Home > News > Diary

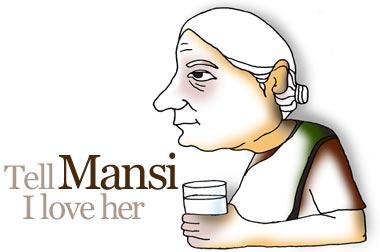

Mansi Bhatia

Dadi was the epitome of resilience, compassion, patience and devotion. Not once have I seen her lose her composure. Not when she was wheeled into the intensive care unit. Not when doctors gave up on her. Not even when Dada, my stone-faced grandfather, broke down the night she lay still in coma.

Dadi and I shared a special bond. I was her oldest grandchild, the one to first give her the stature of a grandmother. Still, she set the strictest standards for me.

I remember her overworked hands holding my glass of milk every evening at six. I would make faces, feign stomachache, sometimes simply ignore her. Her wrinkled face would remain resolute and emotionless. She would hear no arguments and never presented one of her own. A while later she would plod back to the kitchen with an empty glass and a glorious smile.

It was fun to watch her work in the kitchen with my mom. Dadi rewashed everything Mumma had cleaned minutes ago. She rearranged all the containers and hid all electronic gadgets in the cupboards.

She hovered over Mumma's head, quietly supervising and critically observing. She brooked no interference. In her two-month stay at our house every year, the maids refused to come.

Dadi also cooked onion-free versions of the same dish Mumma prepared for dinner. Dad had been raised to despise onions and garlic, while for mom these two were an integral part of every dish. It was so comical to see him gulp down both versions in an effort to keep the two women in his life happy.

At nights Dadi would place my head on her lap and tirelessly relate stories about her childhood. How she, her three sisters and four brothers climbed mango trees, played for hours on end, did household chores and spent evenings in the temple. She taught me chants to recite when facing the idols of her revered gods, painstakingly going over the mantras, explaining what each verse meant, and which evil spirit it fended off.

Much as I relished her tales of yore, I detested sitting in her prayer room with folded hands. Dadi, on the other hand, beamed with pride every evening as I recited the prayers before mute temple idols and a bored priest. She knew I would concede to everything she asked of me -- I was her little pet. It was difficult to refuse to walk her down to the market; she would always succeed in coercing me to visit her relatives, or watch mythical soaps on TV.

And to be honest, I liked indulging her.

Her mornings started even before the sun had a chance to rise. She would make her bed, bathe, clean the kitchen, and slowly climb the staircase to the terrace to pray. Even when she developed arthritis, Dadi continued to follow this daily ritual.

With her bent back facing the west, she kept murmuring until the birds' chirping fused with her own muted prayers. Nothing and no one could stop her from cleaning the house, making everyone's beds, washing the dishes and clothes, and fetching groceries. She felt it was her right to take care of everything and everyone. And no doctor could dictate to her what she could or could not do.

It was on one such chilly morning in Mathura, where Dadi stayed for the rest of the 10 months, that she passed out while washing clothes. Dada rushed her to the nearest hospital immediately. She was diagnosed with severe jaundice.

My father took the first train available and was by her side in 28 hours. The disease had gone undiagnosed for a week and she had been exerting herself routinely when she should have been in bed, resting. Her two sons and three daughters decided to shift her to a bigger hospital. This time Dadi did not resist.

She kept chanting her mantras believing -- knowing -- her Gods would not fail her.

Two days later the telephone rang at midnight. Dadi was repeatedly calling out my name. The doctors did not know when she would breathe her last. Mumma and I found ourselves in the train in the next four hours.

By the time we reached the hospital, Dadi had slipped into coma. Lying on the bed with numerous pipes invading her bloated body, she was unrecognisable. Gone was that shine in her eyes, the crooked wrinkled smile, the affectionate nod of the head.

Up to the previous night she had been calling my name. They kept telling her I would come. She kept telling them it would be too late. The last words she had said to my granddad were, "Tell Mansi I love her."

Sitting by her bedside, holding those crumpled lifeless hands, I found myself chanting the Gayatri Mantra. I chanted everything she ever taught me to ward off evil spirits. I had been to all the 14 temples she visited every day. I had knelt and prayed with all my heart for her life. All I wanted was for Dadi to open her eyes and look at me, but her face remained emotionless and resolute.

Two days later she died. Just as silently as she had gone about her day-to-day chores, Dadi left us.

It has taken seven long years for me to pen this down in her memory. It's about time, I guess.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh