|

| Help | |

| You are here: Rediff Home » India » News » Interview » |

| Advertisement | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Advertisement | |||||||||||||||||||||||

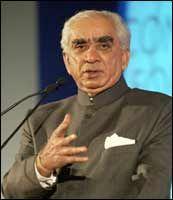

'We needed to make a demon of Jinnah...'

Bharatiya Janata Party leader Jaswant Singh's biography of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, out on Sunday, promises to be much discussed. He talks about it to Karan Thapar on the CNN-IBN channel's 'Devil's Advocate' programme. Excerpts:

Bharatiya Janata Party leader Jaswant Singh's biography of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, out on Sunday, promises to be much discussed. He talks about it to Karan Thapar on the CNN-IBN channel's 'Devil's Advocate' programme. Excerpts:

Mr Jaswant Singh, let's start by establishing how you as the author view Mohammed Ali Jinnah. You don't subscribe to the popular demonisation of the man?

Of course, I don't. If I wasn't drawn to the personality, I wouldn't have written the book. It's an intricate, complex personality of great character, determination...

And it's a personality that you found quite attractive?

Naturally, otherwise, I wouldn't have ventured down the book. I found the personality sufficiently attractive to go and research it for five years.

Jinnah joined the Congress party long before he joined the Muslim League and in fact when he joined the Muslim League, he issued a statement to say that this in no way implies "even the shadow of disloyalty to the national cause". Would you say that in the 20s and 30s, and may be even the early years of the 40s, Jinnah was a nationalist?

The acme of his nationalistic achievement was the 1916 Lucknow [Images] Pact of Hindu-Muslim unity and that's why Gopal Krishna Gokhale called him the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.

Many people believe Jinnah hated Hindus?

Totally wrong! His principal disagreement was with the Congress party. He says this even in his last statements to the press and to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan. He had no problems whatsoever with the Hindus.

As you look back on Jinnah's life, would you say that he was a great man?

Yes, because he created something out of nothing and single-handedly, he stood up against the might of the Congress party and against the British, who didn't really like him. He was a self-made man. He carved out in Bombay a position in that cosmopolitan city being what he was, poor. He was so poor, he had to walk to work.

How seriously has India misunderstood Jinnah?

I think we misunderstood because we needed to create a demon.

We needed a demon because in the 20th century, the most telling event in the entire subcontinent was the partition of the country.

Your book reveals how people like Gandhi, Rajagopalachari and Azad could understand the Jinnah or the Muslim fear of Congress majoritarianism but Nehru simply couldn't understand. Was Nehru insensitive to this?

No, he wasn't. Jawaharlal Nehru was a deeply sensitive man.

But why couldn't he understand?

He was deeply influenced by Western and European socialist thought of those days. Nehru believed in a highly centralised polity. That's what he wanted India to be. Jinnah wanted a federal polity.

Because that would give Muslims the space?

That even Gandhi understood.

You conclude that if Congress could have accepted a decentralised federal India, then a united India, as you put it, "was clearly ours to attain". Do you see Nehru at least as responsible for partition as Jinnah?

He says it himself. He recognised it and his correspondence, for example with the late Nawab Sahab of Bhopal, his official biographer and others. His letters to the late Nawab Sahab of Bhopal are very moving.

When Indians say Jinnah was the villain of Partition, your answer is there were many people responsible and to single out Jinnah, as the only person or the principal person, is both factually wrong and unfair?

It is. It is not borne out of events. Go to the last All India Congress Committee meeting in Delhi [Images] in June of 1947 to discuss and accept the (partition) resolution, Nehru-Patel's resolution. Ram Manohar Lohia had moved the amendment. It was a very moving intervention by Ram Manohar Lohia and then Gandhi finally said, we must accept this partition.

Partition is a very painful event. It is very easy to assign blame but very difficult thereafter. Because all events that we are judging are ex post facto.

So, Pakistan was in fact a way of finding, as you call it, 'space' for Muslims?

He (Jinnah) wanted space in the Central legislature and in the provinces, and protection of the minorities, so that the Muslims could have a say in their own political, economic and social destiny.

And that was his primary concern, not dividing India or breaking up the country?

No. He in fact went to the extent of saying, let there be a Pakistan within India.

In other words, Pakistan was often 'code' for space for Muslims?

That's right. I find that it was a negotiating tactic, because he wanted certain provinces to be with the Muslim League. He wanted a certain percentage (of seats) in the Central legislature. If he had that, there would not have been a partition.

Your book shows how repeatedly people like Rajagopalachari, Gandhi and Azad were understanding of the Jinnah need or the Muslim need for space. Nehru wasn't. Nehru had a European-inherited centralised vision of how India should be run. And a highly centralised India denied the space Jinnah wanted?

A highly centralised India meant that the dominant party was the Congress party. He (Nehru) in fact said there are only two powers in India -- the Congress party and the British.

So, this majoritarianism of Nehru actually left no room for Jinnah?

It became a contest between excessive majoritarianism, exaggerated minoritism and giving the referee's whistle to the British.

Your book raises disturbing questions about the partition of India. You say it was done in a way "that multiplied our problems without solving any communal issue". Then you ask "if the communal, the principal issue, remains in an even more exacerbated form than before, then why did we divide at all?"

Yes, indeed, why? Look into the eyes of the Muslims who live in India and if you truly see through the pain they live -- to which land do they belong? We treat them as aliens, somewhere inside, because we continue to ask, even after Partition you still want something? These are citizens of India -- it was Jinnah's failure because he never advised Muslims who stayed back.

One of the most moving passages of your biography is when you write of Indian Muslims who stayed on in India and didn't go to Pakistan. You say they are "abandoned", you say they are "bereft of a sense of kinship", not "one with the entirety" and then you add that "this robs them of the essence of psychological security".

That is right, it does.

Your book also suggests you believe India could face more Partitions. You write: "In India, having once accepted this principle of reservation, then of Partition, how can we now deny it to others, even such Muslims as have had to or chosen to live in India?"

The problem started with the 1906 reservation. What does the Sachar committee report say? Reserve for the Muslim. What are we doing now? Reserve. I think this reservation for Muslims is a disastrous path. I have myself, personally, in Parliament heard a member subscribing to Islam saying we could have a third Partition, too. These are the pains that trouble me. What have we solved?

You are being honest enough to point out that this intellectual contradiction lies today at the very heart of our predicament as a nation.

It is. Unless we find an answer, we won't find an answer to India-Pakistan-Bangladesh relations.

Are you worried that a biography of Jinnah, that turns on its head the received demonisation of the man; where you concede that for a large part he was a nationalist with admirable qualities, could bring down on your head a storm of protest?

I have written what I have researched and believed in. I have not written to please - it's a journey that I have undertaken, as I explained myself, along with Mohd Ali Jinnah -- from his being an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity to the Qaid-e-Azam of Pakistan

In 2005, when L K Advani [Images] called Jinnah's August 11, 1947 speech secular, he was forced to resign the Presidentship of the party.

This is not a party document, and my party knows I have been working on this. They might disagree, that's a different matter. Why should there be anger about disagreement? Let a self-sufficient majority, 60 years down the line of Independence, be able to stand up to what actually happened pre-47 and in 1947.

Let me raise two issues that could be a problem for you. First, your sympathetic understanding of Muslims left behind in India. You say they are abandoned, they are bereft, they suffer from psychological insecurity. That's not normally a position leaders of the BJP take.

The BJP is misunderstood also in its attitude towards the minorities. Every Muslim that lives in India is a loyal Indian and we must treat them as so.

But you are the first person from the BJP I have ever heard say, "Look into the eyes of Indian Muslims and see the pain." No one has ever spoken in such sensitive terms about them before.

I am born in a district; that is my home -- we adjoin Sind, it was not part of British India. We have lived with Muslims and Islam for centuries. They are part. In fact in Jaisalmer, Muslims don't eat cow and the Rajputs don't eat pig.

I am cautioning India, Indian leadership. I have said that I am not going to be a politician all my life, or even a Member of Parliament. But I do say this -- we should learn from what we did wrong, or didn't do right, so that we don't repeat the mistakes.

| © 2009 Rediff.com India Limited. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer | Feedback |