Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/A Ganesh Nadar in Ramnad

October 22, 2004

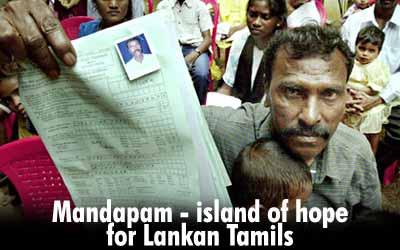

Mandapam means 'hall' in Tamil. This place is a hall where refugees congregate. Some are allowed to stay, the rest are transferred to other districts in Tamil Nadu.

The refugee camp in Mandapam was built to accommodate Indian Tamils fleeing Sri Lanka after the island regained independence.

As long as the British were ruling Ceylon, as it was then called, they ensured that there were no inter-community clashes. But after Independence there was no such restraining factor and the Sri Lankan Tamils forced the Indian Tamils out. That was when Mandapam first came into focus.

The refugee camp, which was lying unused for many years thereafter, again came into prominence in 1983 when the ethnic war erupted in Sri Lanka. This time it was the Lankan Tamils who were being hounded by the Sinhalese.

Two years ago a Norwegian-backed ceasefire was declared. The calm, however precarious, defied all odds and slowly started attracting the attention of the displaced Tamils. The Mandapam camp inmates have been thronging the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees since then.

The procedure a prospective traveller has to go through is this: the high commissioner checks the applicant's antecedents, including whether s/he is a suspected militant, and okays the petition. The collector of Ramnad district then interviews the refugee and gives his consent. After this, the Indian government provides the refugee an air ticket and Rs 500 for expenses. When the person reaches Colombo, the Sri Lankan government contributes another Rs 5,000 towards rehabilitation.

The Rs 5,000 is just enough to get you home, says Raman (name changed), a refugee in the Mandapam camp. "My home is 500 km away from Colombo. We have to hire a van to go home. We cannot wait at a bus stop because the Sinhalese hate the sight of us. Furthermore, because we are returning by air from India, they presume that we are rich and carrying a lot of money or gold. They won't hesitate to slit our throats to steal our belongings."

The constant fear of being robbed is one of the reasons that in spite of all the free allowances, refugees prefer to go back as they came -- illegally, by sea. By sea the refugees land at Talaimannar, part of the Tamil heartland, and not Colombo, which is predominantly Sinhalese.

Adding to the refugees' woes is police harassment.

The Tamil Nadu police, which rounded them up when they came into India, now wants a fee to let them go back, according to another refugee, Kannan. He says the police have nothing against repatriation; they are, in fact, happy to be rid of them. It is their goods that they are interested in. "The fishermen who smuggle you out charge Rs 5,000 to get you across just 18km of sea," says Kannan. The Lankan Tamils, therefore, always carry bidis, cigarettes, diesel, and anything else that can be pawned for some cash, he says.

The cops in turn accuse the refugees of trafficking in heroin.

"A few bad eggs have given our entire community a bad name," laments Raman. "We are looked after by the Indians and we pay them back by smuggling out heroin!"

But only one in 10 refugees going back by sea is arrested.

Controlling the sea routes is a near impossible task as there are innumerable fishing boats out in the waters at all hours. Also, checking each boat is impossible, admit police.

Smuggling of refugees is ebbing now, mainly because of the heightened activity in Lankan waters.

The Sri Lankan navy and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam's Sea Tigers are at loggerheads, making the zone risky for the small fishing boats ferrying refugees.

Back in the Indian camps, the head of a family of refugees gets Rs 100 every fortnight, the woman gets Rs 75, and other members get Rs 60 each. Rice is supplied for Re 0.55 a kilo. The rations are low, leading many to seek work outside. Many Indians employ the labourers in fields and on construction sites. The Lankans get paid on par with their Indian counterparts and there is no exploitation.

"It is peaceful here, I love this country and its people. But I have lost my youth. In my prime I was a refugee. We lost everything when we were chased out of our homes. You think it is easy to rebuild our lives after we go back?" one refugee asks.

"There we will have to pay 20 per cent of our earnings to the LTTE. I don't mind paying; many of our members have lost their limbs fighting for the Tamil cause. The LTTE is feared, but they are disciplined. You will never find a LTTE member teasing a woman or misbehaving with her. If anybody does so, he is tied to a tree and shot, however high he may be in the LTTE hierarchy. They never rob people. They only ask for tax."

The statement echoes the feelings of most refugees camping in Mandapam. There have been suggestions that the Indian government should start a one-way boat service to the Tamil Northeastern province in Lanka.

That is a suggestion the Indian government would do well to take note of; especially if it wants to ease Mandapam's historic burden and its own...

Photograph: DIBYANGSHU SARKAR/AFP/Getty Images | Headline Design: Uday Kuckian