Home > News > Specials

The Rediff Special/Ehtasham Khan

August 15, 2003

It is like homecoming for a Pakistani Muslim family who stay with the same Hindu family in New Delhi every time they visit India.

They pull each other's leg, crack jokes and bond under one roof.

They go out shopping and select gifts for each other.

Both families visit the Red Fort, Chandni Chowk and the Qutab Minar.

Three full-fledged wars, Kargil and the disagreements between the governments of India and Pakistan in the last 56 years has not affected their relationship. The Suris of India and the Ashrafs of Pakistan have been friends since 1962.

The Suris belong to Lahore in Pakistan, but now live in Delhi. The Ashrafs, who lived in Gurdaspur in India, now live in Lahore.

Both families migrated during Partition. But the distance and persistent hostility between the two nations could not dent their relationship.

Their bond, in fact, has only grown stronger.

Says Mohammed Ashraf, 61, who owns an import-export business in Lahore: "We are like brothers. We have become closer with the passage of time."

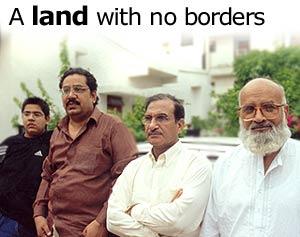

Ashraf (right in photograph above), who sports a white beard and a seemingly permanent smile, looks at Anil Suri and grins, "What do you have to say, Anil?" They hold each other's hands and burst into laughter.

Suri's elder sister is married to Ashraf's London-based friend, Mehboob Nasir.

This is Ashraf's fifth visit to India. On each visit, he stays with the Suris in their four-bedroom house in south Delhi's Kalkaji neighbourhood.

Suri, 47, a real estate dealer (second from left with his son, extreme left in photograph above), and his family first met the Ashrafs in London, where both families lived until 1962. Suri later settled in Delhi and Ashraf went to Lahore.

During his current visit -- he is part of a Pakistani business delegation to Delhi -- Ashraf is accompanied by his friends, Mehboob Alam (second from right in photograph above) and his wife Safia. All of them live in Suri's home.

"Agar apna ghar ho to koi hotel mein kyun jaye? [When we have a home here, why should we stay in a hotel?]" asks Ashraf. "This is like my home. The roads, the people, the language, the clothes -- everything here is so dear to me. Nothing is alien. Can I feel like this in any other country of the world?"

Alam, who owns a wedding and banquet hall in Lahore, echoes his views. "We have a personal relationship with Anil. We are not bothered what is happening at the government level."

"There is no difference between the people of the two countries," Alam, on his maiden visit to India, adds. "We have common problems. The fight is only among the politicians. A common man wants peace and harmony, which will ultimately benefit the masses. There should be more travel links and people from both sides should meet each other frequently."

Apart from business, what brought Ashraf to India is his liver problem. He has been taking medicines from an Ayurvedic doctor in Delhi since 1982.

"It has saved my life. Anil keeps sending me the medicine regularly. He sends it through a relative living abroad because there is a lot of checking at the India-Pakistan border," says Ashraf.

This time, Safia traveled with her husband to consult the same doctor.

"Increased trade relations will help dissolve political problems," Suri feels. "Both countries could benefit by enhancing economic relations like the European Union. If they do so, the winners are the people."

The friends think the media on both sides could help reduce the tension.

But Alam has a complaint. "The media on both sides are biased. They have the responsibility of convincing the governments to work for peace. They are not performing their duty," he says.

He uses the example of the Bollywood blockbuster Gadar – Ek Prem Katha. The film, which is set during Partition, is about a Sikh (played by Sunny Deol) who saves a Muslim woman (Amisha Patel) from an angry Hindu mob and marries her. When the woman learns that her family, whom she believed dead, is safe in Pakistan, she visits them. Her family refuses to acknowledge her marriage or allow her to return to India. The man goes to Pakistan to rescue his wife. Her family asks him to covert to Islam. He agrees. He is then asked to rant against India. He refuses and returns home with his wife after destroying all those who tried to stop him.

"Why do you make such films that divide people?" Alam asks.

"Look at the film's positive point," Suri says. "The Sikh agrees to convert to Islam. He attacks the Pakistanis only when he is asked to shout anti-India slogans."

"That may not be the reality," Alam replies. "You come and see Pakistanis are not like that."

Suddenly, there is tension in air.

"We don't discuss politics," says Ashraf. The others agree.

Suri recalls his only visit to Pakistan in 1997. A philatelist, he was invited to attend a philately exhibition in Lahore to mark Pakistan's 50th anniversary.

"I was a member of the jury and gave away prizes," says Suri, a member of various international philately organisations and a gold medalist in nine world philatelic competitions. "I can never forget those moments. I was never honoured so much in my life."

His most memorable moment that trip came when he 'visited' his family's ancestral home at Mall Road in Lahore. "I saw it from a distance. I didn't go inside. It is now owned by others. I ask about its well-being from Ashraf." He brought back photographs he had taken of his ancestral home instead.

Suri's memories make Ashraf nostalgic. "My greatest desire is to see my ancestral home in Pakhowal village in Gurdaspur in Punjab. I couldn't get a visa to visit the place. I want to take a movie camera and film the entire area." Born in Faislabad, Pakistan, he spent his early years in the village.

In Pakistan, Ashraf says he remembers India for her language and culture. "If somebody speaks good Urdu in Pakistan, we say he has come from Delhi. When somebody uses very courteous language, we say he has come from Lucknow."

Ironically, Urdu is Pakistan's official language.

Alam says the average Pakistani hardly speaks about India, though they consider their neighbour a great country with a better economy and technology.

Bollywood is a hot favourite, he says, with Shah Rukh Khan and Aishwarya Rai topping the Pakistani list of favourite film stars.

"Ordinary people have problems of their own," he says. "They don't have time to discuss the India-Pakistan relationship. But everybody wants peace. Once the political problems are over, people from both sides will meet each other with open hearts."

The major problem, Alam feels, is Kashmir. "Once the Kashmir problem is over, then there is no dispute at all," he says.

Suri does not agree. "Why not leave Kashmir aside and talk of peace and better economic relations?" he asks.

Once again, the atmosphere becomes grim.

"We don't discuss politics," Suri says to disssolve the tension.

What have Ashraf and the Alams done since their arrival in Delhi?

"We go shopping. Indian saris and jewellery are much sought after in Pakistan. We have seen many historical monuments," says Alam. Many members of the Pakistan business delegation caught up with Indian movies.

"We don't get to see Indian movies in cinema halls [in Pakistan]. Watching Indian movies on the big screen is an entirely different experience," one woman delegate had said earlier. "Back home, we see these movies only on

television."

Ashraf, Alam and Suri look forward to the day when people visiting the other side of the border will not require visas. "I hope a day will come," says Alam, "when you go to the border, show your passport and the other side will say, 'Please come in.' "