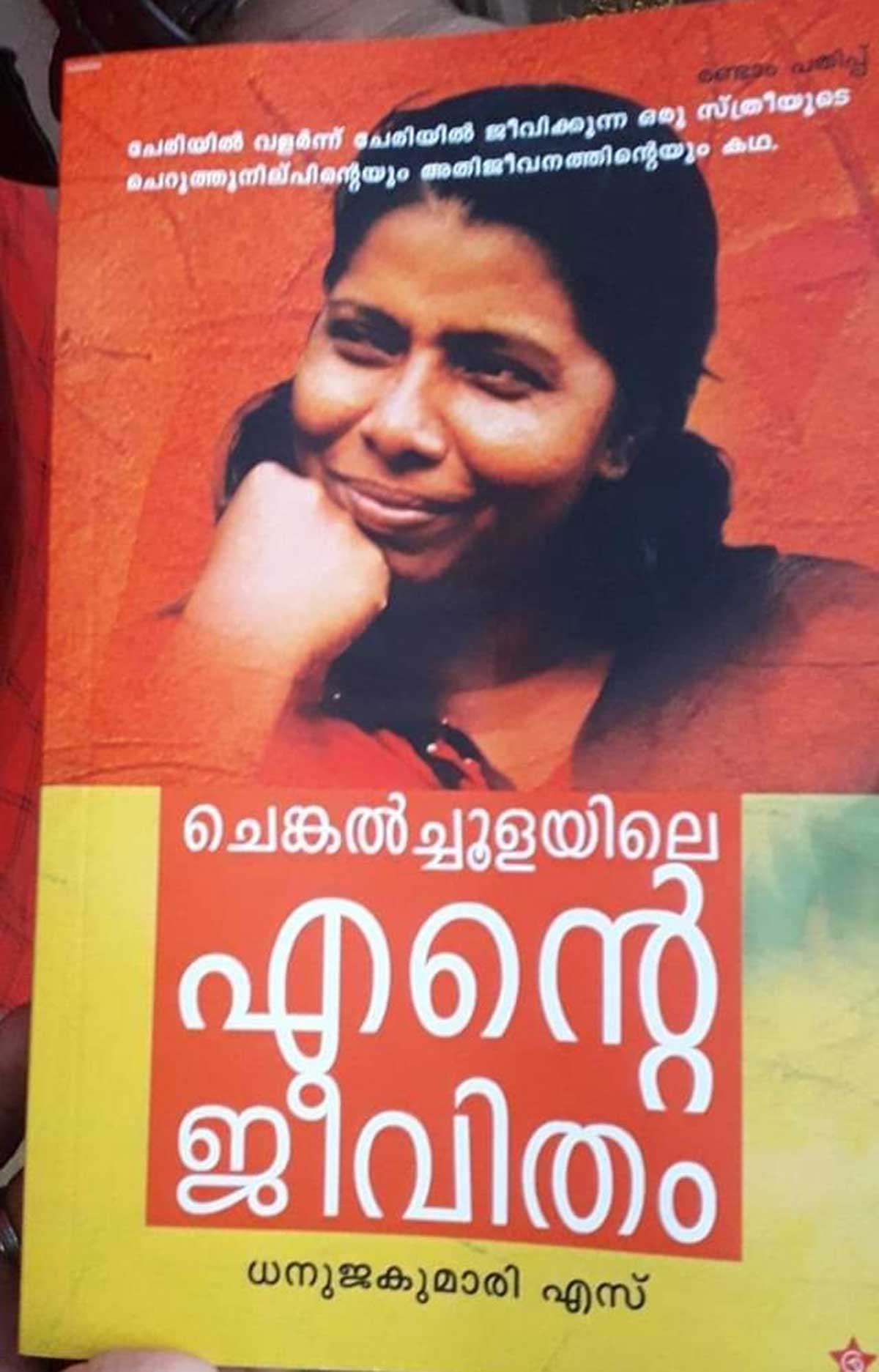

Perhaps, it was by accident that she wrote her autobiography, Chengachoolayile ente Jeevitham (My Life In Chengalchoola). But today, it is the book that defines her identity as a person who showed the world how it was to grw up in Chengalchoola.

Her book has become a landmark not just in her own life but in the lives of all the people who live there.

She has become one of the most about talked persons in Kerala with Kannur University prescribing it as part of the BA curriculum, and Calicut University making it part of its MA curriculum.

That does not mean 49-year-old Dhanuja Kumari has stopped her work as a plastic waste collector as a member of the Haritha Karma Sena.

"I was not aware that my book was part of the curriculum of Kannur and Calicut universities till the editor of my book found out about it," Dhanuja Kumari tells Rediff.com's Shobha Warrier.

A day in the life of Dhanuja Kumari, the plastic waste collector

Though I work for Haritha Karma Sena which is a government project, we from Kudumbashree are involved in the collection of plastic waste from houses. But we are not government employees.

In a way, it is mutually beneficial as we have a job, and the government is able to collect plastic waste from households.

Our income is what we are paid by each house which is around Rs 25,000 a month.

We have to report at our Haritha Karma Sena office at 8 in the morning, but my day starts at 5 in the morning.

As both my sons are married and live separately, we are only three of us -- my husband, my mother and I -- in our house.

My husband Satheesh is a chenda (a percussion instrument) artist, and my mother is also a Haritha Karma Sena worker, like me.

Before the government started the Haritha Karma Sena initiative, we used to collect food waste from households.

As the place I collect plastic waste is around 20 minutes away, I am out of the house with my mother by 6 am.

At 7.50, we have to sign in and after that, we are out to collect plastic from the designated residential area. Since we get information about the area the previous day itself, we inform the Residents Association WhatsApp group of our visit the next day so that they can keep the waste ready to be collected.

My team has three members, and we are designated to collect plastic from 90 houses which is not possible in one day. It takes 2 to 3 days to cover all the 90 houses most of the time.

As we do not have any vehicle, we walk from morning till afternoon collecting plastic from each house. We keep the waste in one area of the residential colony to be segregated alter.

Once in two days or three days, a vehicle from the corporation comes to collect the segregated plastic waste.

By 3 in the afternoon, we are back home.

These days, my evenings are spent at the library we have at Chengalchoola. Those are the most cherished moments of my life.

Starting 'Wings of a Woman', a library in Chengalchoola

During the pandemic when we, the women of Chengalchoola started the library, it was the realisation of a dream I had for many years.

The only luxury I have is read some weekly magazines and newspapers. Not a day passes without me reading the newspaper before getting out of the house to work. That was one habit I can never do away with.

My father who worked as a headload worker, was a member of the CITU (the CPI-M trade union), and he used to bring some weeklies from the party office. Those were the only reading material I had when I was a child. Otherwise, as a child I have not stepped into a library or held a literary work by any renowned author. I would say, I grew up with no contact with books.

That was the kind of childhood I had. And that was the kind of childhood all the children who grow up in Chengalchoola have.

That's why starting a library in our colony was the happiest day of my life.

Writing her thoughts on pieces of newspapers

I used to scribble when something disturbed me, or when something made me very happy.

It was a habit I got from the school I studied. I think I started this habit from when I was in 4th standard.

But there was no discipline in my writing.

We never had a room where we can close the door and write in solitude. I never had any diary. In fact, there was no blank paper at home for me to write anything. So, I used to write on the newspaper pieces which shopkeepers used to wrap provisions.

Though I felt good after writing, after pouring my heart out, I threw them away later.

As a child growing up in Chengalchoola, it was your dream to be a writer, and I never thought I should preserve those pieces of paper which were in fact, a part of me.

Not even in my wildest dreams did I think I would write a book one day.

But it was a dream of mine to start a library in our colony.

Childhood in Chengalchoola

I stopped going to school when I was in 9th standard. And at the age of 15, I got married to the person I fell in love with.

Till around 1990-1991, this was the story of all the girls who grew up in the colony.

There was a reason why we discontinued studies after 7th or 9th. Till 7th standard, all of us went to the school next to our colony where almost all the students were from our colony. So, in a way, as children, we were not exposed to the outside world.

But once we went to other schools as high school students, we realised who we were -- that we were students from the Chengalchoola colony, we were those children with whom nobody wanted to be associated with.

We were those children who were from the lower rungs of society. We were those children who spoke loudly. We were those children who were branded as uncouth and violent. We were those who expressed both happiness and sadness in an exaggerated manner. But then that's us, people of Chengalchoola.

In the new school, we become aware of our skin colour, the way we talk, the language we use, the way we dress... we realise we are different from the rest of the students.

So, in those schools, both the teachers and students looked down on us. We were banished to the last bench even if we were good students.

We were discriminated against as children from the 'colony' with whom the other children should not associate themselves with. We were shunned by both the teachers and students.

I was a good student, and I had this desire to study but the atmosphere in school, the neglect and discrimination I faced there, made me drop out of school when I was in 9th standard.

Today I may feel despondent and angry about what happened to me in school, but when I discontinued my studies, I felt no regrets.

Deciding to live with the person she fell in love with at the age of 15

Most of the youngsters who lived in our colony marry among ourselves. There were not many people who brought someone from outside to our colony after marriage.

I am talking about how it was when I was young. It has changed a lot in the last 35 years.

Like my parents found love, I also found my love in Chengalchoola itself. My mother was just 13 then and she was just 14 when she had me.

Satheesh, my husband, was a dancer in those days. When we got married, I was 15 and he was 20.

At 16, I had my first son and within a year, I had my second son too.

Soon, reality dawned on me that my married life was not what I dreamt about. What affected us was, we got married when both of us were kids and immature, and I became a mother when I was a child myself.

We had two children but no house. My husband used to drink a lot then. I had no clue how to tackle all these problems. I felt the only solution to all my problems was to end my life with my children. I was just 23 then, but I didn't die in my suicide attempt.

The failed attempt made me realise that I had to live and live with dignity.

My life changed after that.

Looking back, I feel I lived because I had to tell people about the life I lead.

If at least one person could change her mind on ending her life after reading my book, I feel blessed.

Discrimination in society made her write her story

Once we decided to make a fresh start, my husband played chenda for 48 hours continuously to enter into the Guinness Book of Records. Though it was unsuccessful, it brought attention on him as a chenda player.

I thought the discrimination I had experienced in school, was a thing of the past. When my sons started studying, I thought the society had changed. I thought people had stopped insulting us using caste names.

But nothing had changed.

Like their father, my children also showed great interest in playing the chenda.

We thought if my eldest son studied at the prestigious Kerala Kalamandalam, and had Kalamandalam as a prefix to his name, his life as an artist would change.

It was not to be. He experienced the worst kind of discrimination and abuse there. His teacher said, as a dalit, he had no right to learn an instrument like the chenda which is mostly played in the temples.

Unable to bear the ill treatment meted out to him by his teacher, my son came back home. When we took him back with a letter from the local MLA, do you know what the teacher said? That even if the prime minister asked him, he would see to it that my son did not study there.

Our dreams were shattered, but it made me angry, really angry.

That was when a journalist who came to study our lives in Chengalchoola encouraged me to write my story.

With the publication of Chengalchoolayile Ente Jeevitham, Dhanuja Kumari becomes an author

Luckily for me, Chintha Publishing House, associated with the Communist party, decided to publish my book.

And I became an author; I who studied only up to 9th standard.

I told the editor of my book not to change my language as it is the language of a person who had not finished school.

I wanted to tell the world that in our colony also, there are people with great talent (pratibha) but outsiders come here in search of only criminals (prathikal). Kerala society only wants prathikal and not pratibha from Chengalchoola.

Today my son has his own music band, and he teaches chenda to children. But I can never forget how society and an institution like Kalamandalam treated a talent like him.

I want this attitude to change. I want society to treat us as human beings.

If I can change the attitude of at least one person towards us through my book, I call myself successful.

Incidentally, I ended my book by saying I dream of having a library in my colony and the dream came true during the pandemic.

Chengalchoolayile ente Jeevitham becomes part of the curriculum in two universities.

I was not aware that my book was part of the curriculum of Kannur and Calicut Universities till the editor of my book found out about it.

It is a great honour that my book is part of the university curriculum and students read it and come to know about a colony called Chengalchoola.

We were discriminated against because we came from Chengalchoola. So, it is like a sweet revenge for me now that the professors will have to say the word Chengalchoola when they teach their students and the students will have to write about Chengalchoola in their exam papers!

But my life changed completely after Malayala Manorama wrote about this last month.

My phone has not stopped ringing after that, and I get at least ten congratulatory calls every day.

There has been no end to felicitation meetings.

Still, I felt there were some people who felt uncomfortable sitting with me on the dais.

There are also many residents where I work as a garbage collector who recognise me now and care to have appreciative words with me.

But I am still the same person, and my routine is also the same. I still get up early in the morning, and start collecting plastic waste from houses.

The only difference is, I attend felicitation meetings in the evenings these days!

The happiness I feel when I attend such functions cannot be expressed in words. I feel as if I am being awarded a Padma Shri or a Padma Bhushan.

Many people ask me why I still work as a garbage collector. I am not ashamed of what I do. Moreover, I am only studied up to 9th standard, and there are limitations to the kind of jobs I can do.

I only want one thing from society, that is to treat us as fellow human beings.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com