If Indian storytelling can deliver, it can make the entertainment industry an engine of economic growth and a substantial contributor to GDP, says Vanita Kohli-Khandekar.

Circa 2010

The story goes that halfway through My Name is Khan, Director Karan Johar and lead actor Shah Rukh Khan figured that the tale of an autistic Indian's quest to meet the US president and tell him 'My name is Khan and I am not a terrorist' needed a studio that could reach beyond the Diaspora markets.

That was a tough ask for most Indian films. They approached Fox Star which grabbed the film and put all its muscle behind it.

My Name is Khan released across 1,400 cinema screens in 68 countries and was aired on television screens in 65 -- unheard of for an Indian film.

The film went on to earn over $100 million (on box office and TV), making it the biggest global hit from India till then.

Had our stories finally crossed over?

Circa 2019

In July 2018, Sacred Games, a Hindi show, began streaming in 190 countries to Netflix's 125 million subscribers (then). It was reviewed by every major publication in the world.

More than a year later in September 2019, it was nominated for the International Emmy Awards, along with Lust Stories (Netflix) and The Remix-India (Amazon Prime Video).

The same month, The Family Man premiered in Los Angeles before dropping into 75 million homes across the world on Amazon Prime Video.

The service now streams 12 Indian shows with another 30 in the pipeline.

"One in three viewers for these shows is from outside of India," says Jay Marine, vice-president, Amazon Prime Video.

Meanwhile, Sacred Games just made it to The New York Times list of the 30 best international series of the decade.

Yes, we have crossed over.

The kaleidoscopic effects of the chaos on-demand viewing created in the last decade are now settling down to reveal a clearer picture.

One in which telecom, technology, and media firms are collapsing into one simple search for audiences.

Google, Amazon, AT&T, Disney, Comcast, Apple, and Netflix, among others, are leading this search.

They are acquiring companies and commissioning content, not just in North America but from across the world in their search for scale.

It is a scale defined not just by having a massive platform, but by the ability to serve a maddeningly diverse yet global audience for entertainment.

It could be Indians watching Narcos (Spanish, American), the French watching Sacred Games (Hindi, India), Americans watching The Crown (English, Britain), or the Turks watching Dark (German, Germany).

Only by aggregating as many diverse audience clusters as they can will any of these giants remain in the reckoning or win the battle?

It is also not a scale defined by any technology.

Many of the movers and shakers have big, profitable, linear businesses. Disney controls three large OTTs (Hotstar, Disney + and Hulu), one of the world's biggest film studios, and a profitable pay TV business.

Comcast recently bought Sky, a DTH operator. Even when they don't have legacy businesses, Google's YouTube, Amazon, or Apple are about scale with diversity.

This search for audiences across geographies, technologies, languages, tastes, formats and devices is redrawing the entertainment map in several markets.

Sitting around global fireplaces

In this new ecosystem, India is represented not by its top media or telecom firms, but storytellers.

Unlike China, there are no quotas or restrictions on foreign films in India. Yet, more than 90% of the entertainment consumed is local.

In a world swamped by Hollywood, India's creative industries have stood their ground for 100 years.

It is, other than Korea, one of the few markets with authentic local stories to tell and an industry that tells them well.

Dangal, Gully Boy, Gangs of Wasseypur, Vicky Donor, Piku, Masaan, Andhadhun are just a few from the decade gone by, in Hindi.

There are scores in Tamil, Marathi, and Bengali, among other languages. This ability to tell compelling stories is what the world's largest platforms are turning to.

If the consumption of entertainment is a continuum, then on everything from YouTube to Netflix, Indian audiences and content creators are surprising the world.

At 1.8 billion users, YouTube is the world's largest streaming platform. It is an open, online auditorium where anyone can come in to show a talent, share information, expertise or simply post a video.

Yet it is an Indian music firm, T-Series, that has the most watched YouTube channel globally.

At the other end of the spectrum is Netflix which has single-handedly created the whole high-quality, subscription-driven, streaming market that led to a global wave of consolidation.

It has 18 Indian shows at various stages of development, in addition to the eight already streaming to its (now) 160 million members.

"India is our biggest market for content; we commission more from here than anywhere else. The more authentically local the storytelling is, the more likely we are to tap it," Ted Sarandos, chief content officer, said last year.

CEO Reed Hastings announced that over 2019 and 2020, Netflix would be spending Rs 3,000 crore (Rs 30 billion) on content from India.

Media Partners Asia estimates that online video players will invest $1.4 billion in content from India by 2024, a compound annual growth rate of 13% from 2019.

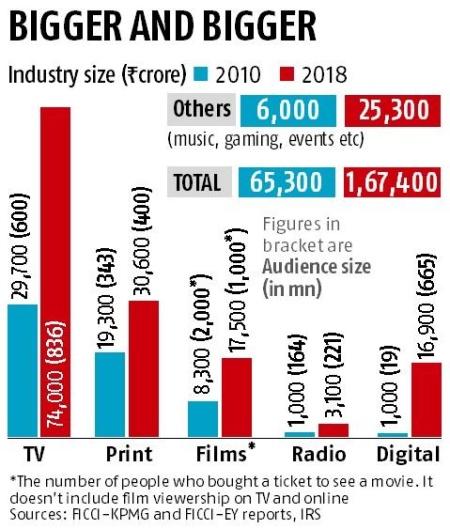

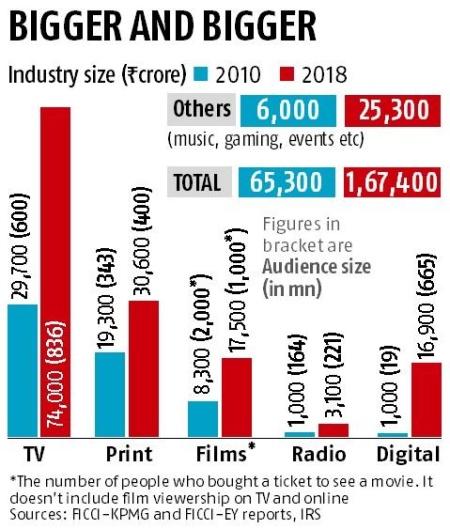

You could argue, rightly, that the Rs 74,000 crore (Rs 740 billion) Indian television industry, which offers 3 to 6 hours of fresh content every night on every major channel, commissions much more. It does.

But here is the catch. India is the world's second-largest television market, the largest film producing one, and the fastest-growing Internet market.

Yet its $24 billion media and entertainment industry, of which television and films bring 56%, is pathetically under monetised.

Look at the table of the top Indian media firms. For an entertainment crazy country of this size, these are really small.

Here is some quick perspective -- Disney (Star's parent) is almost three times the size of the entire Indian media industry.

The global demand for Indian stories then should help monetise them better. And the timing couldn't be better.

Everything that happened in the last decade -- crashing data prices, increasing number of devices, our exposure to global films and shows, higher connectivity -- has meant that Indian storytellers are more than ready for this.

Circa 2019

The hairy monsters? The first one is the sheer volume of content needed and whether the Indian industry is up to it.

Media Partners Asia estimates that from 400 hours in 2018, demand for original, film quality content on the top 10 OTTs is 1,000 hours in 2019.

That is the equivalent of making 500 films in addition to the 1,600 we already do. This means scaling up on talent, processes, writing and a whole lot of things, very fast.

The second is a regulatory environment that has become increasingly unstable. From tariff to content to valuation, regulators have been poking into everything making life difficult for the creative industry.

If Indian storytelling 'can deliver', it has the potential to make the industry what it should always have been -- an engine of economic growth and way more than a sub-1% contributor to gross domestic product.

EY estimates the Indian media and entertainment industry will reach $33 billion by 2021. If Indian stories crossover at scale that might be an underestimate.

© 2025

© 2025