Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy's next film is about aging Pakistani musicians who get a second chance because of jazz.

Karachi-based Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy is the first Pakistani to have won an Oscar, for her 2012 short film Saving Face.

Now Obaid-Chinoy is back with an upbeat film that looks at the lives of Pakistan's aging musicians who get a second chance in their career. She co-directed Song of Lahore with filmmaker Andy Schocken.

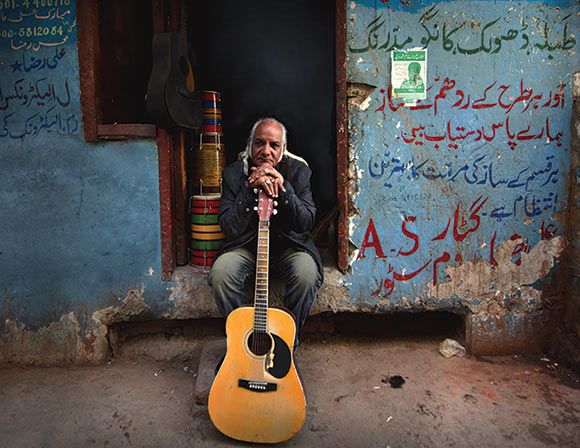

Song of Lahore looks at the musicians who work out of a studio in Lahore. Their best-known work -- a Pakistani rendition of Dave Brubeck's Take Five, with sitars, violins and tablas became an Internet sensation.

In the film they bring their work to New York and collaborate with Jazz at the Lincoln Center's ensemble.

Song of Lahore had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival. Aseem Chhabra spoke to Obaid-Chinoy over the telephone before the start of the festival.

I thought the film was lovely. It did remind me of Buena Vista Social Club since there are a lot of similarities between what happened to music and arts in Pakistan and in Cuba.

A lot of people who read the description say it sounds like Buena Vista Social Club. It is a similar story.

Why did you use the title Song of Lahore? What kind of thought went behind that?

Song of Lahore is an ode of Lahore. The musicians are from that city and Lahore was the cultural capital of Pakistan.

I have a special connection with Take Five. It was a one of the first jazz pieces I heard when I came as a student to the US. So tell me how did this project come about?

I heard about the Sachal Ensemble years ago and I was very interested, because I grew up with stories from my grandfather about musicians playing on the streets of Karachi on Sunday evenings and bands. People walking around and this lovely energetic vibrant society that my grandparents were a part of.

Unfortunately I was born in the Zia-ul Haq era and I never witnessed the bands and the recitals.

And so when I heard that there was an orchestra that had come together in Lahore I was very intrigued by them. When I researched about them I realised that this is a story that needs to be documented.

I didn't know what the story was going to be at that time since it was a group of people who had come together to preserve Pakistan's musical instruments, the instruments of the region and they were recording a lot of local music.

But when I started interviewing them I realised that they were doing something very special. Music has always excelled because of patronage. In the Zia era the patronage ended and the audience shrank. Many of the musicians who used to hand their art from one generation to the next stopped doing that.

Instead they encouraged their children to open a store or to go to school to get an education to essentially work somewhere. Their livelihoods had been affected and they didn't want their children to suffer.

Because we were not going to have more violin players, the story was about how we were going to preserve Pakistan's musical heritage as well. Will my children grow up with a sitar or a sarod player in their midst?

From the Take Five video to the invitation to Jazz at the Lincoln Center -- that is quite a journey!

While we were filming, they had already released the Take Five video and it had become an Internet sensation. We document that phenomenon and then the group received a call from Wynton Marsalis. It was an incredible surprise for all of us.

When Dave Brubeck was alive he wrote to Izzat Majeed who is the founder of the Sachal Studio Orchestra and he told him that it was one of the most interesting renditions of Take Five he had heard. Quincy Jones wrote to him as well. We knew that people who were of merit in the jazz world were noticing the group.

And then with Wynton Marsalis' call the musicians flew to New York. But these musicians don't read music, because they count music. They don't know Western notation of music and they don't speak English. So working with the big brass band at the Lincoln Center, with just four days of rehearsals -- you could see the tension whether it would work or not.

As a filmmaker it is incredible when you watch a story unfold in front of your eyes that you cannot predict. You cannot predict the ending. With Song of Lahore that is exactly what happened. The story brought us to New York and then back to Pakistan.

How many musicians came to New York for the show?

We had six musicians for the show.

And then they had to find a sitar player who miraculously become a part of the group. Was he Pakistani or Indian?

He's an Indian sitar player living in New York. It was great that they could play together because our instruments are the same.

Even as the audience when you watch the film you must be thinking will this work or not? And you see the relief on the faces of the musicians when he actually plays the sitar. Everyone had a collective sigh of relief.

They played popular jazz tracks like Take Five, but they also played music from Pakistan -- raags and compositions that Wynton and his band incorporated. They played Mahi Ve, Leher Walley Pul Par.

How many shows did they have at Lincoln Center? I wish I had watched them perform.

There were two sold out shows. They got standing ovations on both nights.

Will they perform again in the US?

The plan is that as the film makes the rounds of the festival circuits they will perform again in New York.

But the US State Department is bringing them during the Tribeca Film Festival. Izzat Majeed, who organised the group, grew up listening to all the musicians who were part of the Jazz Diplomacy programme as the performers came to Pakistan.

Dave Brubeck and Dizzy Gillespie came to Pakistan to perform. To see them live it must have left a huge impression on him.

So we think it is incredible that some sort of reverse diplomacy is taking place now. The Pakistanis are bringing their music and instruments to the US now.

I think what's really interesting is in Pakistan the film and music industry is coming back in a big way.

Yes. It's fascinating.

Tell me about working with Andy. How did you connect?

Andy and I were connected by Daniel Junge, who was my co-director for Saving Face. Andy had filmed several of Daniel's projects. He was a primarily a cameraman who had co-produced a number of projects, but he was looking to direct something and the partnership has been incredible.

To make a film that spans over two-and-a-half to three years -- it's filmed in Pakistan and the US -- it was a big project and it required me to have a partner who had the love for music and the musicians, but also understood the complexities of filming in both these worlds.

He bonded quite a bit with the musicians. They opened up to him in a different way than they opened up to me. The musicians are not used to having a woman among them. It was great to see them divulge some things to them that were different from what they told me.

A film is not made by one person. It is a collective effort. It's great to have a partner who understands and appreciates what we were able to put together.

Did Andy come to Pakistan?

Yes, he came twice to Pakistan and then he handled the musicians' visit to New York.

So what is their status in Pakistan? Are they performing regularly?

Yes, they are. They recently performed at the Lahore Music Festival and in May they will perform in Karachi. They were in India a couple of months ago and they performed in Delhi. Their Mumbai concert was canceled by the city's police saying they didn't have a permit. The Delhi show was a sold out performance.

REDIFF RECOMMENDS

© 2025

© 2025