'I am here to look after people's needs.'

'I am not bothered about who is a Maoist or who is not.'

Rediff.com's Prasanna D Zore and Uttam Ghosh meet government officials and villagers in Cherpal in the so-called Maoist 'liberated zone' in Chhattisgarh.

- Part 1 in the series: Why did 25 CRPF jawans die in Sukma?

- Part 2: The CRPF is not fighting just the Maoists in Bastar

- Part 3: Hidma Madvi, the Maoist behind the CRPF attacks

- Part 4: Why Adivasis fled their village after the Maoist ambush

With around 400-odd villagers assembled at a clear opening, the site is bustling with Adivasis and government officials.

Not only is it a haat day (a traditional weekly bazaar when villagers, from far and near, gather to buy, sell, and barter goods and necessities of everyday life) it also happens to be the day when the government connects with the people in these far-flung, desolate, Maoist-affected areas to understand their needs and fulfil them on a regular basis.

Most of these villagers come from villages deep inside the jungle and given the state of roads that connected them to the LPG distribution centres in Bijapur, and the expenses involved in travel, not many take the journey to refill the cylinders, they said.

Also called samadhan shivirs (satisfaction conclaves), part of Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Dr Raman Singh's Lok Suraj Abhiyan (programme for people's welfare), a steady stream of government officials mill around with the Adivasis.

"Cherpal was selected because it is one of the least affected villages of all the panchayats from where people have gathered here," says a senior official from the state women and child development department.

Most of them pooled money, rented a tractor, and collectively partook the benefits of the samadhan shivirs.

For administrative convenience, such samadhan shivirs enlist people from a cluster, usually eight or more village panchayats (the basic unit of organisation in rural India), who gather at a common square to partake government services related to health, pre- and post-natal care, distribution of cooking gas cylinders and stoves, hand pumps, land mutation deeds, land plotting records, and caste and residence certificates.

This young boy in Reddi village was oblivious to the problems his village suffered from.

At Cherpal, villagers were supposed to arrive from adjacent panchayats of Santashpur (5.1 km from Cherpal, after hitting proper roads; all other village distances with respect to Cherpal), Doditumnar (27.1 km, with no road connectivity at all), Kamkanar (11 km), Reddi (5.5 km), Mankelli (15 km), Paddeda (2.6 km), and Pedda Korma (no distance available either on maps or with government officials).

Given the distances, poor road connectivity, and more importantly the apathy of the villagers towards the government and the fear of the Maoists, the gathering at Cherpal to participate in the samadhan shivirs is small when one is told that these Adivasis belong to the eight villages mentioned above.

Chandudas D Verma, sub-divisional magistrate, Bijapur, attributes the low turnout of the people to the fear of the Maoists.

"There is always this fear that there could be Maoists in this crowd who keep track of people who attend such government programmes," Verma says, pointing to the people who have assembled under a big pandal.

"That it is a haat day at Cherpal, brings more people here. We arrange such programmes on haat days, so more people come to these shivirs and know about the programmes that the government runs for the welfare of the people," Verma says.

Out of the seven-eight villages that were invited to attend this samadhan shivir, only Cherpal Sarpanch Narsi Hapka, a young cheerful lady in her mid-20s, and Reddi Sarpanch Kanta Vargam, in her late 30s, are in attendance as they interact animatedly with the villagers and the government and health officials about the needs of the villagers.

Unlike government officials, none of the villagers complained about the Maoist 'menace'.

"You may not like it, but not much can happen in these villages without the permission of the Maoists," says the official from the women and child development department.

"For the government this is still part of the Maoists' 'liberated area'," the official adds.

Hapka says she doesn't fear the Maoists, but adds immediately, "the Maoists do not oppose government programmes that solve medical, educational and health related issues of the people."

Kishore Padam, right, and Rut Tati, left, studied in a missionary school in Cherpal.

Narrating his experience of dealing with the Maoists, the health official backs what Hapka says. "They have never troubled me or my co-workers when we go to villages for vaccination and other health and medical outreach programmes," he points out

They usually collect forest produce during the daytime and return to their homes before sunset.

Villagers, the official adds, seeks the Maoists' prior approval before government officials enter areas that fall under the so-called 'liberated zone'.

"This is an unwritten rule, a sort of underhand understanding between the government and the Maoists; but it helps the poor people here who really need it," says a tehsildar at the samadhan shivir in Cherpal.

A number of villagers (village name not published on request) were unhappy with the way the government works.

"I had asked for deepening and beautification of water bodies in our village, but the government response is 'this service is not available for your village'," says Ramesh Ramteke (name changed on request).

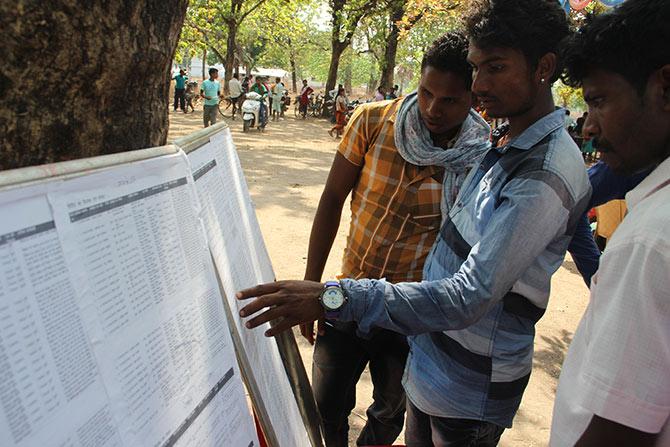

Chandudas D Verma, the sub-divisional magistrate, had placed this board at the entrance to the pandal so that people could check for themselves if their pleas had been fulfilled.

When asked about Ramteke's grievance, Verma, pointing to a small board outside the pandal, says, "Not all services that the villagers ask for can be satisfied by the government."

"We have put up a board there along with the name of the villager, her/his request/demand to the government and the government's response to her/his request on the board there and it is open for everybody to see."

The most popular and crowded section at the Cherpal samadhan shivir is the women and child development department.

The health officials, mid-wives, paramedics and Dr Narendra Kaushik (who was appointed at the primary healthcare centre in Reddi about two months ago) are busy catering to the needs of women who had come with their infants and elderly people.

Dr Kaushik is ably assisted by three nurses/mid-wives trained in para-medicine.

Quite fluent in Hindi, Halbi and Gondi (the languages Adivasis speak in this area), they are quite a help to Dr Kaushik.

Unable to make the mother understand his advice because of the language barrier, Dr Kaushik demonstrates the exercise to her.

The mother, though a little unsure about getting a child to burp by patting his back vigorously, seems relieved.

Dr Kaushik keeps checking the pulse, heartbeat and blood pressure of a steady flow of patients from an open air out-patient department, that is really just a small table and medicines atop it.

A box of condoms can be spotted in a corner on the table, but there seems no takers for it.

"Most of the patients between 30 and 50 come with problems like backache, headache and inflammation whom I administer paracetamol; the lactating and expecting mothers are given folic acid and vitamin supplements," Dr Kaushik tells us.

He was appointed to the Reddi panchayat in March and gets along well with the villagers.

Equipped with instruments and infrastructure that can handle minor surgeries, snake bites, injuries and delivery of babies, Dr Kaushik has become one of the most sought after people in Reddi.

Staying above the healthcare centre in Reddi along with his family (wife and son; his parents had come visiting him from Bilaspur, where he studied medicine), Dr Kaushik is waiting to deliver the first baby there.

She reminds India how neglected and vulnerable children in this conflict zone are.

"Why should I fear anybody?" Dr Kaushik asks, calmly deflecting the question on his and his family's safety while working in a Maoist 'liberated area'.

"I am here to look after people's health needs. The whole village loves me. I am not bothered about who is a Maoist or who is not," he says.

"The government has appointed me to deliver healthcare to the villagers and I am doing my job."

© 2025

© 2025