|

|

| Help | |

| You are here: Rediff Home » India » News » Special |

|

Salman Rushdie | ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

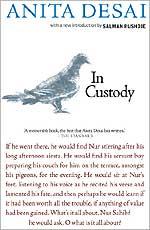

Being named a fellow of the Sahitya Akademi is a rare honour. When Anita Desai joined this elite group on November 30, Random House India celebrated the event by re-releasing three of her novels, with new covers, and new introductions by eminent writers.

Salman Rushdie has written the new introduction to In Custody, which was later made into a film by Ismail Merchant, starring Shashi Kapoor and Om Puri [Images].

In the introduction, Rushdie talks of how In Custody reveals a new facet to Anita Desai, the writer. He also talks of her undeniable place in the world of literature.

Anita Desai is by now firmly established as the pre-eminent Indian novelist of her generation, and the writing mirrors the woman to a quite remarkable degree. When you first encounter it, the prose seems to whisper, to speak so softly as to risk going unheard, but as you bend your ear to listen, you hear many unexpected notes of wicked comedy, of sharp, even biting perceptions about her fellow men and women, and of a clear-sighted unsentimentality about human nature that is anything but frail. The voice takes hold of the reader, gently, irresistibly, and its strength and clarity soon come to seem like small miracles.

In an age when writers are often clumsily grouped together by ethnic origin, or language, or corralled into the ghettoes of ideology and gender, it is easy to forget the trans-national, trans-lingual, and indeed trans-sexual nature of all great literature, in whose frontierless landscape R K Narayan's Malgudi is in the same neighbourhood as William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County and Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Macondo, closer to those places, indeed, than to any place in India; and thanks to the translations commissioned by the Argentine publisher Victoria Ocampo, a generation of Latin American writers was reared on the works of Rabindranath Tagore.

When I think of Anita Desai, I see her most clearly as a figure standing, as an equal, beside Jane Austen, that other great Indian novelist, creator of brave, brilliant women trapped by conservative social mores into becoming mere husband-hunters, women who would be very recognizable to denizens of, for example, the Delhi of Clear Light of Day. And because, while she is wholly Indian, she is also half-European, I think of her in the company of other insider-outsiders such as the white Caribbean novelist Jean Rhys, author of Wide Sargasso Sea, or the half-Sikh, half-Hungarian painter Amrita Sher-Gil. Nor should Anita Desai be placed in exclusively female company. As In Custody makes plain, she has cared as much about, and been shaped as deeply by, the great (male) Urdu poets as by any woman's poems.

Until the publication of In Custody, one might have said that the subject of Anita Desai's fiction was solitude. Her most memorable early creations -- the old woman, Nanda Kaul, in Fire On The Mountain (a novel to which her daughter Kiran's The Inheritance of Loss owes an immense artistic debt), or Bim in Clear Light Of Day -- were isolated, singular figures. Those books themselves felt like private universes, illuminated by their author's perceptiveness, delicacy of language and sharp wit, but remaining, in a sense, as solitary, as separate, as their characters.

Until the publication of In Custody, one might have said that the subject of Anita Desai's fiction was solitude. Her most memorable early creations -- the old woman, Nanda Kaul, in Fire On The Mountain (a novel to which her daughter Kiran's The Inheritance of Loss owes an immense artistic debt), or Bim in Clear Light Of Day -- were isolated, singular figures. Those books themselves felt like private universes, illuminated by their author's perceptiveness, delicacy of language and sharp wit, but remaining, in a sense, as solitary, as separate, as their characters.

In Custody was, therefore, a novel of transformation for its author, a doubly remarkable piece of work because, in this magnificent book, Anita Desai chose to write not of solitude but of friendship, of the perils and responsibilities of joining oneself to others rather than holding oneself apart. And, at the same time, she wrote, for the first time, a very public fiction, shedding the reserve of the earlier books to take on such sensitive themes as the unease of minority communities in modern India, the new imperialism of the Hindi language, and the decay that, now even more than when the book was written, was and is all too tragically evident throughout the fissuring body of Indian society. The courage of the novel is considerable, and so is its prescience. The slow death of my mother tongue, Urdu, is much further advanced than it was 23 years ago, and much that was beautiful in the culture of Old Delhi has slipped away for ever.

The story contrasts the slow death of a false friendship and the painful birth of a true one. Deven, a lover of Urdu poetry who has been obliged to teach Hindi in a small-town college for financial reasons, is bullied by his boyhood chum Muras to go to Delhi and interview the great, ageing Urdu poet Nur Shahjehanabadi for Murad's rather ridiculous magazine. The relationship between the weak, unworldly Deven and the posturing bully Murad seems at first like something out of Narayan. But Narayan's meek characters usually stand for traditional India, while his bullies represent some aspect of the modern world. In Custody has no such allegorical intentions. Murad's appalling behaviour -- he all but ruins Deven while appearing to help, wasting money on a poor tape recorder for the interview, then arranging for an incompetent 'assistant' who completely fouls up the recording, and finally refusing to settle the bills arising from the event -- makes the fine, unsentimental point that our friends are as likely to destroy us as our enemies.

In the film Ismail Merchant made of In Custody, probably his finest effort as a director, the roles of Nur the poet and Deven the acolyte are sensitively played by two great actors, Shashi Kapoor and Om Puri. And yet, the film's casting does in part undermine the novel's vision. Nur's body 'had the density, the compactness of stone. It was large and heavy not on account of obesity or weight, but on account of age and experience,' Anita Desai writes. This was not exactly true of his movie incarnation, Shashi Kapoor, but the beauty of Kapoor's spoken Urdu did much to make up for the physical differences. The biggest problem in the film is that the age gap between Kapoor and Puri is not wide enough. The novel contrasts youth and experience; the film sets greatness against greenness, but by narrowing the generation gap it loses a dimension.

And the novel's emotional heart lies in this relationship. At first the young teacher's dream of the literary giant appears to have come true. Then, superbly, we are shown the great man's feet of clay: Nur beset by pigeons and by other, human, hangers-on; Nur gluttonous, Nur drunk, Nur vomiting on the floor. Here allegory perhaps is intended. 'How can there be Urdu poetry,' the poet asks rhetorically, 'when there is no Urdu language left?' And his decrepitude -- like the derelict condition of the once-grand ancestral home of Deven's fellow-lecturer, the Muslim Siddiqui -- is a figure of the decline of the language and culture for which he stands. The poet's very name, Nur, is ironic. His is a 'light' grown very dim indeed.

Once again, however, the point being made is not allegorical. The beauty of In Custody is that what seems to be a story of inevitable tragedies -- the tragicomedy of Deven's attempt to get his interview being the counterpoint to the more sombre tragedy of Nur's slide towards oblivion -- turns out to be a tale of triumph over these tragedies. At the very end, Deven, beset by crises, hounded by Nur's demands for money (for a cataract operation, for a pilgrimage to Mecca), understands that he has become the 'custodian' both of Nur's friendship and of his poetry,

and that meant he was the custodian of Nur's

very soul and spirit. It was a great distinction.

He could not deny or abandon that under any

pressure.

Once Deven has understood this, the calamities of his life seem suddenly unimportant. 'He would run to meet them,' and he does.

The high exaltation of such a conclusion is saved from becoming merely lush by Anita Desai's wholly admirable dryness of manner. Her vision is unsparing. Urdu may be dying, and her novel may in part be a lament for that death, but nevertheless in the character of Siddiqui she shows us the worst side of Urdu/ Muslim culture -- its snobbishness, its eternal nostalgia for the lost glory of an early Empire. And, most significantly, we see while Deven may be willing to embrace his responsibilities to Nur, he utterly fails to do likewise with Nur's wife or his own. He feels too threatened by the former even to read her poetry, and is too careless of his own poor Sarla with her faded dreams of 'fan, phone, frigidaire' to build any sort of real relationship with her at all.

That Anita Desai has so brilliantly portrayed the world of male friendship in order to demonstrate how this, too, is a part of the process by which women are excluded from power over their own lives is a final, bitter irony behind what is an anguished, but not at all a bitter book.

Excerpted from In Custody by Anita Desai, with permission from the publishers, Random House India, Rs 295.

DON'T MISS

Salute Anita Desai

YOUR SAY!

Have a question for Anita Desai? | Met her?

Want to buy Anita Desai's books?

Rediff Specials

|

|

| © 2007 Rediff.com India Limited. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer | Feedback |