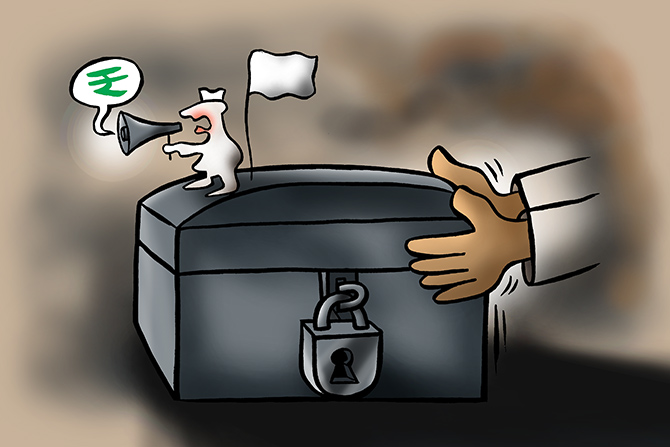

'The anonymous electoral bonds means that political affiliations will be even harder to ascertain for the voter or the minority shareholder.'

'The government of the day will, of course, know, exactly which corporate is making donations to which party.'

'Hence, the government will be in a wonderful position to exert "moral pressure" on corporates which make donations to Opposition parties,' points out Devangshu Datta.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

A recent debate involved a post-modernist interpretation of the meaning of 'only' in the context of what defines a Money Bill in Parliament.

According to the finance minister, 'only' is not open to only one definition.

Another ongoing debate could lead to redefinition of 'transparent' in the context of political funding.

As things stood, political funding was somewhat opaque and difficult to track.

As things will stand in the future, funding patterns will become clearer for the government of the day, while becoming utterly opaque to the common voter.

As of financial year 2016-17, political parties could accept anonymous cash donations up to a limit of Rs 20,000 per donation.

They could accept donations from overseas, after retrospective legislation was pushed through on that front.

Corporates could donate to political parties. But corporate donations had been capped at 7.5 per cent of average net profits for the past three years.

The corporate concerned also had to make a declaration in its statement of accounts, naming the political party (or parties) to which donations were made.

There were several ways to game such rules.

First, a political party could receive a continuous stream of cash handed over by anonymous people donating in sub-multiples up to the cash-limit.

Second, corporates do have a certain leeway to show profits. Many business groups set up multiple companies to juggle profits and losses.

Given corporate taxation (and labour laws to some extent), this is efficient.

The politically-inclined entrepreneur who owned multiple companies could funnel donations by using such dabba entities.

The new rules cut the anonymous cash funding limit to Rs 2,000/donation. But the funding cap on corporates has been removed.

A corporate can donate as much as it likes, without any reference to profits.

Corporates are also no longer required to disclose any political funding -- they don't have to name the recipient party.

A convoluted system of 'electoral bonds' has also been set up. A corporate can buy these bonds and hand the bonds over to the political party of choice.

The reduction in the anonymous cash limit is an eyewash.

There are multitudes of under-employed and unemployed people in the country. If required, they can be gainfully employed, to line up and hand over Rs 2,000 each.

More pragmatically, political parties will just have to print more receipts, so I guess, the printers will be grateful for the extra quantum of business.

Entrepreneurs will heave large sighs of relief. They need to make political donations to run businesses.

The removal of the link to profits means that shell companies can now be set up more easily to make donations.

Those shell companies could even be owned by trusts, or bodies corporate, obscuring the trail further.

Since overseas donations are allowed, the shareholders could perhaps even be obscure entities from Panama, or the Cayman Islands.

The anonymous electoral bonds means that political affiliations will be even harder to ascertain for the voter or the minority shareholder.

The government of the day will, of course, know, exactly which corporate is making donations to which party.

Those bonds are issued against payments received and the government can then reconcile the bond issues against the accounts submitted by political parties receiving the bonds.

Hence, the government will be in a wonderful position to exert 'moral pressure' on corporates which make donations to Opposition parties.

(There is unlikely to ever be a political debate on the definition of moral pressure in this context).

It may be possible for corporates to build up a war chest of electoral bonds, to 'reward' political parties.

For example, a business group may be negotiating for some sops or concessions, or bidding for some major tender or contract.

A shell company could be set up to buy bonds. These bonds could be deployed to 'reward' the political party in power as a quid pro quo.

Variations on such actions could generate fascinating riders and lemmas on the theorems of game theory.

But it is hard to slot this concept into any definition of 'transparency.'

As the Hinglish aphorism goes, 'We are like this only.'

MUST READ features in the RELATED LINKS BELOW...

© 2025

© 2025