| « Back to article | Print this article |

Kargil's first hero

The Kargil War gave India many young heroes who died fighting for a country they loved and swore to protect. To mark the 15th anniversary of the end of the Kargil war, we republish this 2004 feature, saluting Lieutenant Saurabh Kalia, the first martyr.

Someone flicked the television on for the 2 pm news and in spite of her medicine-induced haze Vijay Kalia heard the report correctly from her bedside.

Her son's body had been recovered.

He was just 22 and had joined the Indian Army only four months ago.

She had heard the news in the morning and suffered a mild heart attack. The remedial injection had left her in a stupor.

But now reality stared her in the face.

Two days before New Year 1999 the family was at Amritsar station seeing him off as he boarded the train to join the 4 Jat regiment as a lieutenant. As the train pulled out, he stood by the door, stretching his hand out as if to touch her feet to say goodbye.

That was the last time she saw him.

Fifteen days later, he flew to Leh for his first posting in Kargil, Jammu & Kashmir. Now Lieutenant Saurabh Kalia, who had gone to serve the country, wasn't coming back.

Fifteen days later, he flew to Leh for his first posting in Kargil, Jammu & Kashmir. Now Lieutenant Saurabh Kalia, who had gone to serve the country, wasn't coming back.

It happened five years ago, on June 9, but his mother has not let his memory fall back behind her.

Not even for a moment.

His death brought the Kargil War home to her family in their scenic home in Palampur, Himachal Pradesh -- and to the rest of the country.

Image: Lieutenant Saurabh Kalia's body being carried by army officers at Palampur helipad.

Kargil's first hero

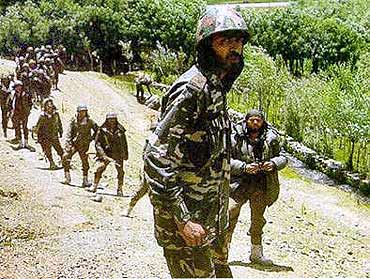

Lt Saurabh Kalia, who was later promoted to captain on the battlefield, was one of the first officers martyred by Pakistani intruders after Pakistan invaded the Kargil region of Jammu and Kashmir in May 1999.

By the time the war ended six weeks later, the Indian Army had evicted the invaders at the cost of 533 brave lives, and earned the maximum number of gallantry awards for battle.

A grateful nation honoured the Kargil warriors with four Param Vir Chakras -- India's highest award for gallantry in battle, nine Mahavir Chakras -- the second highest award for gallantry, 53 Vir Chakras -- the third highest award -- and 106 Sena Medals -- the fourth highest award.

On May 15, Lt Kalia along with five jawans -- Sepoys Arjun Ram, Bhanwar Lal Bagaria, Bhika Ram, Moola Ram and Naresh Singh -- had gone for a routine patrol of the Bajrang Post in the Kaksar sector when their patrol was captured by the enemy.

They were barbarically tortured for 22 days, after which their mutilated bodies were returned to the Indian Army.

Sepoy Arjun Ram was only 18. Lt Kalia, only 22.

Kargil's first hero

Lt Kalia's brother, Vaibhav, now 25, identified his body when it arrived in a coffin wrapped in the national flag in Palampur. Saurabh's face, he recalls, "was the size of my fingers, his eyebrows were the only visible feature, no eyes, no jaw, there were cigarette burns… it was very bad. My parents couldn't have seen him."

Vaibhav pauses, then stops talking.

He does not mention that his brother's eyes and eardrums were pierced, the private organs cut, his chest burned… the details are mentioned in the appeal that his father has sent out to Indian citizens in the last five years.

Their father Dr N K Kalia, a senior scientist at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, has written to every important department in government, to the prime minister, to every embassy and consulate he could find addresses of, to take up the case of human rights violations and the flouting of the Geneva Convention by Pakistan.

Jaswant Singh, then the external affairs minister and a former soldier himself, replied that the matter would be raised with Pakistan at every opportunity.

Kargil's first hero

In Dr Kalia's thick file of letters, there are some written on impressive letterheads after his son's tragic death.

The British high commission -- 'We are seeking from the Indian Army a full report of the postmortem, unfortunately without any success so far.'

Israel -- 'Israel does not have diplomatic relations with Pakistan.'

Germany -- They had contacted the ministry of external affairs and had not received a reply.

"If this had happened to American or Israeli soldiers the culprits would have been hounded around the globe. I received assurances from the government, but in due course the matter got diluted," says Dr Kalia.

Pakistan denied the torture of the six soldiers and rejected India's demand to punish the guilty.

"It was Saurabh's sacrifice that awoke a sleeping nation to the intrusion," says his father, "I will pursue the case with whatever strength I have till I am no more."

Kargil's first hero

On the afternoon of April 30, 1999, Saurabh called home to wish Vaibhav on his 20th birthday.

He would never call again.

'Mama, don't worry if you don't hear from me because I may have to go ahead (to the frontier). I'll call when I get back,' he said.

His last letter home was dated May 10. It arrived on May 24. Dr Kalia walked into the kitchen and told his wife that he had some good news.

She looked up from the vegetables cooking on the stove and said with a smile, 'What good news can it be? My Saurabh's letter must have arrived.'

As they read the letter together, their son was already in captivity and being tortured.

Another young officer Lt Amit Bharadwaj, who led a team looking for Saurabh's patrol party, had also been killed in enemy fire. Amit's body fell off a ridge and was recovered 57 days later.

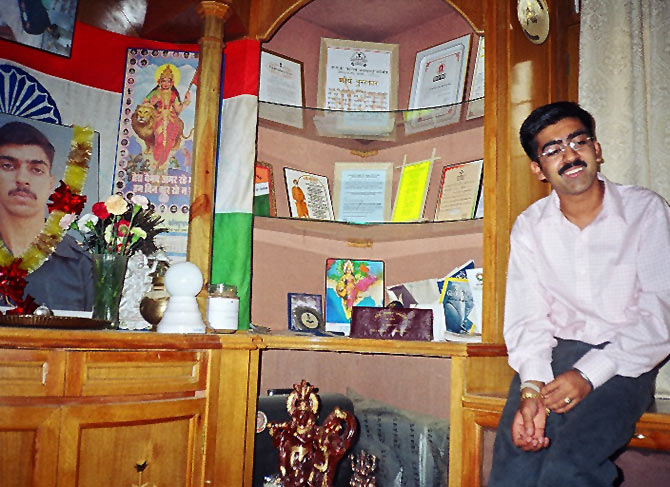

Today, a photograph of Lt Bharadwaj is kept in the one-room museum dedicated to Saurabh in the Kalia home.

Kargil's first hero

When you join the army they take your brains and give you a gun; when you retire, they take back the gun but forget to return the brains.'

That is how Vaibhav teased Saurabh when his brother was a cadet at the Indian Military Academy in Dehradun. But when he picked The Indian Express a few months later, on June 6, 1999, the reality of a soldier's life was no longer a joke.

The report said his brother and his men were missing since May 1. He did not tell his mother, who wasn't feeling too well and had taken the day off from work. 'Rest and don't answer the phone,' he told her as he tucked the newspaper under his arm and rushed to meet his father at his office.

Dr Kalia and he returned home at noon. 'What happened?' Vijay Kalia asked. 'It's about Naughty,' Dr Kalia replied.

At the nursing home in Amritsar where Saurabh was born 22 years earlier, the nurse had called her son a naughty infant. That description became his pet name for the rest of his life.

Kargil's first hero

Is he alright?' Mrs Kalia asked, jumping out of bed. 'Yes,' her husband replied, and gave her the newspaper.

Her son's leave had been sanctioned for May 12, but when he couldn't make it, he had promised his family that he would try and be home for his birthday on June 29.

This couldn't be true, she thought. He couldn't be missing. The army would have informed them if it were so. How could six soldiers disappear without anyone knowing?

The Kalias rushed to the local army cantonment in Holta. There was no news there.

Putting their full belief behind the old saying, 'No news is good news,' they returned home. Vaibhav called The Indian Express office in Chandigarh.

The correspondent told him that a jawan admitted to the local military hospital had narrated the incident.

Desperate for information, they called army headquarters in New Delhi. "They told us Saurabh was missing since May 1," says Mrs Kalia.

"How could that be, we wondered, because we had a letter from him dated May 10."

When then Union minister and Palampur resident Shanta Kumar called Defence Minister George Fernandes, their fears were confirmed.

Saurabh had been missing since May 15.

Kargil's first hero

Lt Saurabh Kalia's body was identified by his commanding officer and flown to Srinagar and then to Delhi where a postmortem was conducted by Red Cross India personnel at the Safdarjung Hospital.

The family was not given the report, says Dr Kalia, because army rules forbade it. It would have helped him pursue his son's inhuman death if he had proof of his torture, he says. He could have attached a copy of the postmortem report and sent it to every national/international forum seeking justice.

The family waited to receive their son at the military helipad, above a verdant green tea estate in Palampur.

When it arrived at noon, about 6,000 people had gathered at the airbase. Senior army officers, state leaders and common citizens paid homage and thousands of people later walked in the funeral procession.

While Vaibhav lit the funeral pyre, his mother held the Indian flag which had draped her son's coffin and Saurabh's cap close to her chest.

Kargil's first hero

There were three Kalias in our course -- Saurabh, Akshay and me,' wrote Lt Himanshu Kalia, 21 Rajput, in his letter of condolence to Dr Kalia, 'Saurabh was the lucky one to have laid down his life for the country.'

Lt Satyesh Yadav, 14 Dogra, his closest friend at the Indian Military Academy, was posted at the China border. His brother sent a letter of sympathy telling the family about their friendship.

A couple in Chennai wanted to know the correct spelling of Saurabh's name, so that they could name their son after the martyr.

An Indian in Japan wrote to say that on the day he was celebrating his birthday, Saurabh was tortured and killed. 'I've decided not to celebrate my birthday for the rest of my life in his honour.'

Lt Col Milkha Singh Grewal, who commanded 4 Jat between 1965 and 1967, wrote that he felt as though his son or grandson has made the supreme sacrifice.

In a room full of memories, there are two rows of shelves full of emotional letters of support from India and abroad. From Sudha Murthy, wife of Infosys Chairman Narayana Murthy in Bangalore, to places as diverse as Nagaland and California.

They are in several languages. There is one in blood.

But none from Jammu and Kashmir, says Dr Kalia.

Kargil's first hero

Eighty thousand e-mails.

Innumerable phone calls.

Letters delivered in sacks from the Palampur post office.

The support was heartening. "The respect and affection that we have received is unprecedented," says Dr Kalia. "There are so many martyrs in this country, but scarcely has anyone received so much."

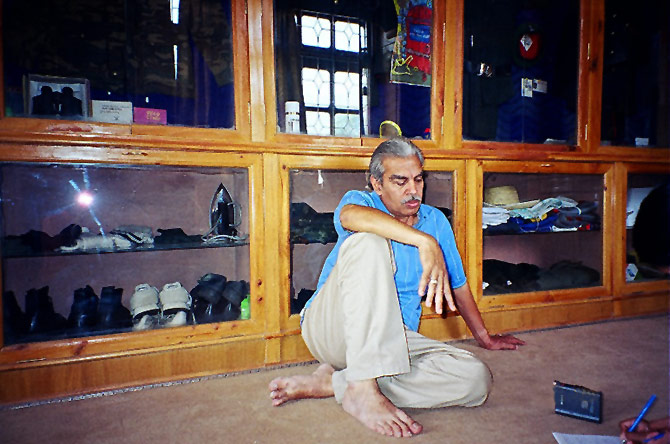

When the second floor of his house was being built, he had a room dedicated to Saurabh and called it The Saurabh Kalia memorial room.

When the second floor of his house was being built, he had a room dedicated to Saurabh and called it The Saurabh Kalia memorial room.

His uniforms, a black tin trunk, the only three photographs of his in uniform, his voter's card, 6 pairs of shoes, a bottle of Chelpark ink, an alarm clock with 'Kalia' written on it, Park Avenue after shave, a poster of Aishwarya Rai from his room at the Indian Military Academy, the wallet recovered from his body…

The room is a temple to a soldier's memory, every article preserved with the care that only parents can bring.

In the centre is a picture of him with his mother. His last at home. She is packing his bags for the Academy while he irons his clothes.

They are both laughing.

The most touching is a cancelled State Bank of India cheque book for his salaried account.

The officer had signed some blank cheques for his mother. Whatever money you need, withdraw it, he had told her.

She never did.

Neither did he, because Lt Kalia's first salary was transferred into his account after he died.

Kargil's first hero

When you are posted in the field area, you can get petty cash for your needs and your salary -- sometimes a consolidated amount -- gets transferred to your account subsequently," explains Vaibhav.

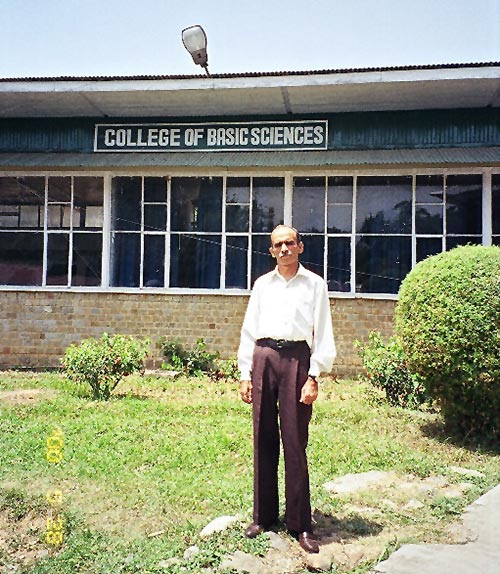

The government gave the family the stipulated compensation, a cooking gas agency and a software engineer's post in the College of Basic Sciences at the Agriculture University in Palampur for Vaibhav.

Saurabh may have wanted to use the money to add to his family's comforts. But his parents thought otherwise.

Saurabh may have wanted to use the money to add to his family's comforts. But his parents thought otherwise.

Their son had done his duty for the country. They were obliged with what the government gave them for his sacrifice but they felt it was not morally right to use Saurabh's money for themselves.

"Saurabh served his country in an unselfish manner," says Dr Kalia, "We didn't want to use it for us."

His parents initiated an annual scholarship in his name at the two schools and the university that he attended. They also donated Rs 15 lakhs to a hospital being constructed, the nurses' hostel of which has been named after Saurabh Kalia.

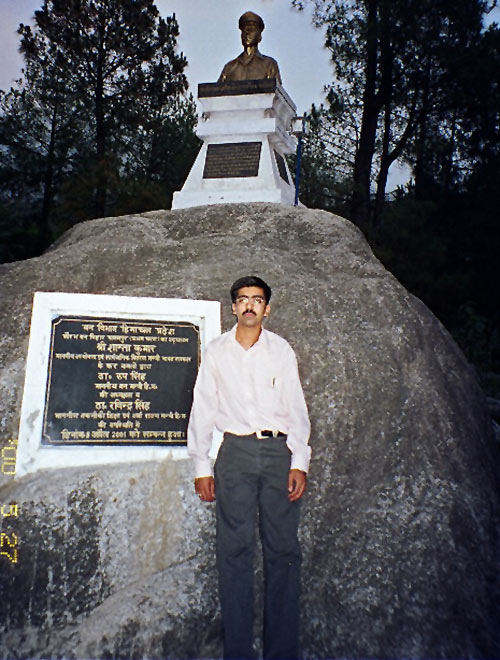

The area where he lived has been renamed Saurabh Nagar and a forest park named Saurabh Van Vihar. His statue was installed there two years ago. On the same rock that was his favourite spot.

Kargil's first hero

In the corridor of the College of Basic Sciences, where Saurabh Kalia studied as an undergraduate hangs a picture of him.

Professor Navneet Kumar Gupta, who taught him zoology, remembers him as a quiet student who never bunked class.

He did not know that Saurabh would join the army one day and make him so proud. "Saurabh was the first," smiles the professor, "after him, 20 of our students joined the armed forces."

Saurabh Kalia himself did not know he would be an infantry officer. He wanted to be a doctor.

A bunch of friends in class had filled the Combined Defence Services form for a lark. They would have to go for the exam to hip-and-happening Chandigarh and have loads of fun.

A day before the exam, the boys boarded a bus to the city. But while the rest of his friends skipped the exam and went for a movie, Saurabh and another boy appeared for the test.

"He told his friends that he would have hell to pay at home if he didn't," laughs Vaibhav.

When the results came, both the friends had passed.

Kargil's first hero

The army's medical panel rejected him twice.

"Once for something called a heart murmur and then for tonsils," recalls Vaibhav.

By the time the ailments were fixed, Saurabh joined the IMA late and had to make up for lost time.

Of course, it was much harder than the daddu chaal (frog skip) that was the punishment for mistakes at the two-hour weekend NCC drill in college.

His pals made Saurabh laugh during the parade, remembers Rajeev Goma, a friend from the NCC course, and the instructor sent him on the daddu chaal around the field on many days.

When he left home, Saurabh's waist measured 34 inches and he loved to sleep.

At the Academy he set the alarm his mother gave him for 4 am.

When he returned to Manali for a camp one-and-a-half months later, his friends could not recognise him. 'They have scraped and chiseled him into shape,' they told Vaibhav on the phone.

Six months on, home for his first break, his waist measured 28 inches.

He liked to eat, travel and dress well, says his mother. "In 22 years, he lived a full life."

A major general told Dr Kalia: ''I've served in the army for longer than how old your son was. Nobody knows me, but your son, they always will.'

Kargil's first hero

Every morning Dr Kalia visits the room dedicated to his son's memory.

His wife does a tikka on Saurabh's forehead in the framed picture kept in front of the Indian flag that had draped his coffin.

The loss is only physical, says his father, "hundreds of thousands of Saurabhs have been taking care of us, we haven't been alone in our grief even for a moment."

Hailing from a family which originally belonged to Lahore, Dr Kalia had seen hard times as a child. He studied hard, completed his PhD, became a scientist and taught his sons the virtues of a principled life.

He accompanied Saurabh for his medical re-examinations to Pune and Delhi. He was there when his son's certificates were lost in a crowded Delhi bus, and was relieved when a good Samaritan posted them back to Palampur.

When he first saw Saurabh in uniform at his passing out parade at the Indian Military Academy, his chest had swelled with pride.

At 22, his first born had become an officer of the Indian Army.

How many middle class fathers had such satisfaction?

Kargil's first hero

I draw my strength from my son. Our suffering can never exceed the physical torture that he went through," Dr Kalia smiles.

His lips curve till the middle of his cheeks, but cannot conceal the pain.

India had always tried to appease Pakistan, he says, and is more interested in being international than national.

"Pakistan's character hasn't changed in 50 years, it will not change ever."

Far from being punished, those responsible for his son's killing have not even been identified yet. Five years later.

Everyone could put this behind and move on, but he can't. He will seek justice at every opportunity, he says, till his last breath.

From a little corner in the beautiful town that was home to his soldier-son, this is the least he can do for a child he lost too soon.

Also see: The soldier who became a legend