A year has passed since Shashi Kapoor passed into the ages.

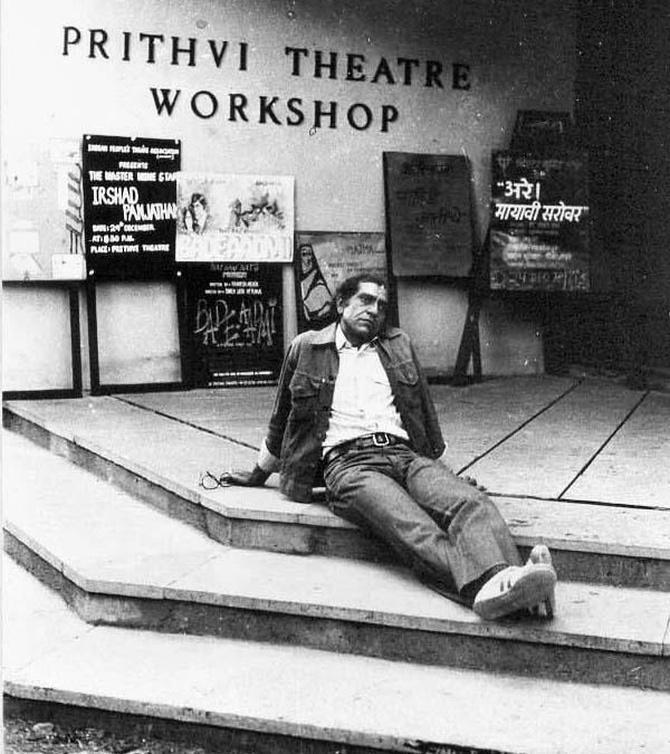

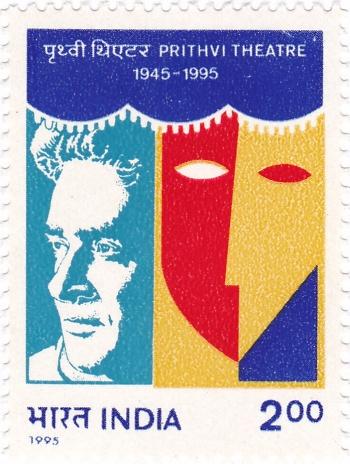

His movies live on on television, but Shashiji's greatest legacy must remain Mumbai's Prithvi Theatre, where people came to be entertained, informed and, perhaps, also enlightened.

Arundhuti Dasgupta discovers the Prithvi magic.

Kunal Kapoor stares quizzically when you ask him about the business of running Prithvi Theatre, a 40-year-old institution that has become an iconic subset of Mumbai's cultural legacy and the country's theatrical heritage.

"There is no business. Period. No question of a business model or any such thing," says Kapoor who runs the show at Prithvi, a theatre that his parents Shashi and Jennifer Kapoor set up in the 1970s.

For the former adman and member of a large film family that spans several generations, the theatre is a labour of love, one his grandfather envisioned and his parents nurtured.

He took over the running of the place from his sister Sanjna in 2012.

Although he was always around, that was when he decided to get more hands on and his sister moved on to work with her travelling theatre company, Junoon.

Business or running the theatre for a profit, desirable though it may be, is not Prithvi's raison d'etre.

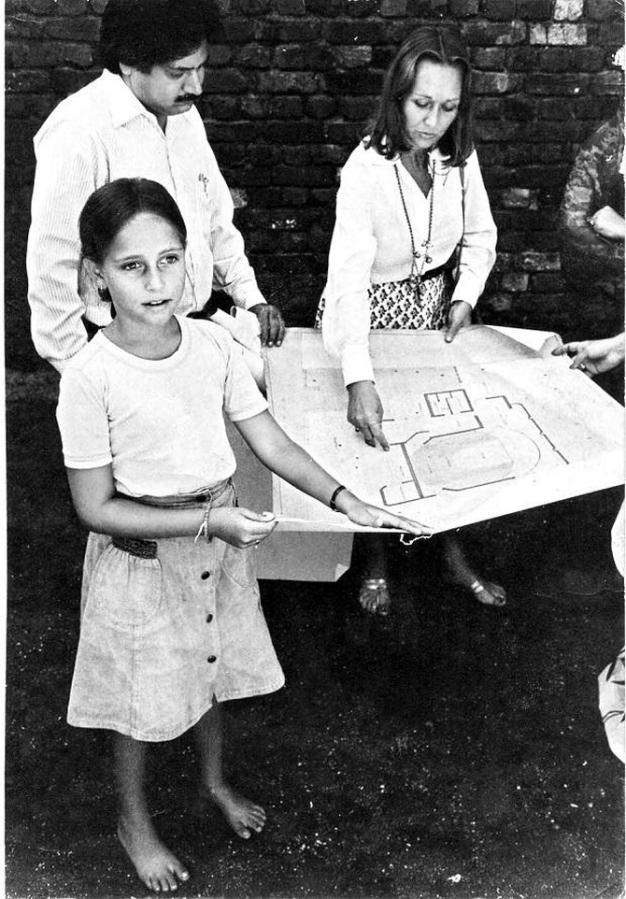

"Ask why Prithvi was built?" he says. The theatre that saw the curtains go up the first time on November 5, 1978 was meant to revive the arts and audience interest in drama.

Shashi and Jennifer, both successful actors on the big screen, were theatre lovers and wanted a small space that would nurture the fraternity of actors, writers, technicians among others.

At the heart of the endeavour was a desire to build a place that was affordable for performers and audiences.

Kapoor speaks slowly, his accent clipped and his voice a hoarse whisper -- the effect of nights of partying or perhaps the thick smoke that hangs over the city at this time of the year.

He says that right from the start it was decided the rate structure had to be in favour of the performing groups, not the landlord. "That is the DNA of Prithvi Theatre."

Jennifer Kapoor, who ran the place since its inception till she passed away in 1984, is known to have encouraged many young actors, drawing them out of their dark corners to take the spotlight at Prithvi.

Her oeuvre was impeccable and her generosity is still the toast of the theatre community in town.

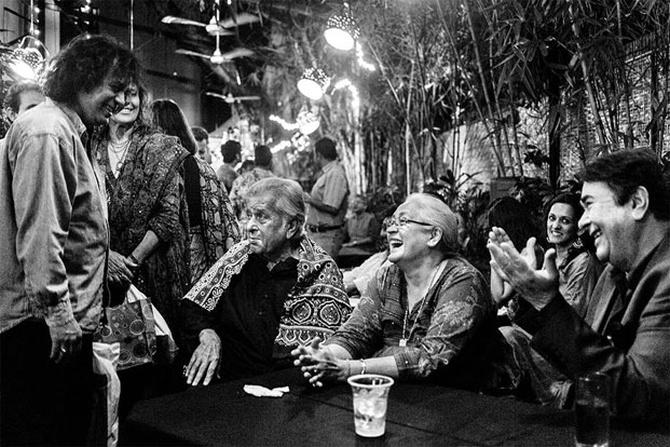

Amrish Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Ratna Pathak Shah, Sunil Shanbag, Makarand Deshpande and many others, you name a theatre doyen and there will be Prithvi on their timeline.

Naseeruddin Shah, who was in the first play staged at Prithvi (Udhwastha Dharmashala), is still drawing a full house in its 40th year and has said that Prithvi's biggest contribution has been to make the theatre a habit for its audiences.

The acknowledgement that Prithvi has had a role to play beyond the confines of its 200-seater auditorium is what gives Kapoor most pleasure.

He points to Arundhati Nag and her theatre in Ranga Shankara in Bengaluru. In his opinion, it is the only other place dedicated to the art and the craft of theatre.

Nag has said on many occasions that Prithvi is her inspiration.

For Kapoor, the arts are the hallmark of an evolved civilisation -- whether it was the Greeks, the Romans or the Aztecs.

What happens when you don't have the arts?

"I have just two examples for that: Genghis Khan and the Taliban," he says.

Kapoor wants to build Prithvi into an institution that outlives his generation and the next.

But what he would like most of all is more sensitivity from the government and from corporate patrons. The theatre gets no government grant and corporate sponsorships are hard to come by, primarily because they are tied to numerous invisible strings.

The team that runs Prithvi Theatre and the annual festival is selective about sponsors and picky about the deals they strike.

For one, the sponsor does not get naming rights over the festival; it is always the Prithvi Theatre Festival.

The 2018 festival was sponsored by Bank of Baroda, but unlike the Indian Premier League or the film festival (MAMI) that has the sponsor's name tagged to its label, the Prithvi festival keeps its identity.

Even during one of its longest running associations with Orange (now Vodafone), it was always the Prithvi festival.

Sponsors are reluctant to accept such an arrangement and many get tangled up in driving a bargain around footfalls or return on investment. They seek a tangible return for what is largely an intangible benefit.

Kapoor minces no words. "To think you can survive without art is stupidity."

He quotes his grandfather Prithviraj Kapoor who spoke in Parliament in 1955 and reportedly said that theatre is the greatest temple. He believed this is a place where religion, class or caste does not matter.

"We laugh together, we cry together and that is the beauty of the arts," says Kapoor.

The idea behind building the theatre was to create a place where people came to be entertained and informed and, perhaps, also enlightened. And at the same time a place where actors, directors, artistes found their metier and rejoiced in art.

When Prithvi Theatre opened, the price of a ticket was Rs 10 and every time a ticket was sold, the performing group contributed one rupee to the theatre.

That ratio is respected even today (tickets are now priced between Rs 250 and Rs 500) and the entire box office collection goes to the theatre group, says Kapoor.

"We don't rent out the theatre. No XYZ can hire us because he wants to hold a talk show on some religious concepts. We decide who performs here and we don't rent out by the hour. We are not a brothel," Kapoor says with a flourish.

The city could do with at least 25 to 30 more such spaces, he believes. There is an audience and there are enough performers to fill up the stage. But the economics makes it unviable.

"We have a very small team, just 15 to 16 people. A similar theatre in London has 138 employees," says Kapoor.

Prithvi is never dark. Except for Mondays, the day for maintenance and other sundry issues, there is a show every day, and on certain days, more than one show a day.

The show, after all, must go on, he says, smiling at the cliche.

© 2025

© 2025