| « Back to article | Print this article |

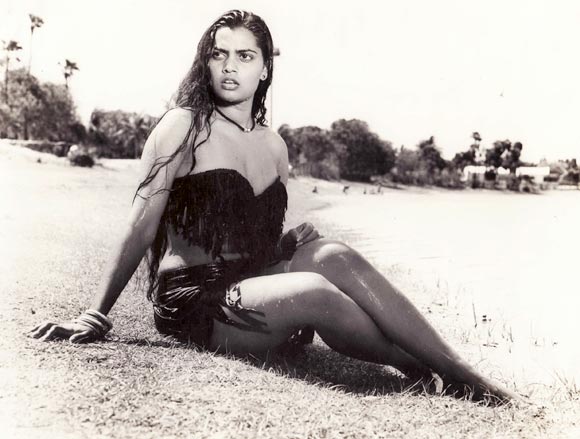

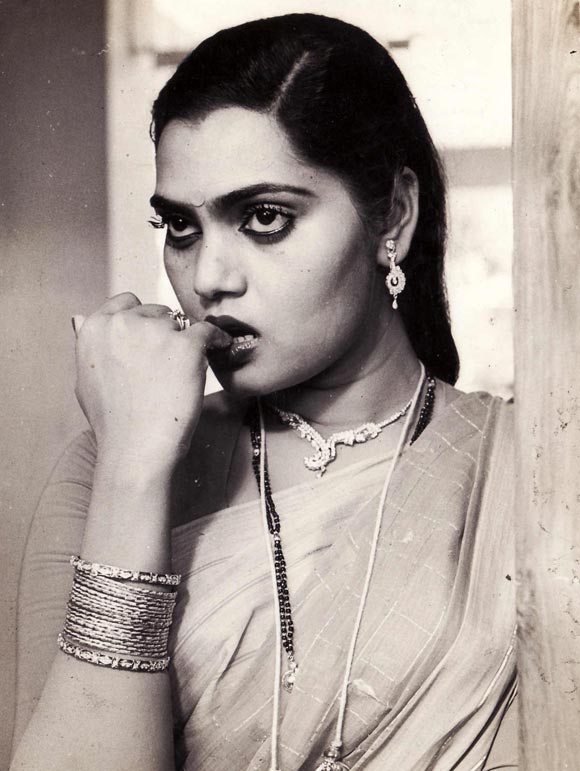

The life of Silk Smitha

Marilyn Monroe had said, 'Being a sex symbol is a heavy load to carry, especially when one is tired, hurt and bewildered.'

Silk Smitha would probably have agreed.

One diva was born in the Los Angeles County Hospital in 1926; the other in Eluru, Andhra Pradesh, in 1960. Their lives might have been supposed to be as different from each other's as chalk and cheese. And yet, had Norma Jeane Baker and Vijayalakshmi actually been able to meet and compare notes, they might have found surprising similarities in their lives, careers, and even deaths.

Whether in Hollywood or Kodambakkam, Marilyn Monroe and Silk Smitha lived lives that were unlike any other. And in their respective spheres of influence, they caused many a flutter, exacted confidences, set hearts aflame and inspired admiration, revulsion and a grudging admiration for how they chose to live.

Vidya Balan pays a tribute to Silk Smitha

With Ekta Kapoor's supposed biopic of Silk Smitha, helmed by Milan Luthria, there is a revival of interest in the sensual southern siren who once symbolised everything erotic in the Indian filmi imagination.

The Dirty Picture focuses on the tremendous success achieved by a small-town girl determined to make it big on her own terms, and the price she had to pay for it.

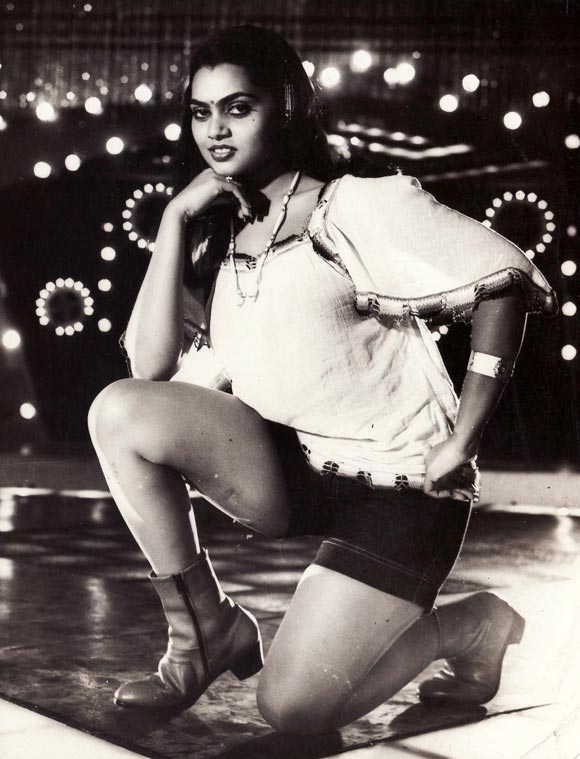

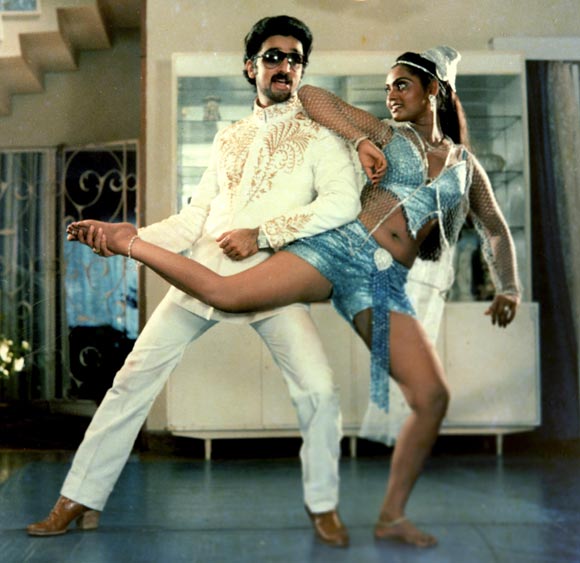

The 1980s was the age of demure heroines and chaste young girls; sex appeal was provided by a host of 'vamps' who dressed as skimpily as the censor board would allow, providing front-benchers plenty of opportunity to whistle.

And yet, "Silk" Smitha was different from them all.

Her childhood

Born in Eluru, a small village in Andhra Pradesh, her real name was Vijayalakshmi and she had dreams of making it big even as a child.

When she was in the fourth standard, the family's finances hit a low. Having already decided on a career in films, she made her way to Kodambakkam, the epicentre of the Tamil film industry, where she began to try out for parts. She lived with her aunt.

Entry into films

Smitha's first job in tinseltown was very far from romantic; she worked as a touch-up girl for an artist. However, she also decided that this wasn't what she wanted to do all her life. She quickly befriended the artist's significant other, who gave her the break she needed.

Her first film was the Malayalam film Inaye Thedi. The "Silk" was tacked on after one of her characters in Vandi Chakkaram, in 1979. It proved to be the break she was looking for, and put her in a different category from the other seductresses who had jumped onto the item-girl bandwagon.

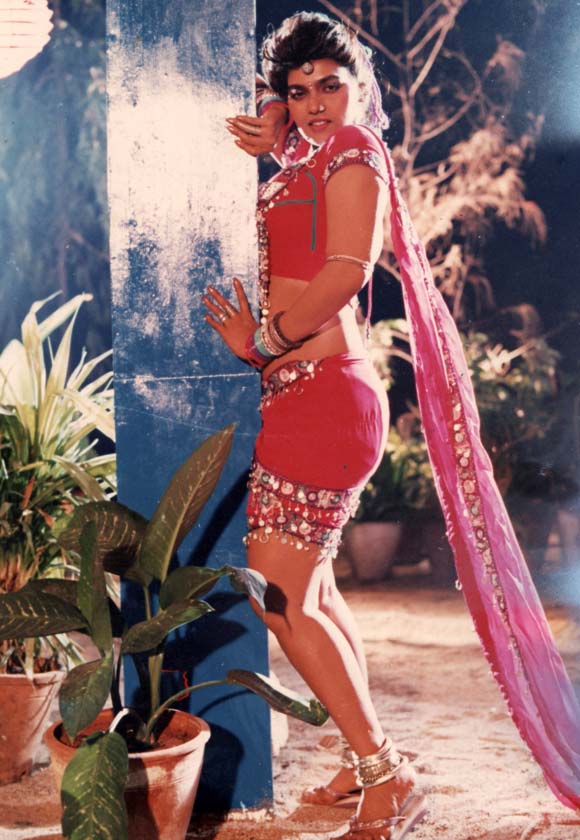

Undoubtedly her curvaceous figure did it, but it was also the tilt of her generous lips, the glint in her heavily made up eyes, the sultry voice and above all, a certain vulnerability that suffused her personality on-screen.

Here was the ultimate diva: someone who delivered the goods with style.

Once, during an interview, she was asked her preferred mode of dress. Smitha replied that it was the sari. The interviewer laughed and said, "But how can you say that?" No one knows what Smitha's reaction to that was.

Road to Stardom

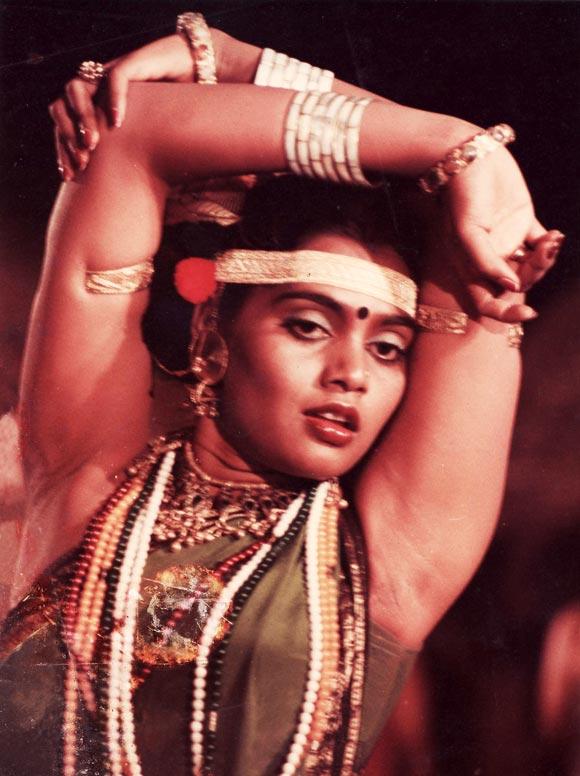

Her overwhelming popularity translated into fame and cash, of course, mostly for single song sequences involving velvet beds, crystal chandeliers and sparkly shorts. Songs like Ponmeni, from Moondram Pirai, and Nethu Raathiri from Sakalakala Vallavan threw her right into the stratosphere, making fans go almost rabid.

She became an icon in the Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam film industries, wearing the rare bikini and going, literally, where others trembled to go. Her innate dress sense made sure that it wasn't just her figure that was showcased but also the clothes.

Memorable Films

It's said that she charged around Rs 50,000 for a single song and shot two or three songs at one go. At one point, she was earning more than the top heroines of the period. Barely a film was made without a sensuous number from her (regardless of how relevant it was to the film).

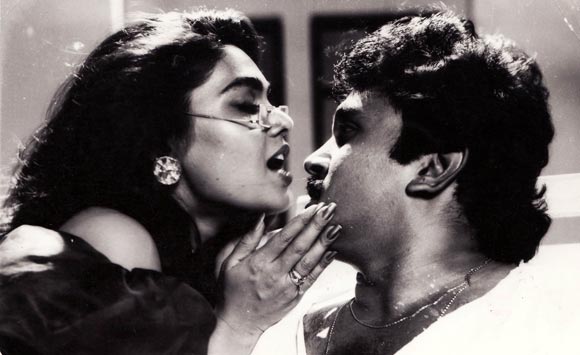

Producers and directors waited in line to get an audience. There was even a movie tailor-made for her: Silk Silk, Silk, which had her playing all three roles. She managed to make her mark in movies such as Yamakinkarudu (1982), Khaidi (1983), Challenge (1984), Layanam (1989) (remade in Hindi as Reshma Ki Jawani) and Adharvam (1989).

It wasn't difficult to see why she was labelled a soft-porn actress; what "roles" she got focused on one and only one aspect. And yet, Smitha could throw you for a loop when she chose and when character-oriented roles actually came her way. Veteran director Bharathiraja cast her as a wife who goes against her fearsome husband in Alaigal Oivathillai. She wore only sarees in the film and displayed not an iota of sexuality. And yet she managed to give other actors a run for their money.

Isolation and Alcoholism

She acted with practically every big star from Kamal Haasan to Rajnikanth and Chiranjeevi in a matter of years. But her private life was more troubled. Love affairs never went anywhere, financial issues almost ruined her productions and she began to suffer from chronic depression.

In the 1990s, the industry began to change as well: heroines were no longer confined to "chaste" roles and did roles that were once the mainstay of the 'vamps'.

Smitha was no longer a front runner in the lists. Not that her appeal grew any less, but the world, it seemed, had moved on. Smitha was seen less and less on-screen; her debts, caused mainly by a live-in boyfriend, sank two films and scuppered a third. Smitha had grown accustomed to a particular lifestyle, certain standards that she expected, but which a dwindling career could not really support.

Suicide

On September 23, 1996, tragedy struck. The southern industry's "Silk" hanged herself after leaving a suicide note in Telugu saying that she'd had enough and was giving up.

Inevitably there was some debate about whether this was a genuine suicide, or whether it had been engineered by those who didn't wish her well. In the end, it was ruled a suicide, the explosive end of a high-profile woman who found herself backed into a corner.

In one of her more memorable movies, Neengalum Herothaan, Silk Smitha plays herself, a dream-girl come to a tiny village for a shooting, being gawked at by every man, from sixteen to sixty, wined and dined by the bigwigs and solicited by everyone. Except for the women, of course, who won't have anything to do with her. Frustrated and saddened, Smitha lashes out at them. "Why does everyone see women like me as a product? Why does no one consider us human beings as well, with emotions and feelings?"

That, you suspect, is a question that haunted her to the end.