'Action was no longer a resolution mechanism, a punishment meted out to the villain at the climax. The fight now came right in the initial scenes and was often used to set up the hero's character. And the hero did not fight with his fists alone; he brought his anger and his psychological scars into battle.'

'This was a common pattern in Salim-Javed's scripts: the action scene would be announced much in advance and the tension kept simmering till it exploded into the actual fight.'

A fascinating excerpt from Diptakirti Chaudhuri's book, Written By Salim-Javed: The Story Of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters.

'The leading exponents of the current screen cult of bloody reprisals are scriptwriters Salim and Javed, whose none-too-original scenarios only succeed in stating the obvious: That the defence against violence must always be more violence... Sholay manages to raise screen violence to almost unimaginable heights.'

-- From K M Amladi's review of Sholay in the Hindustan Times, titled Uncensored Violence

'The film could have gone easy on the depiction of the violence. There is a pronounced sadistic touch to the last-reel encounter between Sanjeev Kumar and Amjad Khan's villain, the episode having the sort of violence that borders on the sickening.'

-- From Bikram Singh's review of Sholay in Filmfare

Sholay had violence well above what the average Hindi cinema audiences were used to in the 1970s.

Starting from the train robbery right in the beginning to the gritty shoot-out in the climax, the film is full of violent scenes. But there is hardly any blood. Despite bullets flying thick and fast, bandits and bystanders being cut down every now and then, there is no sign of the diluted version of tomato ketchup that we have now got used to.

The first signs of blood are introduced in the very last scenes when Thakur uses his nail-studded shoes to squash Gabbar's hands to a pulp.

A major reason for this was to keep the censor board at bay but, as it turned out, the impact was more devastating this way. Because the violence was psychological.

Cutting off a proud man's arms is such a distressing act of violence that one doesn't have to show the severance in all its bloody, gory glory.

The horror of a whole family being wiped out is again not linked to the extent of bloodshed. Especially when a child's head is blown off from point-blank range.

Even Ahmed's death -- a shocking end to a young man with potential -- is not shown but symbolised through the killing of an ant.

Each one of these scenes is unimaginably violent without focusing on the actual act of violence.

In many ways, Sholay marked the pinnacle of the series of violent films that Salim-Javed were accused of writing. Sholay's violence was a 'choreographed ballet' that was created with the help of mega-budgets and foreign technicians and equipment.

However, Salim-Javed's forte was not the elaborately mounted 'fight scene.' In fact, the real speciality of this dynamic duo was conjuring the kind of violence that played on your mind rather than the sort that played out only in front of your eyes.

Salim-Javed focused on creating a context that affected the audience's psyche and made the actual fights seem far more impactful. The physical violence was accentuated by psychological violence, and this was often achieved long before any punches were actually thrown.

Action was no longer a resolution mechanism, a punishment meted out to the villain at the climax. The fight now came right in the initial scenes and was often used to set up the hero's character. And the hero did not fight with his fists alone; he brought his anger and his psychological scars into battle.

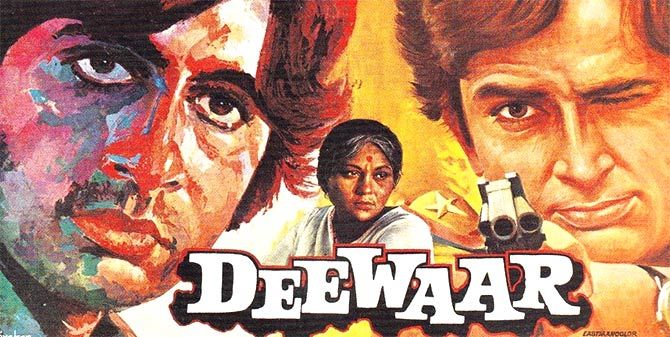

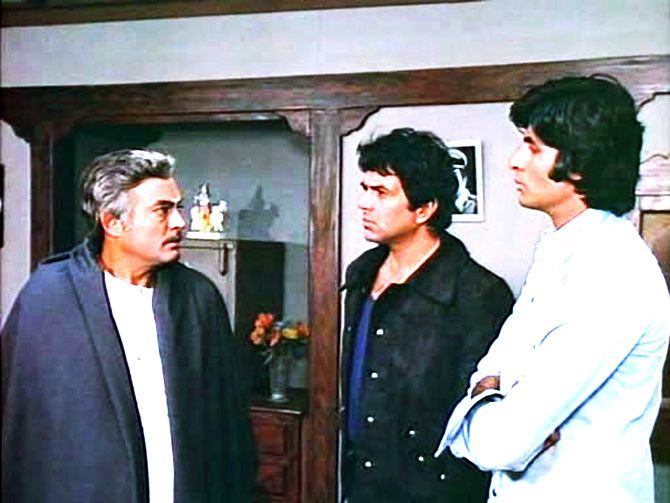

In Deewaar, when Vijay Verma fights Peter's goons in the famous scene at the dockyard warehouse, we can sense that his manic anger is not just against these goons (with whom he has no history). He is channelling his anger against the father who abandoned him, a society that thought nothing of punishing a little boy for his father's sins, and a system that is failing him and his brother.

At the end of it, when his mother asks why he didn't avoid the fight, Vijay's angry retort is exactly what the audience has been thinking all this while. 'Tum chaahti ho main bhi mooh chhupake bhaag jaata (You wanted me to hide my face and run away)?'

Deewaar had just this one fight scene but the film always comes across as exceedingly violent because, in the viewers' minds, Vijay starts getting beaten up the day the disgruntled workers tattoo 'Mera baap chor hai (My father is a thief)' on his arm. It is only now that he is able to give it back and begin the process of finding some sort of closure.

This was a common pattern in Salim-Javed's scripts: the action scene would be announced much in advance and the tension kept simmering till it exploded into the actual fight.

In Zanjeer, during Inspector Vijay Khanna and Sher Khan's confrontation in the police station, the police officer -- in an unprecedented move for a Hindi film hero -- kicks the chair the crime boss is about to sit on.

Their tussle begins right then with Sher Khan taunting Vijay that it is only because of the safety of the station and the security his uniform affords him that he can dare to do such a thing. Vijay picks up the gauntlet, walks into Sher Khan's ilaaka (territory) sans uniform and challenges him to a bout.

The high-voltage fight scene actually takes up only a couple of minutes of screen time but it was written as a wellpaced, crackling-dialogue-laced event that seems to last longer on screen and even longer in our memories.

It ends with Sher Khan acknowledging the new hero -- 'Aaj zindagi mein pehli baar Sher Khan ki sher se takkar hui hai (This is the first time Sher Khan has fought someone just as brave)' -- and bringing the episode to a satisfying close.

In Trishul, Amitabh Bachchan's devil-may-care character acts in a similar fashion when trying to evict Madho Singh (Shetty) from the land that he has bought.

The standard Hindi film action sequence -- where the hero beats up and throws out the villain -- is preceded by a sequence that builds the tension, with Vijay walking up to Madho Singh and asking him to leave. Then, of course, he returns with an ambulance to pack the beaten villains into.

Again, the violence is made memorable by introducing dialogues and other elements that accentuate both the action and the character.

In a way, the violence in Trishul is set up by the way Vijay is introduced in the first scene where he lights a dynamite fuse with his beedi and calmly walks away from the danger zone.

You get an inkling of the impending violence from the manner in which he explains his fearlessness: 'Jisne pachees baras apni maa ko har roz thoda thoda marte dekha ho, use maut se kya dar lagega (If someone has seen his mother die a little every day, why would he fear death)?'

The most protracted build-up of an action sequence in a Salim-Javed film was in Kaala Patthar, where both Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) and Mangal (Shatrughan Sinha) were presented as diametrical opposites, shown to be getting increasingly angry with each other, and finally pitted against one another in a pitched battle.

Incidentally, this fight (which happens just before the interval) is preceded by two near-skirmishes between the two heroes, both triggered by insignificant things like a matchbox and a cup of tea. Both incidents are defused in the nick of time by Ravi (Shashi Kapoor), but it all adds towards the explosion of the final showdown.

Not all of Salim-Javed's orchestrated fight sequences were serious, though.

In Don -- a film where the mood was more light-hearted -- Vijay/Don taunts villain Shaakaal (played by Shetty) repeatedly in a police van. By now the audience knows a fight is coming, which will facilitate the gang's escape and bring about the climax, and it is brought on by a series of wisecracks made about Shetty's supposed cowardice.

In Deewaar, Kaala Patthar and Trishul, as in a few other films, the initial fight is the biggest action sequence of the film; the first two do not even have a 'resolution fight' at the climax, and the one in Trishul seems distinctly tamer than the 'ambulance' scenes.

As macho heroes became more and more popular in the late 1970s and 1980s, this became a template for action films, where there was always a fight scene to introduce the hero or set him up as one.

Film writer Jai Arjun Singh talks about Deewaar but it could well be about some of the other Salim-Javed classics when he says: 'The movie's power draws as much from its silences as from its flaming dialogue, and the writing of Salim-Javed, in conjunction with Bachchan's incomparable performance, take it to heights Indian cinema has rarely touched since. The power of Deewaar lies in its ability to make us feel the tragedy rather than present it to us all gift-wrapped on a platter.'

Having said this, Salim-Javed did popularise the genre of Hindi film where the 'fight scene' was no longer a pre-climax formality in which the bad guy is given some half-hearted punches as punishment before being taken away by the police.

Since most of their scripts were based on the premise of revenge, they brought in the concept of what film historian Kaushik Bhaumik calls 'proportional justice.'

Bhaumik gives the example of Yaadon Ki Baaraat where the violent manner in which the villain Shaakaal is killed is similar to the brutal way in which he murdered the heroes' parents. He meets his end near a rail track, a setting reminiscent of the one where the parents are murdered and the three brothers get separated.

Even in Zanjeer, Vijay's parents are shot dead by Teja on the night of Diwali, the firecrackers drowning out the gunshots. When Vijay arrives at Teja's den to take revenge, it is yet another Diwali night.

In a way, the blood and gore of destroying Gabbar's hands in Sholay is also an instance of 'proportional justice.' Gabbar cuts off Thakur's arms and he, in turn, orchestrates the retribution in which Gabbar's hands are rendered useless. The sudden appearance of blood in that scene seemed to underline the completion of this quest for justice.

Incidentally, the climax of Sholay was supposed to have been even more violent, with Gabbar being impaled to death.

The Emergency-era censor board refused to allow the depiction of a former police officer taking the law into his own hands. Hence, the death and Thakur's guttural screams were replaced by a tamer version where the police force walked in and arrested Gabbar.

The original version is available quite freely on YouTube and is a gut-wrenching watch. Sanjeev Kumar's measured performance throughout the film has a tragic conclusion when he breaks down and cries at his 'victory.'

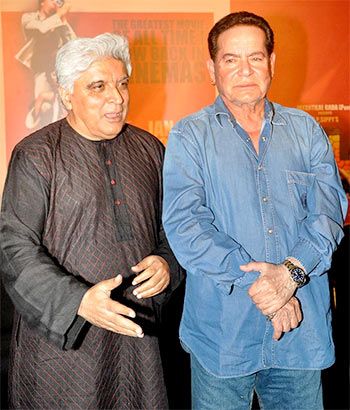

By and large, the anger of Salim-Javed's (seen, left) heroes was the result of some serious psychological hurt that was as violent on a mental level as their action sequences were on a physical level.

By and large, the anger of Salim-Javed's (seen, left) heroes was the result of some serious psychological hurt that was as violent on a mental level as their action sequences were on a physical level.

Be it the tattoo in Deewaar or an 'illegitimate father' in Trishul or a distant father in Shakti, the resulting psychological violence inflicted on the hero returned to wreak vengeance and this translated into extremely violent action scenes whose impact was far greater than the screen time they occupied.

In many films this impact was further heightened by the intensity that the writers' favourite -- Amitabh Bachchan -- brought to the fight scenes. Salim Khan says, "Amitabh Bachchan is physically very weak in real life, but he projects aggression amazingly well. When most heroes pick up a gun, they look as if they don't really know how to handle it and the gun may go off accidentally. But when Amitabh picks up a gun, it seems that he really means business."

At a time when the industry had given up on Bachchan, Salim-Javed were the only ones who kept their faith in him. And coincidentally, it was a fight scene in which they noticed the actor for the first time.

Bachchan recalls, "I had a fight scene in Bombay To Goa where I fight while I am also chewing gum. I get punched in the face, roll over and get up, still chewing gum. Salim-Javed had found this scene quite impressive."

A cursory fight scene in a not-so-successful film was what hooked the writers and inspired them to tie their fortunes to that of a struggling actor. And eventually their gamble paid off: the actor became Hindi cinema's first action hero and Salim-Javed were 'credited' for bringing in a wave of action in Hindi films.

As they say, it is all written!

Excerpted from Written By Salim-Javed: The Story Of Hindi Cinema's Greatest Screenwriters by Diptakirti Chaudhuri, published by Penguin India, with the author's permission.

© 2025

© 2025