Historically, Mumbai has been the cinema capital of India and for her to have a film museum of this kind was perhaps a natural happening.

Ranjita Ganesan reports.

A man, who appears to be in his early 40s, takes the stage somewhat gingerly, one hand stuffed shallow in his pocket. An acid green screen is behind him, and ahead are a contraption that senses motion and an audience of nine.

Each time he waves his free arm a certain way, a monitor shows him standing in new surroundings. A slow-striding tiger appears whose back he pats.

Next, he is beside a waterfall into which he dips his fingers. His poses get bolder in response to cheers.

When a luxurious bedroom and fireplace manifest around him, he pretends to shiver and rub his hands together.

This setup, which explains visual effects technology to visitors, is the most popular attraction at the recently opened National Museum of Indian Cinema in Mumbai.

It is unclear if everyone present in the room understands the exercise but enthusiasm is high. Encouraged by such participative spirit, Amrit Gangar, film historian and consultant curator for the space, says people are "visiting it, talking to it, singing with it, maybe dancing with it, (and) thinking with it as there are plenty of interactive possibilities".

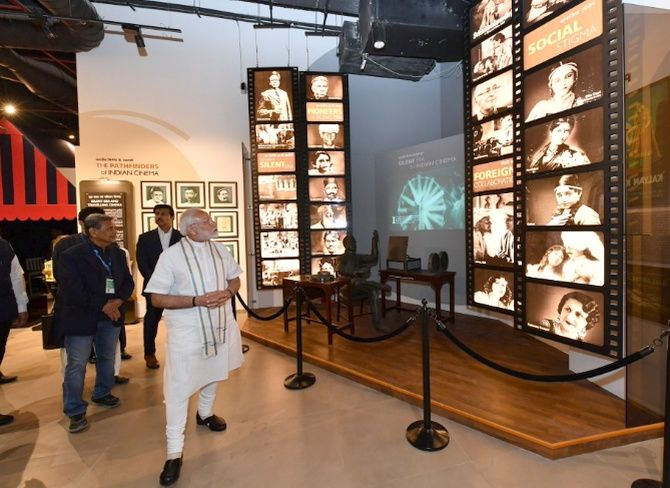

The Rs 156 crore (Rs 1.56 billion) project was built over several years, much before Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi made a flying visit to the city to inaugurate it.

It included the joint effort of the Films Division, the information and broadcasting ministry, the National Council of Science Museums and an advisory committee led by film-maker Shyam Benegal.

The idea began around 2003, and after several false starts in the last few years, has worked its way slowly out of red tape.

The museum occupies two buildings in the Films Division complex on Pedder Road, south Mumbai, first of which is the heritage Gulshan Mahal, once home to India's earliest woman documentary film-maker Khurshid Jairazbhoy.

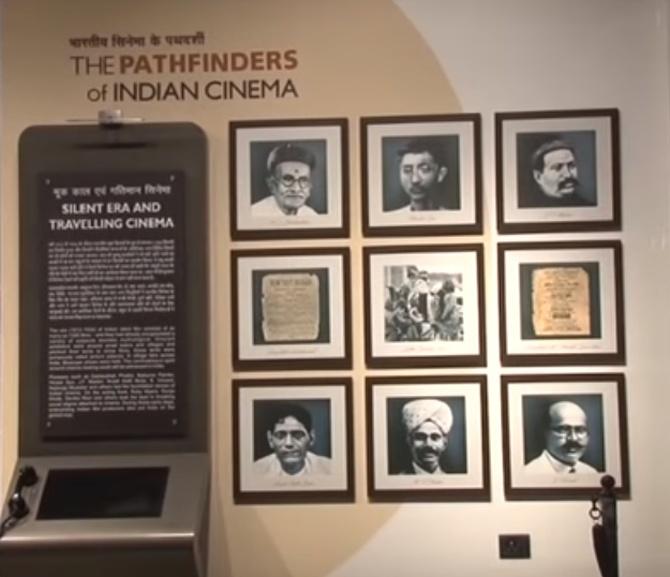

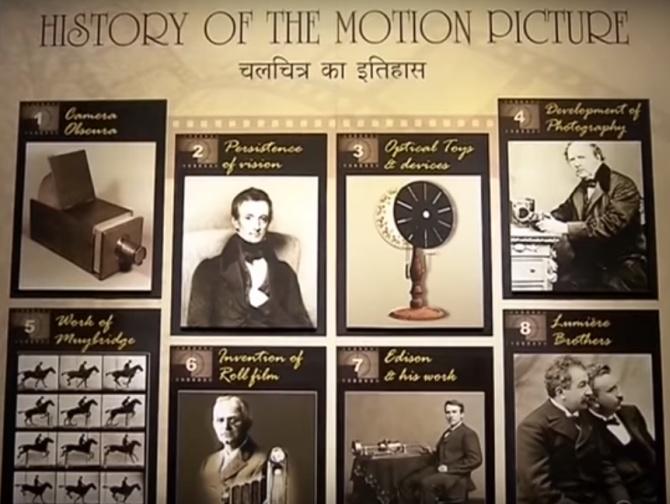

It had been restored to its Victorian-Gothic origins by 2013 and filled with historical displays. These chronologically tell of how cinema began and entered India, how silent films evolved from shorts to feature length, how after 1931 they lost ground to sound cinema. The mainstream and New Wave cinemas that rose thereafter are chronicled here.

Gangar, who came on board in 2012, likens the curators' role to that of an archaeologist. "To discover the Mohenjo-daro of movies" he had set off to cities and mofussil towns. Some artefacts came from private collectors including "Nakubabu" of Kolkata, over 90 years old yet able to tell stories about the studio era.

Replicas of the praxinoscope, mutoscope, magic lantern and vintage Arriflex cameras give a sense of how the tools of film-making developed.

The pictures changed too, from simple images of a galloping horse to enactments of mythological episodes and adaptations from literature.

Sequences from films including Kaliya Mardan (1919) and Jamaibabu (1931) play in screens embedded in a celluloid-shaped panel.

Bollywood had dominated the museum's opening event on January 19, but fortunately this is not the case in the museum's contents. The various Indian cinemas all find some mention.

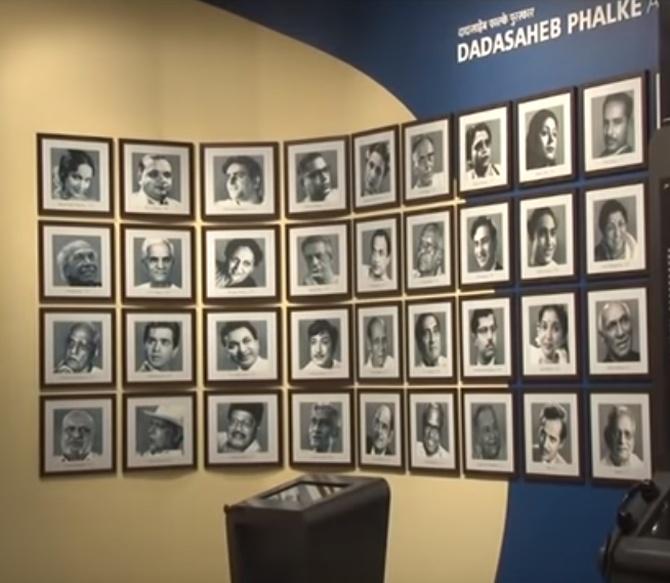

So where Dadasaheb Phalke, as the maker of the first Indian silent feature film, Raja Harishchandra (1913), gets pride of place, the pioneering efforts before him are acknowledged too.

For instance, Hiralal Sen in Kolkata who filmed rallies and advertisements, or Mumbai's H S Bhatavdekar who shot actuality films, and Dadasaheb Torne who made the 22-minute film, Shree Pundalik (1912), which was snubbed for being processed in London.

Lobby cards, vintage posters that are displayed flipbook-style and covers of magazines give a sense of how cinema was marketed and consumed in its early years.

A second large facility, finished in 2018, houses more interactive exhibitions, including where children can create stop-motion animation or control lighting for a shot. The great labour involved in developing a movie -- from an idea into a release -- is deconstructed in one of the halls.

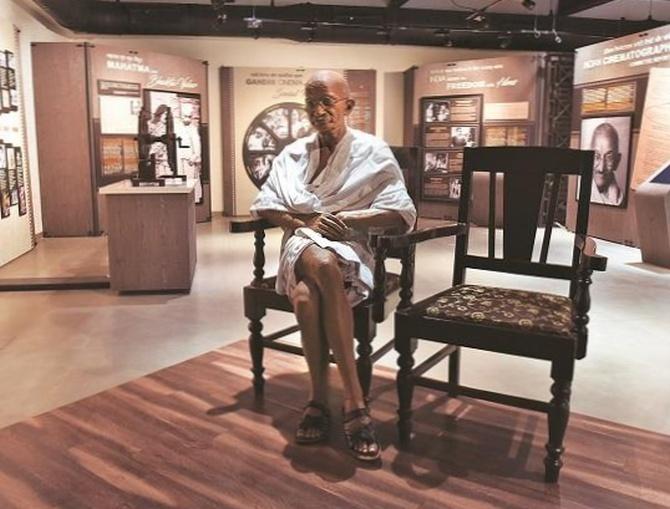

Another offers a social history of interactions between Gandhi, the ruling British Empire and cinema. A lifelike statue of the Mahatma placed here, in front of a screening of 1943's Ram Rajya (the only Indian film he saw), will doubtless appear in scores of selfies.

Throughout the large museum campus, which takes at least three hours to view, few attendants are in sight. Unable to navigate the more hi-tech displays, older visitors presently walk away confused. A dedicated Web site for information on the exhibits and working hours is also needed.

Historically, Mumbai has been the cinema capital of India and for her to have a film museum of this kind was perhaps a natural happening, observes Gangar. The challenge will be to bring in guests from everywhere and walk them through.

Prashant Pathrabe, director general, Films Division, promises film screenings, workshops and tie-ups with educational institutions and museums across India and elsewhere.

Museums today need to be spaces for enlivened storytelling, rather than for lifeless storage. The cinema museum certainly has all the apparatus for this, and could go on to be a worthy fixture in Mumbai darshan tours.

© 2025

© 2025