Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/M D Riti

August 19, 2003

A major astronomical discovery has a certain value that is not measurable like, say, an Infosys stock option," says Dr Srinivas Kulkarni. "Who can predict when an Indian might make such a discovery and make India proud of him or her?"

We were sitting in the living room of Kulkarni's elder sister, writer Sudha Murthy, in Bangalore. Sudha is married to Infosys founder N R Narayana Murthy, so the reference to the Infosys stock seems entirely in place.

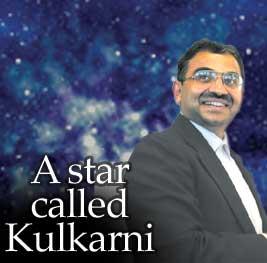

Kulkarni is Professor of Astronomy and Planetary Sciences at Caltech or the California Institute of Technology. In his mid-forties, he is a world renowned name in astronomy.

He migrated to the US 25 years ago after he completed his MSc in physics from the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. He says he will never return to live in India, but is all set to use his telescopes and knowledge to teach schoolchildren in India about the universe.

"One can in some ways compare this to (the May 1998 nuclear tests at) Pokhran," continues Kulkarni. "Despite the adverse commentary it attracted from the Western world, it created a sense of pride and solidarity amongst Indians. It is true astronomy calls for heavy investment. But if India stops investing in it, the country is bound to regret the decision."

Kulkarni is on his annual visit to Bangalore where his mother and sisters Sunanda and Sudha live. The highlight of his visit to India this time was a meeting with President A P J Abdul Kalam. "My brother-in-law [Narayana Murthy] told me the President had told him he would like to meet me whenever I was in India," he says with boyish enthusiasm. "So I flew to Delhi and had such a delightful meeting with him. I never meet politicians as a rule, but this man is so refreshingly different!"

Kulkarni, the youngest offspring of the Kulkarni family, was born and brought up in Hubli, north Karnataka. His eldest sister Sunanda followed in their father's footsteps and is a gynaecologist at a government hospital in Bangalore. Sudha, of course, is an accomplished Kannada writer and heads a charitable foundation funded by Infosys. Their younger sister Jayshree -- an IIT-Chennai alumnus -- is married to Boston-based IT billionaire Gururaj 'Desh' Deshpande.

"All my sisters were gold medallists and evolved into competent professionals," he remarks. "Coming from such a family, I found it strange there were so few women in high places in the US when I first moved to that country. I hear half the students in Indian medical colleges are female now. That percentage does not hold good for the US even now," says Kulkarni who married Japanese biochemist Dr Hiromi Komiya.

"All my sisters were gold medallists and evolved into competent professionals," he remarks. "Coming from such a family, I found it strange there were so few women in high places in the US when I first moved to that country. I hear half the students in Indian medical colleges are female now. That percentage does not hold good for the US even now," says Kulkarni who married Japanese biochemist Dr Hiromi Komiya.

He has won several awards for his work, including the US National Science Foundation's Alan T Waterman Prize, which is given once a year to the most accomplished scientist/doctor/engineer under the age of 35 working in the US, and the Presidential Young Investigator Award, a certificate from the US president, given by the US National Science Foundation for new faculty members on the basis of future promise.

He has won the Jansky prize, awarded each year by the Trustees of Associated Universities, Inc, for outstanding contribution to the advancement of astronomy. The prize is named in honour of the man who, in 1932, first detected radio waves from a cosmic source. Karl Jansky's discovery of radio waves from the central region of the Milky Way was the foundation stone for the science of radio astronomy.

Kulkarni won the American Astronomical Society's Helen B Warner award, which is given to an astronomer in North America under the age of 35 who has made outstanding contributions to astronomy and astrophysics. He also has the honour of being named a fellow of prestigious international societies including the American Astronomical Society, the Royal Society and the National Academy of Sciences for his pioneering research in astronomy.

His primary interests are the study of compact objects (neutron stars and gamma-ray bursts) and the search for extra-solar planets through interferometeric and adaptive techniques. He is also a part of Caltech's Space Interferometry Mission, scheduled for launch in 2009, will determine the positions and distances of stars several hundred times more accurately than any previous programme. This accuracy will allow SIM to determine the distances to stars throughout the galaxy and to probe nearby stars for Earth-sized planets. SIM is being developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory under contract with NASA.

As we moved between Sudha's living room and her son Rohan's bedroom, where we surfed on Rohan's PC, the conversation flowed easily from astronomy in the US, to whether India needs to be at its cutting edge, to what made the Kulkarni siblings such focussed people to how Srinivas fell in love with a beautiful Japanese woman two decades ago.

"My father was a man who measured output purely on the basis of work done," he recalls, his tiny moustache waggling up and down as he speaks. "Besides, if you are one of four siblings, you are under tremendous pressure to compete and prove yourself. I feel sorry that children like my daughters, Anju and Maya, who belong to two children families will never experience the positive benefits of this kind of pressure."

It was only after his daughters told him a couple of years ago that they could never see themselves as Indians that he finally took US citizenship. "Until then, I kept toying with the idea of coming back. But Indian science institutes are so politicised that I got discouraged," he says. "Transparent and fair managements simply do not exist in Indian universities."

It was only after his daughters told him a couple of years ago that they could never see themselves as Indians that he finally took US citizenship. "Until then, I kept toying with the idea of coming back. But Indian science institutes are so politicised that I got discouraged," he says. "Transparent and fair managements simply do not exist in Indian universities."

He first went to the US to do a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, 25 years ago. It was here that he met Hiromi, a doctoral student from Japan. He promptly learnt Japanese in a short few weeks and wooed the pretty Japanese student. He never thought twice about any possible cultural disparities. "At that stage, you don't think at all about such things," he laughs now.

He never thought about it even later on, but admits to having stopped speaking Japanese once he married Hiromi, as he found it far easier to communicate in English. His daughters speak adequate Japanese, but know no Indian languages. Both of them learn Bharata Natyam in California.

This unusual man brings to his dealings with his students the same clarity and sincerity with which he seems to face life. 'I am usually quite bad about returning phone calls,' he writes on his web homepage. 'If you need to reach me urgently please call my secretary.'

His homepages contains other brutally honest bits of advice. Here's a sample: 'Many students continue from undergraduate college to graduate school as a matter of course [inertia]. I have consistently advised my undergraduates to take a year off and join the Peace Corps or become a programmer in a commercial outfit or travel and then join graduate school only if the urge persists. I hope you are aware of the abundance of astronomy PhDs. Join the programme only if you are determined to become a great astronomer.'

As we chatted on, Rohan, whom his parents once admitted to calling by the pet name of Bill after the Microsoft founder, walked in and out of his room. A student at Cornell University, he took a quick peek at the PC monitor when a friend messaged him insistently and quickly typed a one line reply explaining it was his uncle online. His sister disappeared behind a curtained alcove, brushed her teeth, changed into a trendy pair of jeans, and got ready to go out.

"We are automating a telescope at Caltech shortly," says Kulkarni dreamily. "I hope to set aside an hour of telescope time every night during which Indian schoolchildren could see planets and such bodies in real time and not just as images. It would be daytime, and school time, in India at that time, you see. Dr Kalam was quite taken up with this idea. Now, all we need is someone who can co-ordinate this endeavour."

Does Kulkarni, a pioneering astronomer himself, subscribe to the viewpoint that the Indian information technology industry, led by men like his famed brother-in-law, is anchoring India firmly in the mire of drudgery instead of creativity?

"No, I think we should look at ourselves with humility and not be arrogant about our capabilities," he says at once. "We should start from a low point and work our way up from there. There may be many smart Indian minds here, but we are not an entire nation of brilliant people, right? As I see India just once a year, briefly, I can see it clearly in snapshots and recognise what reality is here."

Image: Rahil Shaikh